Robin Hood is one of the most popular medieval literary figures in modern storytelling. From Disney and the BBC to numerous films, the Robin Hood legend recounts the timeless narrative of the everyman’s hero. A peerless archer and savior of the poor, Robin is a medieval Spartacus. He is a man wronged, righteous, and driven by a moral code higher than the law. But is this medieval adventure story based in reality? Was Robin Hood real?

Myth, Legend, or Reality?

As with so many figures who span myth and history, the origins of Robin Hood are rooted in a period of dynamic political unrest and cultural change. A resistance leader, constantly pursued by the notorious Sheriff of Nottingham, Robin Hood outwitted elites and righteously defended the oppressed.

The legend of Robin Hood swims with historical figures and folk heroes, but the reality of Robin remains contested. The world that gave rise to the hero lies in the tumultuous political landscape of thirteenth-century England.

Robin Hood in the 19th and 20th century

The stories of Robin Hood we know today are the products of 16th to 19th century literary and poetic traditions. They are centuries divorced from the historical era that produced the original outlaws. Robin Hood was rediscovered in the 19th century after the publication of Sir Walter Scott’s enormously popular medieval tale of Ivanhoe. In this era, medieval heroes like Robin Hood were given new life in plays, ballads, and festivals.

By the twentieth century, historians and legal scholars like Maurice Keen and J.C. Holt dug through court and church records, concluding that Robin Hood could have a basis in reality. However, he was likely an early alias for criminals and outlaws.

Robin Hood in Medieval Literature

The earliest literary reference to Robin comes as a name only in William Langland’s eschatological Piers Plowman, written around 1370 CE. The more extensive traditions of Robin Hood begin in the mid-15th century.

The fragmentary story of Robin Hood and the Monk (circa 1450) includes the formulaic traditions of Robin Hood. The story depicts him as religiously devout, morally absolute, loyal to the true King, and resident in the forest. His faithful second Little John is by his side and remains in the later and more extensive text The Gest of Robyn Hode. Both of these texts, written in Middle English, allowed a more popular access by England’s yeoman class, courtiers, or servants in the households of nobles.

