A country of approximately 22,000,000 thrown into two-hundred-year isolation. What sounds like a far-flung movie plot line was in fact a harsh reality for the people living in Japan between the 17th and 19th Centuries.

This all came about in 1635, when the Japanese government enacted the Sakoku Edict in an attempt to eliminate foreign influences. What would lead a government to go to such an extreme measure?

Understanding the pathology of three significant Japanese leaders is essential to comprehend the circumstances that led to the Sakoku Edict. These leaders all held power during the Sengoku period, also known as the “warring states” era, which stretched from 1467 to 1615 and was characterized by an almost perpetual civil war in Japan.

The first of these rulers was Oda Nobunaga, a strong daimyo (feudal lord) who, like many other Japanese, was fascinated by Europe.

Oda Nobunaga

The world of the 16th century was rapidly expanding. Trade channels were bustling, Europe had entered the Age of Discovery, and Spanish and Portuguese merchants were busy bringing new commodities into Japan, including clocks, glasses, and, most significantly, weapons. With them, they also brought something much more insidious: Christianity.

Francis Xavier was one of the most notable Christian missionaries who traveled with trading fleets to Japan, seeking to “enlighten” the Japanese. Oda who was not a shogun (military leader, who in these times held more power than the emperor) but still wielded great power was able to offer protection to Christian missionaries like Xavier. Oda never converted to Christianity, so you might wonder why he would go to lengths to protect them.

His interest in religion was solely political. Buddhism was the prominent religion in Japan at the time and he understood that religion had a way of binding people together. If he could use Christianity in the same way that his rivals used Buddhism, then maybe he could rise to the top.

- Where Truth Meets Legend: Was Jimmu the First Emperor of Japan?

- The Story of Utsuro-Bune: a 19th Century Japanese UFO?

By 1582 Oda was so close to doing the seemingly impossible and unifying Japan, a feat that had had not been accomplished in centuries. Just before he succeeded in his goal he was betrayed by his deputy and forced to commit suicide. This is where the second influential Japanese leader, Toyotomi Hideyoshi enters.

Moving closer to Sakoku

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was a follower of Nobunaga and upon his death acted swiftly launching a series of attacks that culminated with him defeating the Samurai general Akechi Mitsuhide. In doing this he completed his predecessor’s task of finally uniting Japan in 1582.

Toyotomi had earned his position, making his way up the ranks from humble origins. He was the son of an ashigaru (foot soldier), working his way to the position of a deputy to a prominent warlord.

It was evident that Toyotomi had understood Oda’s goals for the nation when he assumed the title of “Imperial Regent” (Kanpaku), but he had greater ambitions than his predecessor. After directing a nationwide census, he divided the population into four classes, forbidding people from mixing with those outside their class.

Additionally, he had a growing skepticism about Christian missionaries in Japan as well as the wider influence of Europe. Their Christian message, in his view, posed a challenge to his ability to maintain social and political dominance in Japan. Proving to be an astute leader, he watched as the Europeans (mainly Spanish and Portuguese) traveled in their vast armed military fleets invading and conquering other nations.

The Rise of Anti-Catholic Rhetoric

Toyotomi’s worries turned out to be justified in 1587. Omura Sumitada, a Christian daimyo, was rumored to have sold Japanese slaves abroad. Upon this discovery, Hideyoshi ordered all Christian missionaries to leave the country. Since the Japanese were still conducting business with foreign merchants, the ban wasn’t fully upheld, allowing the missionaries to re-enter under a different guise.

The final straw came in 1596 when Spanish sailors informed him that the Spanish government was in fact using Christian missionaries to win territories around the world. In a fit of rage, he ordered the beheadings of 26 missionaries and 14 Japanese converts.

From this point, any Japanese who had converted to Christianity were questioned about their loyalty to Japan. A mere two years later Toyotomi passed away, but what didn’t die was his anti-European sentiments.

