Disney is a cultural behemoth, a cornerstone of western society. One of the most successful businesses of all time, it built it all on groundbreaking animation, storytelling, and fairy tales.

Some of what Disney achieved in its golden age in the mid to late 20th century is staggering, not just for the artistry but on a technical level, too. But one of its greatest technical achievements, realized over half a century ago, is something they can no longer produce today. There is a lost technology at the heart of the House of Mouse.

Known as the “Sodium Vapor Process” or the “yellow screen” technique, this was a revolutionary special effects process. Developed in the 1950s, it is most famously associated with Disney’s production of Mary Poppins in 1964.

In the scenes using the process, Julie Andrews and Dick van Dyck dance in real time with animated characters and a fully animated background. This would seem to be nothing strange to a modern audience used to CGI and green screen effects, but the pair are integrated into the scene with a realism that modern computer techniques struggle to match, if indeed they can match them at all.

The actors are able to dance rapidly across the scene, their arms and legs blurred with motion but without a hint of the matte lines which typically plague such overlays. Julie Andrews wears a sheer material over her hat through which the background can be clearly seen, a near impossibility for modern techniques.

The secret of the sodium vapor process is a magical prism, of which only three examples were built. The prism removed not green or blue light as is typical today, but a very narrow wavelength of yellow light.

And nobody knows where these three prisms are today.

The Sodium Vapor Process Explained

It was Wadsworth E Pohl who fully realized the potential of the sodium vapor process for Disney, but in truth he was building on existing technology. Developed first in the British film industry in the late 1950s, the sodium vapor process was an advancement in the chroma key technique.

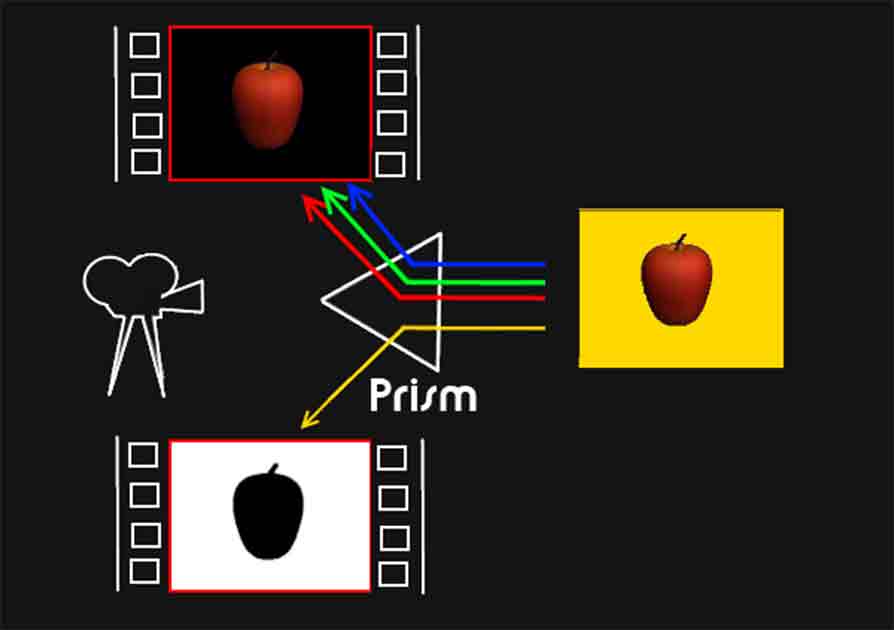

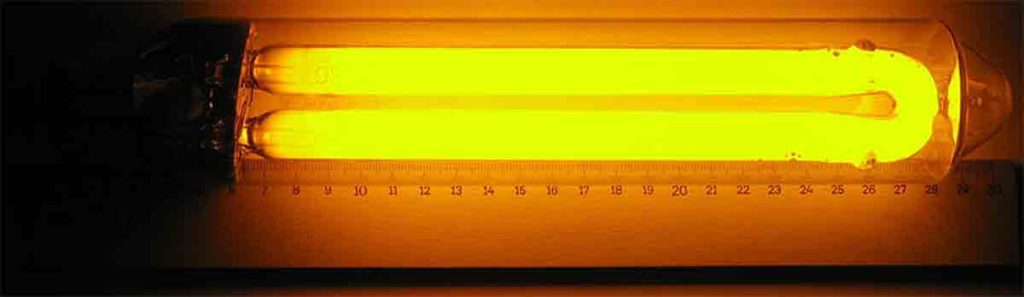

The specially designed prism was placed inside a camera that could simultaneously record actors in front of a background screen onto two separate pieces of film at once. one for the actors and one for the background. The background was lit by a battery of very special sodium vapor lamps, and then technique leveraged an unusual aspect of sodium light: the light that comes from sodium lamps is emitted in a single, extremely narrow band of wavelengths.