You May Like: Was King Arthur Real? Examining the Historical Record

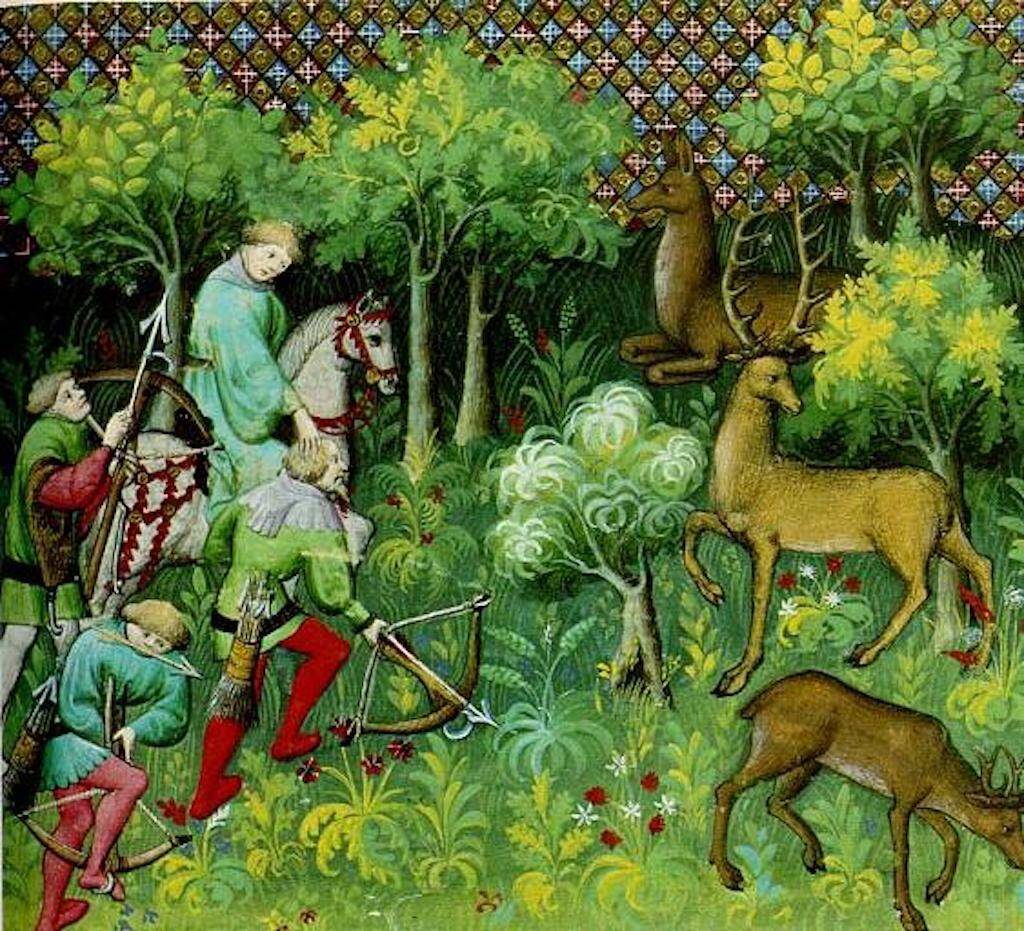

The Gest, a story told by a courtly minstrel, records five of Robin’s famous escapades, including his attack upon the Abbot of St. Mary’s Yorkshire, his gift to the poor but noble knight Richard, and rampant poaching, robbery, murder, and violence. While Robin’s warriors are by his side in these early stories, Maid Marian and Friar Tuck are later additions from the Tudor era.

Robin Hood and Medieval Corruption

Robin Hood does not discriminate in his punishments. Corrupt lawmen, nobles, and especially church officials and clerics are common victims of plunder and murder. Anti-clericalism in the tales speaks not to irreligious behavior but to Robin’s protest of churchmen’s moral corruption.

The stories must have been especially popular after a series of 14th and 15th century calamities, including the Black Death and the Hundred Years’ War. These events laid bare to all the corruption and poor leadership of England’s kings, nobles, and churchmen.

“Fur-Collar Crime”

Outlaw tales feature unlikely heroes engaged in aristocratic codes of behavior that shame the increasingly ill-behaved noble classes. By the 14th century, violent and eager sheriffs, corrupt churchmen, and cash-strapped nobility oppressed England’s peasants.

Medieval wars between France and England and the displacement of nobles as royal court officials by professionalized clerks left English elites status-starved and increasingly cash-strapped. These nobles turned to “fur-collar crimes” – elite kidnappings, highway robberies, protection schemes, judicial corruption, and extortion of peasant communities.

The legends of Robin Hood emerged in the wake of these 14th-century crime waves. The legends are symbolic of the deep, widespread resentment of commoners to aristocratic corruption. Robin famously robs and punished those who violated the law, particularly corrupt nobles and landlords, sheriffs, and mercenary churchmen.

