Walking onto the surreal shores of Mono Lake is like entering a fantasy world dominated by spiring tufa towers. This natural body of water near the Nevada border in Central California lies within the Mono-Inyo volcanic system next to the Long Valley caldera. Although people sometimes refer to California’s ancient saline lake as “America’s Dead Sea,” it is far from dead. Instead, processes underground, coupled with a brimming ecosystem and limestone formations, are Mono Lake’s intriguing little mysteries.

How Did Mono Lake Form?

One to three million years ago, while the Pacific and Continental plates were colliding, the earth’s crust stretched and cracked at the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada mountains. The thin crust resulted in numerous volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and subsidence (sinkage of land) at least 2.5 to 3 million years ago. Subsequently, the Mono Basin, a drainage zone surrounded by mountains, formed.

Mono Lake lies within Mono Basin and is a remnant of a much larger prehistoric body of water called Lake Russell (named after a geologist). The vast inland sea filled the whole basin and extended into Nevada (USGS). Lake sediments confirm that Mono Lake is older than the Long Valley eruption, which took place 760,000 years ago. Therefore, the lake is one of the oldest in North America.

Glaciers, many of which no longer exist, fed the basin with runoff during much wetter times. As the warming climate melted the glaciers after the last ice age, water levels fell, and much of the basin dried up. Israel C. Russell was a geologist who provided one of the most thorough assessments of Mono Basin and Lake. In the late 19th century, he indicated in Quaternary history of Mono Valley, California, that there were nine small glaciers in the nearby mountains draining into Mono Lake. Today, there are four main ones: Conness, Dana, Kuna, and Koip (Shuler).

Description of Mono Lake

Mono Lake occupies 44,479 acres. Its length is 13 miles, while its width is about 9 miles. Although its depth was around 900 feet during the Ice Age, it currently averages only 56 feet with the deepest point at 160 feet.

Because Mono Lake has no drainage outlet, salt accumulates in its waters. One gallon of water contains approximately three-quarters of a pound of salt (Hill). The high salinity makes the lake extremely alkaline and two to three times saltier than the ocean. For most species, it is an inhospitable place. Additionally, humans cannot drink the water.