Tokugawa Ieyasu was the third leader to assemble the components of the strategy outlined by his forebears. He wasted no time in passing a number of dramatic directives that sought to permanently isolate Japan from the influence and dominance of other countries.

This culminated with Tokugawa’s grandson Tokugawa Iemitsu passing the infamous Sakoku Edict, often known as the Shogunate, or “closed kingdom,” in 1633 out of fear for the devastation that the spread of the plague, smallpox, and religion would cause. Japan would henceforth exist in splendid isolation, and her customs, social order and way of life would be protected from foreign influence.

Japan Shuts Her Doors

Under this new law the following rules were put in place:

Japanese ships were prohibited from entering foreign seas.

Any Japanese citizen who resided in a foreign land and wished to return would face the death penalty.

If someone was caught fleeing Japan, they would be sentenced to death.

Any ships that arrived at the handful of ports still open to foreign trade underwent extensive searches. The Japanese were primarily searching for missionary stowaways.

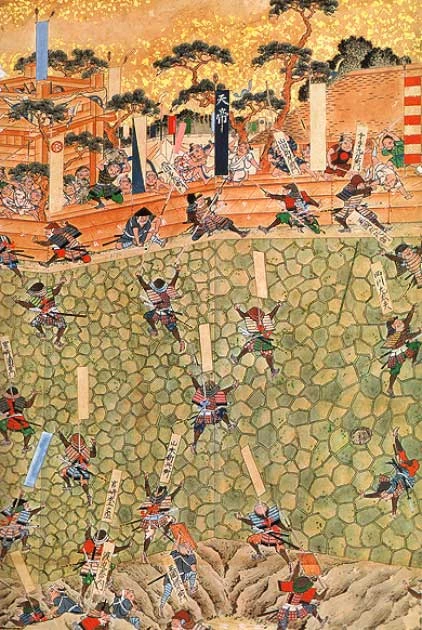

At first this seemed to be working, and peace in the nation lasted a few years. However in 1637 Shibata Katsuie, a ronin (a master-less Samurai) gathered Christian rebels to protest the Sakoku Edict. This was known as the Shimabara Rebellion and was the largest civil conflict in Japan during the Shogunate era. Found guilty of promoting misrule, Katsuie was beheaded, putting an end to the rebellion.

The Sakoku Edict was not the only edict introduced by Ieyasu during his reign. In 1639 he enacted the Exclusion of Portuguese Edict. He felt this necessary as many of the priests who were found to have been smuggled into Japan on Portuguese ships.

What Impact did Sakoku have on Japan?

Prior to the shogunate, Japan engaged in trade with Korea, China, and Europe, utilizing the products that other countries had to offer. However after the Edict was passed the Netherlands was the only country allowed admission when the country closed its doors to the rest of the world.

Allowing the Dutch to continue trading in Japan meant that the nation could continue progressing and evolving. Also the Dutch would sell the Japanese firearms, seen as an important tool for maintaining order by the Shogunate.

The Sakoku Edict came to an abrupt end in 1852 when the US Navy, led by Commodore Mattew Calbraith Perry essentially forced Japan to reopen its market. Japan subsequently signed a Treaty of Peace and Amity with the United States. Finally, the Japanese had could step out and view the world around them.

What effects the Japanese people’s more than 200-year isolation had years later is an intriguing subject. It was immediately apparent once they left the Shogunate that technology around the world had improved significantly, and Japan had lagged behind.

It also became clear that Japanese fashion and culture remained distinctive since they had not been impacted by other Western cultures. Japan certainly preserved its culture in the 200 years of isolation, but it was more akin to a butterfly under glass than a living society.

Who knows what Japan might have become if it had embraced the arrival of foreigners.

Top Image: Tokugawa Iemitsu, who started 200 years of Japan’s isolation after passing the Sakoku Edict. Source: 投稿者がファイル作成 / Public Domain.

By Roisin Everard