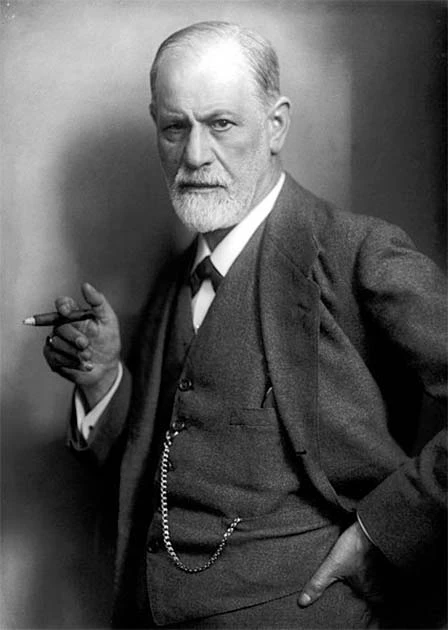

Sigmund Freud, renowned for his groundbreaking contributions to psychology, was a complex and multifaceted man. He was also possessed of some strange past-times, and once delved into an unconventional pursuit that might leave many scratching their heads: dissecting eels.

Beyond the realms of the human mind, Freud found fascination in the elusive secrets of eel reproduction. This peculiar chapter in Freud’s scientific endeavors raises the obvious question: what prompted the father of psychoanalysis to dedicate his time to unraveling the mysteries hidden within the aquatic world?

The answer is he, along with many other naturalists, was trying to work out what the heck was going on with eels’ apparent lack of genitalia.

The Hunt for Eel Testicles

In 1873, when he was just 17 years old, Freud began studying at the University of Vienna. Originally, he planned on studying law but found himself gravitating towards medicine.

Over the years he took up many pursuits, studying philosophy, physiology, and zoology. It was the latter, under his Darwinist professor, Carl Claus, which led him to spend a month chopping up eels.

In March 1876 Claus sent Freud to his zoological research station in Trieste, Italy. While there he had one simple mission- dissecting hundreds of eels until he came across an eel with testicles.

It took him four weeks but after dissecting around 400 eels he finally found what he was looking for, buried deep within a carcass. And what he found was far more important than a simple curiosity.

This might sound like some weird academic hazing ritual, but it wasn’t. Freud was genuinely helping his professor carry out important research in an attempt to answer one of biology’s oldest questions.

So why were Freud and his master obsessed with eel testicles? Because, somewhat shockingly, no eel had ever been found with male genitals.

- Corpse Medicine: The Surprising History of Human Fat Treatments

- Weird Science! What was James Graham Doing in His Electric Sex Temple?

Europeans had been dining on eels for millennia and there was not one recorded instance of an eel being caught that showed any signs of having reproductive organs. This meant the humble eel threatened everything science thought they knew about reproduction and reproductive theory. If eels didn’t have boy and girl parts, how exactly did they reproduce?

This was a big problem. Ever since the times of ancient Greece scientists have had a rough grasp of how reproduction worked in most animals. The Greeks recognized that all animals came from some kind of reproduction and that for most of them, the mechanism was sex between a male and a female who had different organs.

They didn’t fully understand the nuts and bolts of how sex worked and had some pretty wild theories, but the key was that there were male and female animals. But all theories have holes, and it was soon discovered some animals didn’t seem to have sex or the equipment required for it.

Flies, worms, and sponges for example, had either never been seen having sex or had no discernibly different male or female varieties. The most confusing of these were catadromous eels. How did these animals have babies?

It was the great thinker Aristotle who first came up with the solution. He deduced that animals like eels that lacked genitalia reproduced non-sexually. In his work De generatione animalium he explained how all animals contained pneuma or the “breath of life”.

He theorized that when this pneuma interacted with “elemental matter” (the world’s very building blocks) life was created spontaneously. Different types of matter created different animals, for example flies from dung, barnacles from the sides of boats, and eels from mud and wet earth.

This spontaneous generation theory lasted for a surprisingly long time, although different philosophers came up with slightly different variations. Pliny the Elder, for example, explained that eels reproduced by rubbing themselves against rocks, their shed skin particles then growing into new baby eels. Greco-Roman poet Oppian, on the other hand, explained that eels made a foamy secretion that mixed with sand to create their young.

Over the next thousand years, Aristotle’s theory was believed to be the most plausible explanation. There was the occasional rebel, like Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) who dared to challenge Aristotle’s view, but they were all ignored and in truth most of their theories were even more outlandish.

Hildegard, who refused to believe God would have singled out eels to be special and explained that they reproduced by spitting their eggs and semen onto rocks. The male would then wrap himself around the rock to protect it while the female “blew air” into the eggs until they hatched.