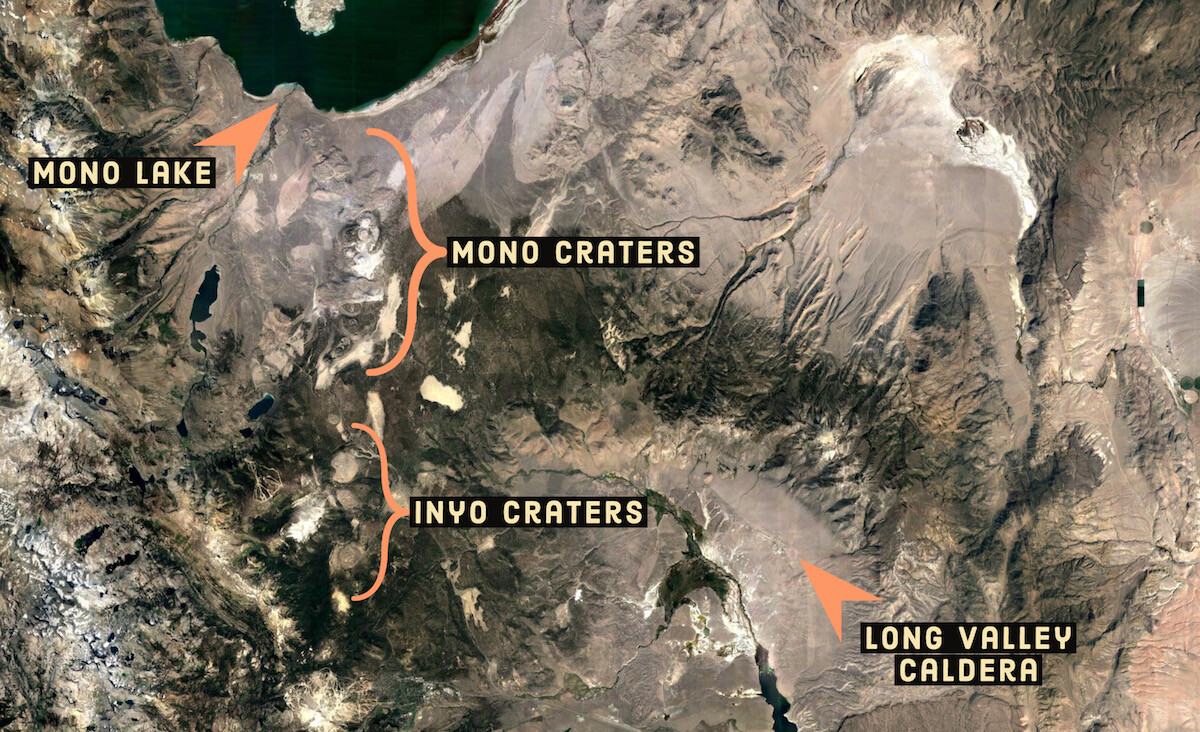

The area running between Mono Lake to the Long Valley caldera (see photo) is still alive with active volcanism. The Mono Craters, south of the lake, is a series of volcanoes that fall into the same system as Long Valley. Mono Lake last erupted explosively about 300 years ago, which formed Paoha island inside the lake. About 2,000 years ago, another eruption created Negit island, the smaller of the two main islands. Interestingly, the magma under Mono Lake is not a part of the magma reservoir that supplies the Mono Craters (Hildreth).

As a result of the active volcanism, many thermal springs flow up from the lakebed. Besides glacial and snowpack runoff, hot (and a few cold) springs contribute to the water level, as does the occasional rainfall. Drought, evaporation, groundwater loss, and human diversions are the only ways water can escape Mono Lake.

Tufa Towers

The most visually striking aspect of Mono Lake is its tufa structures that decorate the arid shores and punctuate areas in the water. Tufa is simply limestone. For the ordinary visitor to this inland sea, the uniqueness and creation of these alien structures are mysterious. They appear somewhat like stalagmites that form in moist caves, except much rougher and porous like a coral reef. Formed from underground springs, tufa towers in and around the lake stand as tall as 20 feet.

All the tufa spires were once under water. However, many formations now rest on Mono’s shores due to lower water levels. Hundreds of feet above Mono Lake, one can still find Ice Age tufa structures that testify to the lake’s former huge size (Mono Lake Committee).

Chemically, Mono Lake’s tufa towers form when thermal springs bring up calcium that mixes with carbonates in the water. Calcium carbonate, also known as limestone, is the result. As the water percolates upward, the lime grows up around the springs over the centuries. Tufa towers are still rising a few millimeters per year under the water of Mono Lake today.

Geobiologist Jack Farmer found tiny fossils of organisms that became trapped within the limestones as carbonates solidified around the springs. Cyanobacteria, casings of fly larvae, and what appear to be algae were among them. (NASA).

California’s “Dead” Sea

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Israel C. Russell”]It is in truth a Dead Sea, but without the mysterious charm that history, tradition, and religion impart to the similar sea in Palestine.[/blockquote]

Around 1861, Mark Twain visited Mono Lake. He later wrote, “Mono Lake lies in a lifeless, treeless, hideous desert, eight thousand feet above the level of the sea. . . This solemn, silent, sail-less sea—this lonely tenant of the loneliest spot on earth—is little graced with the picturesque.” He didn’t appear to be impressed.

Although it bears similarities to the Dead Sea due to its high salinity, Mono Lake has an ecosystem far from dead. True, its harsh alkali waters result in few living things in the water; there are no fish or reptiles. However, an abundance of algae serves as the foundation for a thriving, albeit limited, ecology at the lake.

Mono Lake’s Ecosystem

“Sea Monkeys” – Artemis monica

Remember when comic book ads sold the mysterious Sea Monkeys that grew into brine shrimp when you put them in the water at home? Well, Mono Lake has trillions (estimated) of its very own endemic species called Artemis monica. They grow to almost half an inch and breathe through feathery fibers on their legs. Because Artemis can live in extremely salty conditions, they occupy a niche without many predators and live in abundance. The shrimp feed on algae and are present mostly in the warmer months. During the winter, they form cysts that remain on the bottom of the lake and become active the following summer.