The background screen, lit with the narrow-band sodium vapor lights which emitted this very specific yellow wavelength, would be captured by the camera along with the foreground performance from the physical actors. The custom-made prism within the camera could then perfectly separate the yellow background from the actors, allowing for an extremely clean removal of the background for only a vanishingly small section of the spectrum of visible light.

Still impressive today, the sodium vapor process was a staggering leap forward in the realm of visual effects at the time. Before its invention, combining live-action and animation was a tedious and often unconvincing endeavor.

The technique was used to stunning effect in Disney’s Mary Poppins where it allowed characters to dance with animated penguins, fly kites in cartoon skies, and travel into paintings. The sharpness and clarity with which live-action and animated elements were combined were unparalleled at the time and opened up new storytelling possibilities.

Other films, such as Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds a year earlier in 1963 also utilized the sodium vapor process to achieve effects that were groundbreaking. The process enabled filmmakers to composite more intricate and dynamic interactions between actors and special effects, enhancing the believability of the scenes and pushing the boundaries of cinematic storytelling.

So Where is it Today?

So if this process is so astounding, why is it not still in use today? Well, there are a lot of good reasons for this. Firstly, the sodium vapor process, while innovative for its time, has been largely supplanted by digital compositing and CGI techniques.

Modern CGI offers a level of detail, flexibility, and efficiency that surpasses the capabilities of the sodium vapor process. Digital artists can create entire worlds, detailed characters, and complex interactions in a virtual space, allowing for effects that are limited only by imagination.

Moreover, digital compositing has removed the need for physical screens and specialized lighting, making the integration of live-action and animation more seamless and versatile. Modern green screen techniques may be more labor intensive than the sodium vapor process for some applications, and there are certainly some things which cannot be achieved by modern techniques, but the end result can often be better.

Secondly, there is a prohibitive cost to manufacturing the prisms necessary to separate the sodium light, and we do not even know everything about how Disney made their three prisms. Aspects of their design remain a closely guarded secret, and we can only guess as to how the effects on vintage movies from half a century ago were achieved with such beauty.

Attempts are being made to recreate the prisms but by this point they are a curiosity from a superseded technology. They would certainly have an application in modern filmmaking were they to be brought back, but with everything that can be realized by modern green screens it would be niche at best.

- The Conqueror: Did US Bombs Kill US Movie Stars and Their Film Crew?

- The Viking Sunstone: Medieval Ingenuity and Maritime Navigation

In this rush to build digital worlds something has been lost though. The tactile authenticity and the inherent charm of the sodium vapor process and similar practical effects hold a nostalgic value. They required a level of ingenuity and physical craftsmanship that is less visible in the modern age.

Additionally, because these processes were physically crafted, they often imparted a unique visual character to films that can be less prevalent in the sometimes overly polished look of CGI. Much effort is expended to impart “authenticity” into CGI creations, something the antique analog process can achieve with comparative ease.

The Lost Prisms

As for the original prisms themselves, they have been lost to time, perhaps languishing in some crate in a Hollywood backlot, perhaps sitting unrecognized as a paperweight on some exec’s desk. Most likely one of more have been destroyed, but there is still hope that they may be found one day.

These prisms, custom-made and extremely precise, were key to the process’s ability to separate the sodium vapor light from the actors so effectively. Without these prisms, replicating the exact sodium vapor process as it was used in films like Mary Poppins is impossible, marking the end of an era in special effects technology.

The loss of these prisms is a poignant reminder of the transient nature of technology and the importance of preserving historical artifacts of cinematic history. While the sodium vapor process may no longer be used, its legacy lives on in the advancements it spurred in visual effects technology.

It stands as a testament to a time when the magic of movies relied on the ingenuity of inventors and the skill of artists, a bridge between the practical effects of the past and the digital wizardry of the present.

Mary Poppins was considered to be the finest thing Walt Disney ever achieved in his lifetime. Pohl, along with the two Disney animators and executives Ub Iwerks and Petro Vlahos, received Oscars for the film. As well they might, for with the sodium vapor process they had achieved something nobody had before, something nobody can today.

Top Image: Disney was able to create entirely new effects with a much greater sophistication using the sodium vapor process and their proprietary prisms. Source: Disney Trailer Screenshot / Public Domain.

By HM Editorial Staff