In the late 18th century, literary enthusiasts were captivated by the discovery of a trove of manuscripts purportedly written by one of history’s most famous authors, William Shakespeare. The collector responsible for these remarkable finds was Samuel Ireland, a respected writer, and engraver who had amassed an impressive collection of literary artifacts.

However, as the authenticity of his discoveries was called into question, Ireland’s reputation was irreparably damaged, and he became known not as a pioneering collector, but as a master forger. The story of Samuel Ireland and his forgeries is a tragic cautionary tale about the importance of provenance in the study of literature and history.

Who was Samuel Ireland?

Samuel Ireland was an English author and engraver who started out as a weaver in Spitalfields, London. He then moved on to dealing in prints and drawing while devoting his spare time to practicing engraving.

He was soon skilled enough that in 1760 he obtained a medal from the Society of Arts. As he grew in success and wealth he became an avid collector of books, pictures, and curiosities. His collection became large and valuable enough that in 1984 he released “Graphic Illustrations of Hogarth, from Pictures, Drawings, and Scarce Prints in the Author’s Possession”. Despite the title being a bit of a mouthful, it was successful enough that in 1799 he released a second volume.

In particular, Samuel was a massive fan of William Shakespeare. In 1793 he took his son, William Henry, to Stratford-Upon-Avon to examine every part of the town associated with the great playwright. As it turns out this trip would prove to be Ireland’s undoing.

Within a few years, Samuel Ireland would no longer be remembered as a talented artist but as a con man who along with his fool son somehow managed to pull the wool over the eyes of some of Europe’s most respected intellectuals.

An Infamous Collection

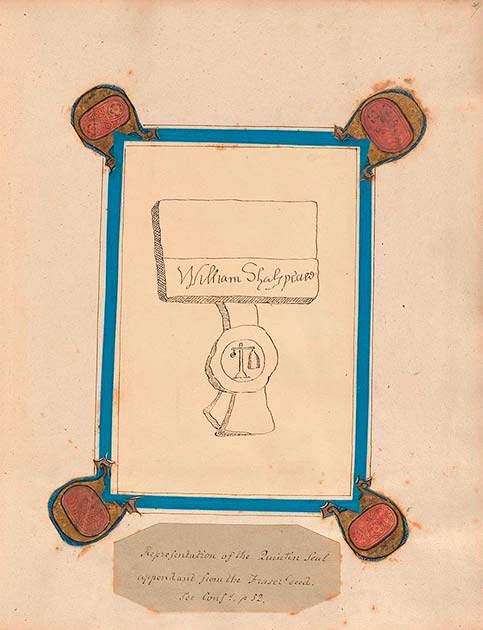

In late 1794 Samuel’s son, William, claimed to have discovered a mortgage deed that had been signed by Shakespeare. He said he had come across the old manuscript in a trunk belonging to a mysterious friend known as “Mr. H”. If this sounds too good to be true it was.

In reality, William Henry had lived his life as an utter disappointment to his father. He had flunked out of school and repeatedly failed in his attempts to become either a famous actor or playwright.

Samuel had hinted repeatedly that the boy wasn’t his and his mother had tried to hide her maternity. She was Samuel’s mistress and had spent Henry’s childhood pretending to be a live-in housekeeper known as Mrs. Freeman.

- Queen Mab and Dreams: Shakespeare’s Inspiration or Another’s?

- The Diary of Jack the Ripper: Inside the Mind of a Madman?

At some point, William became so desperate for his father’s approval that he took it upon himself to forge the Shakespeare document. He had learned from an acquaintance how to simulate the appearance of old writing by using special ink and heated paper and had come across an old copy of Shakespeare’s wobbly signature in one of his father’s books.

He put the two together and created his first forgery. His father was overjoyed and soon began showing it to various experts who all accepted it as genuine. The young man, proud to have pleased his father, then told him that perhaps there were more documents waiting to be found.

Soon he had produced a letter from Queen Elizabeth, a love poem by Shakespeare to his future wife, the “original” manuscript of King Lear and various letters and correspondences said to have been written by Shakespeare. William had finally found something he wasn’t completely useless at.