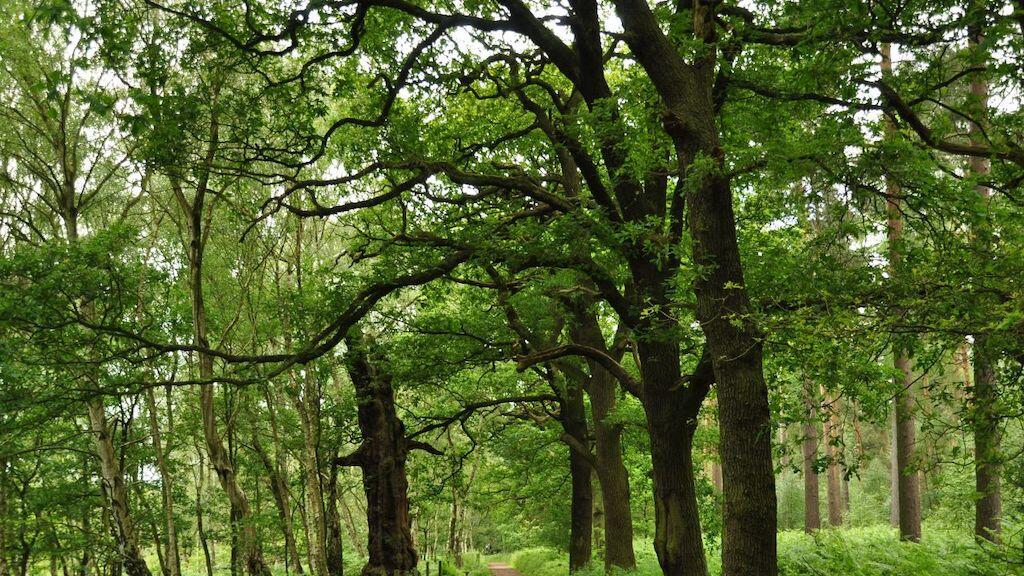

The final critical element in the legend of Robin Hood is the center of his moral universe, the forest. How does the forest become the focal point of Robin Hood’s tales?

Forest Laws of Anglo-Norman and Plantagenet England

After the Norman Invasion of 1066, led by William I the Conqueror (1066-1087), England’s throne and royal court became wholly French in tastes, language, culture, and orientation. The Normans hailed from the small duchy of Normandy in northern France, where royal rights were expansive and laws absolute.

England’s long-established Anglo-Saxon population became disenfranchised practically overnight when this new leadership claimed all land as royal demesne or property. In addition to new land ownership patterns, economic rights became severely curtailed by imported Norman forest laws.

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written in the eleventh century, King William “set aside a vast deer preserve and imposed laws concerning it, so that whoever slew a hart or hind was to be blinded. He forbade the killing of boars, even as the killing of harts, for he loved the tall deer as if he had been their father…The rich complained and the poor lamented….”

Hunting, especially for deer, was strictly forbidden on royal land, as were foraging, gathering, wood collection, and even merely traversing the forest. As a result, Anglo-Saxon peasants lost their traditional means of subsistence, and age-old practices became redefined as crimes against the crown.