By the 13th century, when the Aristotelian corpus was translated into Latin, the theory had become scientific fact. This was despite the fact there was literal evidence it was wrong. Fishermen had reported seeing eels being born alive, meaning they had to be the product of sexual reproduction.

It was only during the Renaissance that the theory began to fall out of favor. Throughout the 16th century, various experimentalists dedicated themselves to disproving Aristotle. Using newly invented microscopes they studied the life cycles of flies to prove that the insects reproduce sexually.

By the 18th century, it was widely accepted that Aristotle had pretty much gotten it wrong. However, eels continued to be a fly in the ointment. No one could explain how they reproduced.

- John Hunter: Syphilis, Hubris, and the Great Misbegotten Experiment

- The Cave of the Magdeburg Unicorn: How to get Fossils Wrong

In the early 18th century, a doctor from Comacchio found evidence of female ovaries in an eel but no one could find their male counterpart. This led some of the time’s leading naturalists to begrudgingly admit that perhaps eels did reproduce asexually, however far-fetched it sounded.

The Truth About Eel Sex

So, Freud’s finding was actually a major breakthrough. His evidence of male testes in eels, combined with the previous Italian discovery proved that eels did reproduce sexually.

However, this raised another troubling question. Why had it taken over 2000 years for someone to prove that eels weren’t magical creatures that made their young asexually?

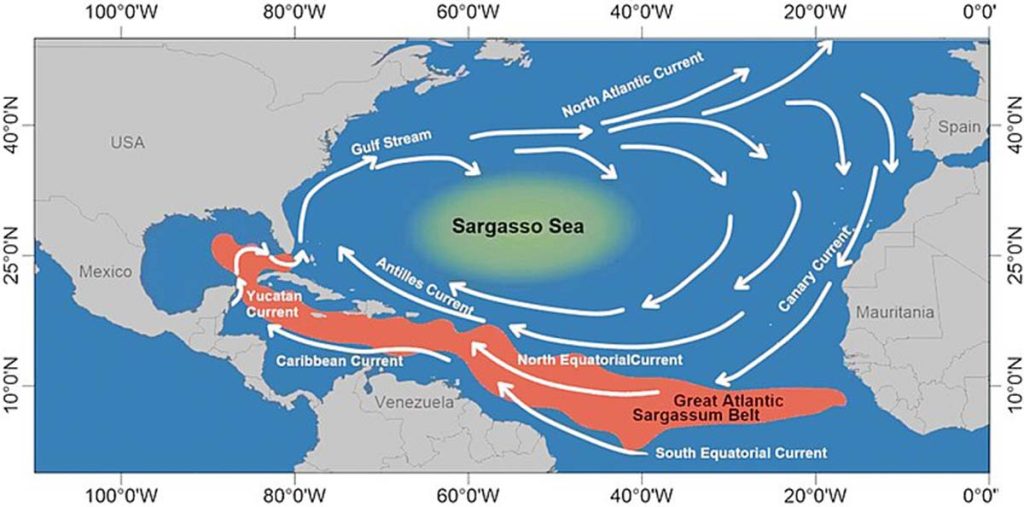

That answer came in the early 20th century courtesy of Danish scientist, Johannes Schmidt. It had long been known that eels migrate and leave European waters for extended periods of time. Schmidt found that while traveling thousands of miles from freshwater habitats to the Sargasso Sea for reproduction male eels underwent an amazing transformation.

It turned out that male eels only grow their male parts while journeying to the Sargasso Sea and won’t grow them anywhere else. Unless you caught an eel there, you’d never know they had genitals at all.

Further research in the latter half of the 20th century refined the understanding of the eel’s life cycle. Scientists uncovered the specific mechanisms by which eels reproduce in the Sargasso Sea, involving the release of eggs and sperm, fertilization, and the subsequent development of larvae.

Technological advancements, such as tagging and tracking devices, enabled researchers to monitor the migration patterns of eels, corroborating and expanding upon Schmidt’s pioneering work.

The Age of Scientific Discovery

Sigmund Freud’s four-week quest to uncover eel testicles was a chapter in the broader narrative of scientific inquiry during the late 19th century. The mystery of eel reproduction, rooted in the absence of observable reproductive organs, spurred curiosity and speculation.

Over time, dedicated researchers like Johannes Schmidt dispelled the mystery, revealing the intricacies of the eel’s migration and life cycle. Freud’s unconventional foray into the world of eels, though not immediately fruitful, contributed to the collective pursuit of knowledge that eventually unlocked the secrets hidden beneath the scales of these aquatic creatures.

Top Image: Some aspects of eel reproduction remain a mystery to this day, despite Freud’s breakthrough. Source: Artemas Ward / Public Domain.