These were all major finds. While many of Shakespeare’s works were readily available no one had ever managed to write a satisfactory biography of the great playwright.

The problem had always been that besides his works, precious little else relating to Shakespeare had survived. Would-be biographers such as Nicholas Rowe and Edmond Malone had scoured the earth looking for scraps of documents that might be tied to Shakespeare and next to nothing had turned up.

So when Samuel Ireland began letting it be known that his son had come across the holy grail of Shakespeare relics, there was more than a little interest. He began by showing close friends and things quickly escalated from there. In 1794 he invited Sir Frederick Eden (a pioneering social investigator) to inspect the documents. Eden was pleased and announced them to be real.

In the February of 1795, an open invitation was issued to the great and good of the literary world to come and examine Ireland’s new collection. It was a massive success. Various experts visited the house and publicly testified that they believed the documents to be authentic.

What Went Wrong?

Unfortunately for Samuel, his son wasn’t actually a particularly talented forger. Instead, his success was a result of people wanting to believe what they saw. Many of those who came to inspect the forgeries willingly overlooked some of the manuscripts’ shoddiness because they were so delighted to be holding something supposedly written by Shakespeare.

Not everyone was fooled though. One visitor to Samuel’s exhibition noted that a document said to have been written by the Earl of Leicester was dated 1590. This was problematic since the Earl had died in 1588. Samuel and his son put their heads together and decided the document had been “misdated”. They simply tore the date off and re-entered the document into the collection.

Yet the damage was done, at least two scholars, the antiquarian Joseph Riton, and the classicist Richard Poson, had already recognized the document as a fake. Ireland’s removal of the problematic date did him few favors in their eyes.

- The Shakespeare Authorship Question

- Beringer’s Lying Stones: How did a Professor find Fossils of God?

Samuel then made the mistake of neglecting to invite the two greatest Shakespeare scholars of the day, Edmond Malone, and George Stevens, to view his manuscripts. This roused a lot of suspicions.

In the December of 1795, Samuel published his manuscripts, opening them up to scrutiny by experts who had not yet had a chance to view them. Unsurprisingly the manuscripts didn’t stand up to this scrutiny for long.

In no time at all the forgeries were being picked apart. People realized that the signatures on the documents did not resemble, in any way, their counterparts on other already verified documents.

Even worse, Henry had made simple continuity mistakes like mentioning the Globe in a document dated before the famous playhouse had even been built, and using words in the forgeries that hadn’t even existed in Shakespeare’s time. Malone alone released a book of 400 pages that detailed all the ways that Samuel’s collection was obviously fake.

Then on April 2nd Shakespeare’s lost play, Vortigern and Rowena premiered. For anyone curious why they’ve never heard of it, it’s because it was fake. And a bad one at that. The foolish Henry had attempted to write his own play and pass it off as the work of history’s greatest playwright.

The premiere was a disaster. The at-first enthusiastic crowd quickly realized they had been duped and fits of laughter broke out at Henry’s terrible writing. Safe to say the play’s opening night was also its last. Any question as to whether Samuel’s collection was fake had also been answered.

A Reputation Ruined

The saddest part of this story is that even after Malone had exposed the manuscripts as fakes, and even after the play had bombed, Samuel remained convinced his son’s finds were real. When Henry tried to confess to his father, Samuel simply ignored him.

The young man turned to his mother and sisters for help, but Samuel even refused to listen to them. Making things worse, Samuel then set out to slander Malone by writing a book aimed at destroying the expert’s reputation. He was saved at the last minute when Henry released a pamphlet to the public owning up to his fraud.

For many people, this confession wasn’t enough. A lot of experts accused Samuel of being in on his son’s scam. The Ireland family name was left tarnished until well into the 19th century. It was only in 1876 when the British Museum acquired and released Ireland’s letters that it became clear that the poor man had truly been duped by his idiot son.

Top Image: Samuel Ireland believed he had hit upon a treasure trove of documents, including a lost Shakespeare play. Source: vukas / Adobe Stock.