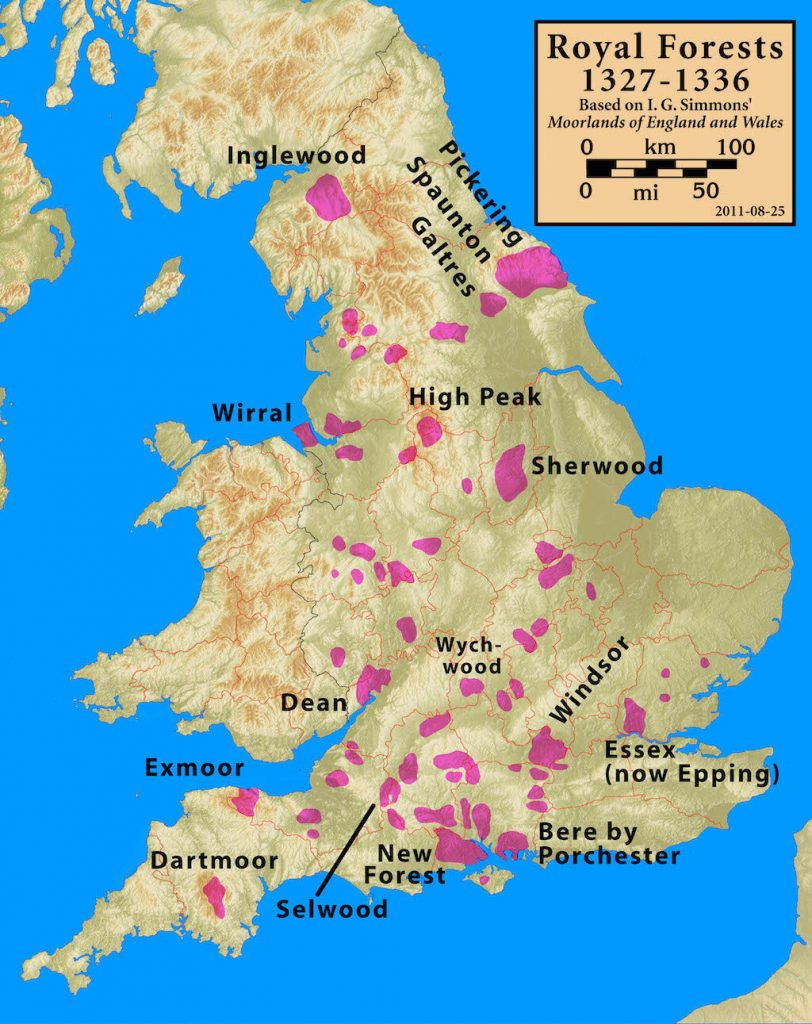

Sherwood Forest, one of several associated with Robin Hood, was a massive woodland that encompassed nearly a quarter of Nottinghamshire’s county. William created approximately 25 royal forests, and by the 13th century, his successors increased that number to 80. The stories of Robin Hood are based in these very forests.

Medieval Forest Law and the Sheriff of Nottingham

Draconian laws protected royal forests, enforced by wardens, verderers, justices-in-eyre, and sheriffs. The Sheriff of Nottingham, Robin’s corrupt and worthless foil, embodies the most hated qualities in medieval English society.

The medieval sheriff collected taxes, conscripted soldiers, enforced the King’s laws to the letter, and maintained harsh discipline in his assigned shire. Punishments, especially for forest crimes, were savage and swift. Scavenging firewood or mast could result in fines or whipping. Killing the King’s deer resulted in blinding, mutilation of hands and ears, and public hanging.

By the 13th century, thirty percent of English land was protected forests, off-limits to all non-elites. As a result, two forests associated with Robin Hood, including Barnsdale Forest of Yorkshire and Sherwood, became protected royal playgrounds for kings like William I, Henry II (1154-1189), and one of England’s most hated kings, John.

Notorious King John (1199-1216) and Magna Carta

Modern Robin Hood traditions place the forest hero in the orbit of the popular and warlike King Richard the Lionheart (1189-1199). Fabulously popular, Richard spent less than ten months of his decade-long reign in England. In his absence, local officials maintained the kingdom and had built up powerful local fiefdoms.

Richard’s malignant brother John succeeded him to the throne and immediately suffered the discontent of English nobles. They resented royal taxes and tributes, mocked John’s incapacity as a warrior. Furthermore, they were used to ruling themselves after decades of absentee kings (Henry II and Richard).

John’s failures as a king culminated in the revolt of the Barons at Runnymeade in 1215. The Magna Carta was the outcome of that revolution. Among its dozens of demands was the restoration of privileged access to the forest, later codified in the 1217 Charter of the Forest.

The peasants, however, remained disenfranchised and abused by kings, sheriffs, and elites. When their revolt finally came in 1381, their demands, including access to the forests, were made with fire and bloodshed.

Earlier Outlaw Legends

Robin Hood’s legend arose in this mix of weak royal authority, overbearing local power, and desperate peasantry. While the earliest written traditions often place him alongside King Edward III (1312-1377), his historical core is unquestionably borne of the earlier Plantagenet era’s disenfranchisements.

But Robin was not the only outlaw of this era. Many others like him – dispossessed, exiled, hunted by the law, and willing to kill for moral justice – rise in the same period.