Incredible Scuba Diving Flies – Ephydra hians

Like the brine shrimp, masses of alkali flies inhabit the lake and feast on algae and cyanobacteria. However, these are not typical house flies; these are scuba diving flies that trap air around the waxy hairs on their bodies. The air bubbles allow them to breathe under water, where they will spend two of their three life stages. Adult female flies walk down into the water and lay eggs that hatch larvae. The larvae become pupae. After one to three weeks, an adult fly will emerge and live on the shore, where it will feed and breed until it is time to lay eggs in the water again. During the summer, thick blankets of flies cover the shores of the lake.

Birds on the Pacific Flyway

Mono Lake is in the Pacific Flyway migration zone. Consequently, around two million birds use the site as a feeding and nesting stopover on their way to their final destinations during the summer and fall. Because of the vast quantities of brine shrimp and alkali flies, the lake is an all-you-can-eat buffet. As such, the feathery travelers can fatten up before their long journeys as far as South America or Alaska.

More than 100 species of birds visit the lake, including about 35 varieties of shorebirds. The most abundant are gulls, grebes, and Phalaropes. The Western Hemisphere Shorebird Network has recognized Mono Lake as a critical bird habitat. In fact, it is the second-largest rookery for California Gulls (Salt Lake is the biggest), which nest mostly on Negit island in the lake.

Mono Lake’s Islands

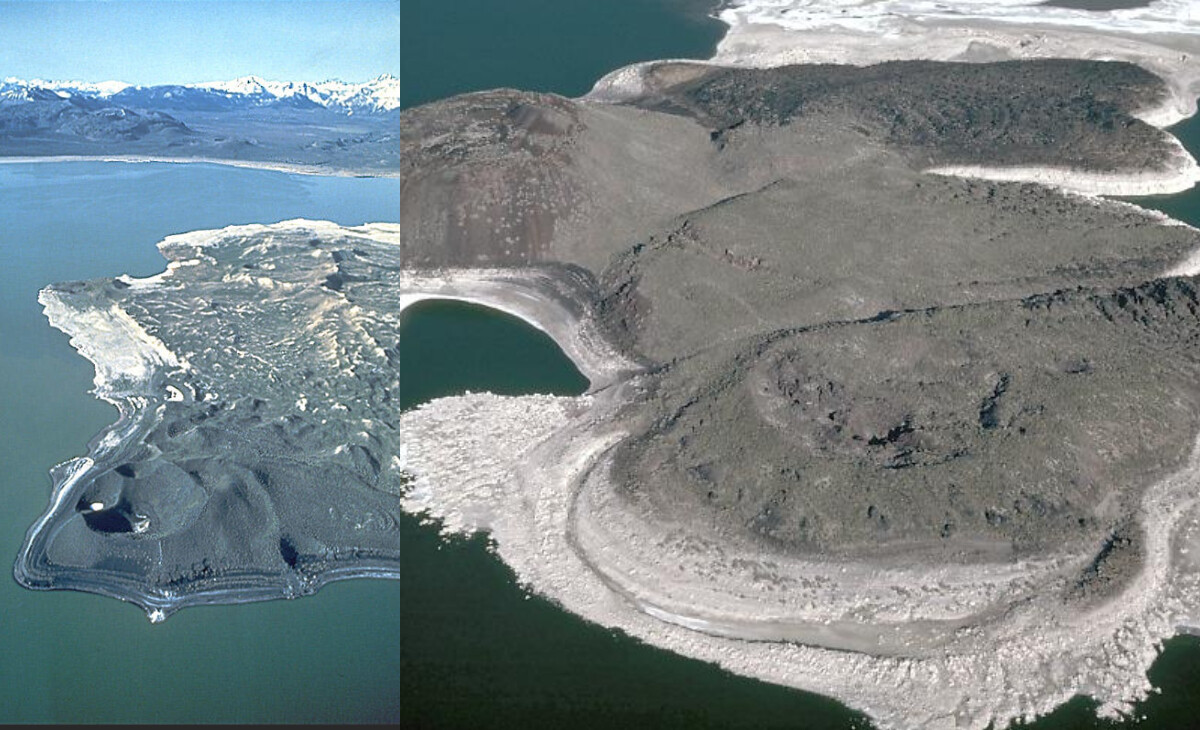

Negit and Paoha are Mono Lake’s two main islands. Israel C. Russell, noted above, named both of them. Negit is the Kutzadika’a Northern Paiute word for “goose” or “gull.” Russell named Paoha after the wispy spirits that the Native Americans believed rose out of the steam at the hot springs on the island.

