We all know that espionage movies are just that, movies. Nothing in the real world of espionage can live up to them, right?

Well, let’s take a look at “Operation Satanique” and the subsequent sinking of the iconic vessel, the Rainbow Warrior. Surprisingly, few have heard of the time that the French foreign intelligence agency, the DGSE, blew up a Greenpeace vessel in allied territory.

The story has everything: undercover agents, nuclear weapons, high-powered explosives, and daring escapes via submarine. It might sound like something out of a film, but this really happened. And it had very real repercussions.

What was Operation Satanique?

At the crossroads of Cold War tensions and environmental activism, Operation Satanique emerged as a covert operation that would send shockwaves across the world. Crafted by French intelligence operatives, the operation’s aim was to neutralize Greenpeace’s flagship, the Rainbow Warrior, while it was docked in New Zealand.

The choice of name itself, “Operation Satanique,” seems plucked from the pages of a spy thriller, hinting at the intrigue and mystery that surrounded the mission. The operation’s execution lived up to its Robert Ludlum-style name.

The operation began with three DGSE agents, traveling undercover aboard the yacht Ouvea, importing two limpet mines that were to be used for the bombing. These mines were then handed over to two agents posing as newlyweds, Dominique Prieur and Alain Mafar, who were traveling under the aliases “Sophie and Alain Turenge”.

They soon passed on the mines one more time to the demolitions team, divers called Jean Camas (“Jacques Camurier”) and Jean-Luc Kister (“Alain Tonel”). After some intelligence gathering, (which included agents going undercover to infiltrate Greenpeace) the men dived into the waters of Marsden Wharf in Auckland, New Zealand, and attached the two limpet mines to the Rainbow Warrior’s hull.

They set the first mine off at 23.38, waited seven minutes, and then detonated the second. The initial explosion left a hole in the ship’s hull about the size of a car.

After the first explosion, the ship was quickly evacuated. Tragically, some of the crew returned to investigate what had caused the explosion and film the damage. One of these men was Portuguese-Dutch photographer, Fernando Pereira, who headed straight below deck to recover his equipment.

When the second bomb went off at 23.45 poor Fernando was still on board. While the other crew members who had returned managed to safely abandon ship (or were not-so-safely ejected by the explosion’s concussive force), Fernando drowned as the ship’s hull rapidly flooded. The ship itself partially sank four minutes later.

Why Bomb Greenpeace?

This begs the question, why did a branch of the French government think bombing Greenpeace, a civilian organization, was a good idea? The act was more than a little extreme and is now commonly referred to as an act of state terrorism.

- Enormous, Secret and French: What Happened to the Surcouf?

- Wartime Sabotage in a Neutral Country? The Black Tom Explosion

To understand the full context of Operation Satanique, it’s essential to delve into the geopolitical backdrop of the time. The late 1980s saw the world caught in the throes of Cold War tensions, with various nations jostling for supremacy on the global stage. France, in particular, was reasserting its authority and pursuing nuclear ambitions, which included testing in the Pacific.

France had been conducting nuclear weapons tests on the Mururoa Atoll, in the Tuamotu Archipelago of French Polynesia since 1966. However, in 1985 a group of South Pacific islands including Australia, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and a host of others all put their heads together and signed the Treaty of Rarotonga, which made the region a no-go zone for nuclear tests. The French were thrilled.

Greenpeace, on the other hand, had emerged as a prominent voice for environmental protection by this point. Their opposition to nuclear testing and their unapologetic stance against environmental degradation had earned them both admiration and enemies.

They had acquired the Rainbow Warrior in 1977 and had sent it out on various campaigns throughout the 1970s and 80s to protest whaling, seal hunting, nuclear waste dumping, and nuclear weapon testing. Beginning in 1985 it was based in the southern Pacific Ocean, where its crew spent most of their time protesting nuclear testing.

That year the ship heroically relocated 300 Marshall islanders from Rongalep Atoll, which had been polluted by earlier American testing. The ship then traveled to New Zealand where the plan was for it to lead several other yachts in a protest against France’s continued testing in the region.

France was known for having a heavy hand and during other protests ships had been boarded by French commandos after straying too far into restricted waters. This time round Greenpeace planned to monitor the tests by placing protestors on the islands who would monitor the blasts. The French had other ideas.

The Plot Unravels

It should come as no surprise that New Zealand’s government took the bombing extremely seriously, and the ensuing investigation was one of the country’s largest-ever police investigations. The discovery of Operation Satanique and the identity of those responsible unfolded in a series of events that resembled a suspenseful thriller.