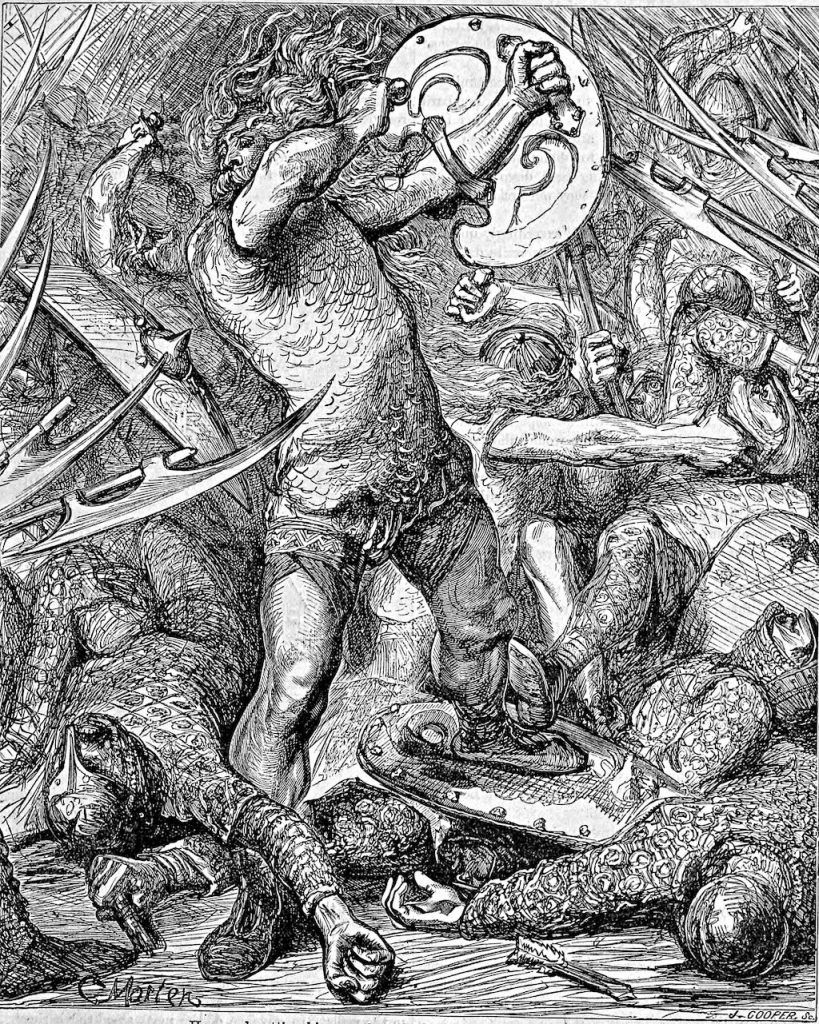

England’s first great outlaw tale was born with William the Conqueror’s invasion. Hereward the Wake was an Anglo-Saxon who lost his family lands in the Norman Conquest. Written in Latin in the mid-12th century, Hereward lives in the fens and forests of southern England with a band of fugitives. He evaded capture through his warrior prowess, his cunning, and many disguises.

You May Also Like: Prester John Legend: Where Was The “Exotic” Land of This Christian King?

For Robin Hood and other outlaws, forests, fens, and natural spaces are uncorrupted spaces, the antidote to royal and noble courts. In the wilds, man’s natural and free state focused on loyalty, fidelity, morality, and honor flourish in an ideal realm.

Was Robin Hood Real?

Robin Hood, according to historians J.C. Holt and most recently, David Crook, could have been rooted in reality. Perhaps a historical figure from Yorkshire in an age contemporary with the Magna Carta. Place names associated with Robin Hood dot that landscape. For instance, St Mary’s Abbey, Yorkshire, Robin Hood’s Well near Barnsdale Forest, his birthplace at Loxley, and a thirteenth-century grave in Kirklees Priory inscribed with the name Robert Early of Huntingdon and the outlaw name of Robin Hood.

Like many medieval heroes who straddle the line of fact and fiction, popular culture during every age reinvents Robin Hood as a moral exemplar and protector of the weak and oppressed.

References:

David Crook, Robin Hood: Legend and Reality (Boydell Press, 2020).

Thomas Hahn, Robin Hood in Popular Culture: Violence, Transgression, and Justice (Boydell and Brewer, 2000).

J. C. Holt, Robin Hood, Third Edition (Thames and Hudson, 2011).

Maurice Keen, Outlaws of Medieval Legend (Routledge, 2001)

Thomas Ohlgren, ed. A Book of Medieval Outlaws: Ten Tales in Modern English (Sutton Publishing, 2000).

Stephen Knight and Thomas Ohlgren, eds., Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales (Medieval Institute Publications, 1997)