Most of Paoha island formed when magma pushed up the lakebed. Therefore, much of its surface consists of lake sediment. However, recent lava flows erupted at the northeast corner and eastern point between 1720-1850. One of the volcano craters possesses a small lake.

Negit is the smaller of the two major islands. It formed between roughly 2,000 and 200 years ago when three separate vents erupted lava flows that merged into one landmass.

Northern Paiute Native Americans

Before European settlers expanded into the Mono Basin, a group of Native Americans from the Northern Paiute tribe lived there. Their name, Kuzedika or Kutzadika’a, means “eaters of the brine fly pupae.” They called this food source kutsavi.

Roughly 200 Kutzadika’a depended on Mono Lake. They moved around during the year hunting and gathering a variety of foods. During the summer, they headed to Mono Lake to collect one of their main staples, alkali fly larvae, and pupae. In William H. Brewer’s journal Up and down California in 1860-1864, he described how the Kutzadika’a processed the insects:

“The worms [pupae] are dried in the sun, the shell rubbed off, when a yellowish kernel remains, like a small yellow grain of rice. This is oily, very nutritious, and not unpleasant to the taste, and under the name of koo-chah-bee forms a very important article of food. The Indians gave me some; it does not taste bad, and if one were ignorant of its origin, it would make fine soup. Gulls, ducks, snipe, frogs, and Indians fatten on it.”

Changing Tides

As the years passed and more humans moved to Eastern California, many things changed for the lake and the Native Americans that relied on it. In 1941, Los Angeles diverted the water running into Mono Lake. Consequently, the water level dropped detrimentally low, and salt levels doubled. Conservation efforts and lawsuits reversed most of the diversions, but damage to the ecosystem had already occurred. Today, the water level is not back to where it should be. However, indicators of a healthy lake are improving as the water continues to rise.

For the Kutzadika’a people, the mining towns and agriculture that popped up around the Mono Basin affected their food sources and accessible lands. Although they try to maintain a traditional lifestyle, many of them have had to find jobs. Additionally, most of them stopped collecting flies in 1950 due to the stressed ecosystem.

A Vibrant Inland Sea

Mono Lake, as one of the oldest lakes in North America, is unique. It maintains an ancient geological and microbial footprint in its lakebed, tufa, and surrounding hills. Although it has a simple ecosystem with little diversity, the sheer volume of its dominant species is striking. For birds in migration, it provides an immeasurable benefit. Additionally, an entire group of people once depended on it. Taken at face value, perhaps it may seem “little graced with the picturesque,” as Twain said. However, as scientists help us understand what lies below — and above — the surface, we realize that its sea of mysteries is very much alive and quite beautiful.

Bibliography:

Brewer, William H. “Up and Down California in 1860-1864; the Journal of William H. Brewer.” Edited by Francis P. Farquhar. Library of Congress, n.d.

Hildreth, Wes. “Volcanological Perspectives on Long Valley, Mammoth Mountain, and Mono Craters: Several Contiguous but Discrete Systems.” NASA/ADS, September 2004.

Hill, Mary R., and Mary R. Hill. “Ch. 11: Mono Lake: The ‘Dead Sea’ of the West.” Essay. In Geology of the Sierra Nevada. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006.

Hughes, Alex. “Volcanoes of the Eastern Sierra Nevada: Geology and Natural Heritage of the Long Valley Caldera.” https://www.monolake.org/.

NASA. “Unearthing Clues to Martian Fossils.” NASA. NASA.

Nystrom, Siera. Sea Monkeys!! (Brine Shrimp of Mono Lake), November 28, 2017.

Twain, Mark. 1872. Roughing It. American Publishing Company.

Russell, Israel C. “Quaternary History of Mono Valley, California, by Israel C. Russell …” HathiTrust Digital Library, 1889.

Simeone, Mono. “The Biogeography of Mono Lake Alkali Fly (Ephydra hians).” San Francisco State University, 2000.

USGS. “Mono Lake Volcanic Field.” Paoha and Negit Islands, Mono Lake, California. USGS.