Police quickly identified two of the French agents, Captain Dominique Prieur and Commander Alain Mafart, as suspects. They were identified by a local neighborhood watch group and quickly arrested. They were carrying Swiss passports and their real identities were quickly discovered, connecting them to the French government.

The other members of the team fared better. One was identified but fled to Israel before she could be caught. New Zealand police asked their Israeli counterparts to detain her, but she received a mysterious tip-off and fled before she could be extradited.

Those who had smuggled the bombs into New Zealand aboard the Ouvéa fled aboard the same yacht. The Australians, at New Zealand’s behest, caught up with them on Norfolk Island but Australian law stated they couldn’t be held without evidence and so they were released. Handily, a French submarine, the Rubis, came to pick them off, scuttling the Ouvéa while it was at it.

But the damage was done. New Zealand may not have caught them all, but France’s efforts at clean-up operation had done nothing to dissuade the accusations of its guilt. France, an ally of New Zealand initially denied any involvement and condemned the bombing as an act of terror. The French ambassador in Washington went as far as stating, “The French Government does not deal with its opponents in such ways”.

Backlash

What ensued next was a political firestorm. New Zealand, upon realizing who was behind the bombing, began referring to it as “a criminal attack in breach of the international law of state responsibility, committed on New Zealand sovereign territory”. This was less headline-grabbing than a “terrorist attack” but was used to dissuade the French from trying to make excuses with the UN.

Prieur and Mafart, the two agents caught by Auckland police both pleaded guilty to manslaughter and received ten years each. France responded by threatening New Zealand with an economic embargo of New Zealand’s exports to the EU. This would have crippled the country which was reliant on trade with the UK It wasn’t a good look for France.

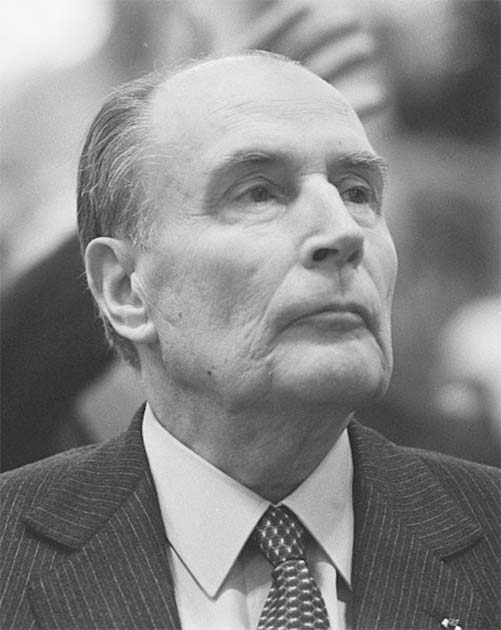

France then launched its own investigation into the bombing. It found that all the agents were innocent and had only been spying on Greenpeace. Someone else must have blown up the ship. These findings were contradicted by both The Times and Le Monde, which claimed President Mitterand himself had approved the bombing. This resulted in the resignation of Defense Minister Charles Hernu and the firing of the head of the DGSE, Pierre Lacoste.

Finally, on 22 September, realizing the cat was well and truly out of the bag, French Prime Minister Laurent Fabius admitted there had in fact been a plot. He read a 200-word statement that acknowledged France’s guilt and the subsequent cover-up.

France ended up paying millions in compensation to Greenpeace, New Zealand, and the family of the dead filmmaker. But it was a case of too little too late. New Zealand shifted its foreign policy, drawing away from France and the US (who it felt had been unsupportive) and growing closer to other South Pacific nations, especially Australia.

While France and New Zealand are still allies today, the topic of Operation Satanique has a tendency to crop up every few years. As recently as 2016 French Prime Minister Manual Valls was forced to eat humble pie during a visit to New Zealand, referring to the incident as a “serious error”.

So, yeah. France bombed Greenpeace on New Zealand soil. A story so strange it has to be (and is) true. This tale of espionage, activism, and environmental consciousness reminds us that even in the face of covert machinations, the truth has a way of surfacing.

The aftermath of this incident redefined international relations bolstered the power of collective voices and underscored the importance of transparency and accountability in the modern world. But the incident also served as a reminder of how far powerful nations will go to pursue their own agenda.

For many the most shocking part isn’t just that France bombed one of its allies. It’s that it had the gall to threaten economic sanctions if it didn’t get its own way afterwards.

Top Image: The Rainbow Warrior was sunk by explosive charges set by the French Government in harbor in New Zealand. Source: Raymond L. Blazevic / CC BY 2.0.