Despite centuries of study and decades of exploration, there remains much we do not know about our solar system. And as the planets and moons swirl in an endless dance about each other, a mysterious hidden partner has long been rumored.

Nemesis, the hypothetical dark companion to our Sun, may lie out there. Proposed to explain Earth’s periodic mass extinctions, this elusive star remains a tantalizing enigma.

Despite decades of speculation and numerous searches, scientific evidence for Nemesis remains elusive. Are we truly orbiting the Sun with an unseen companion, or is Nemesis a cosmic phantom?

In this exploration, we delve into the shadows of our celestial neighborhood, examining the quest for Nemesis and the implications its discovery (or lack thereof) holds for both the history, and future of life on Earth.

So what is it?

Some astronomers have hypothesized that our solar system doesn’t just have one star. Instead, they believe the Sun could have a companion dwarf star, which they’ve dubbed Nemesis.

Why the ominous name? Well, scientists speculate that this dark destroyer could affect the orbits of objects originating from the far reaches of the solar system, sending them careening towards Earth and periodically causing mass extinction events.

Nemesis’s existence was first postulated in 1984 by Richard Muller of the University of California, Berkeley. He suggested that a red dwarf star could be orbiting around the sun at a distance of 1.5 million light years.

- “And Yet It Moves” – Galileo, the Planets, and the Church

- Aether: Searching for the Fifth Element of the Ancients

He began working on the theory after he and other scientists noticed that mass extinction events on Earth appeared to have a cyclical pattern, happening every 27 million years or so. It was decided that with such long time spans involved the only explanation could be astronomical (space is very, very big and it takes a long time for anything to get anywhere).

The theory evolved with later researchers suggesting Nemesis could be a brown or white dwarf or even a star so small it’s barely bigger than Jupiter (which is still larger than all other planets in the solar system put together). All these kinds of stars are very dim, which would explain why Nemesis hadn’t been spotted previously.

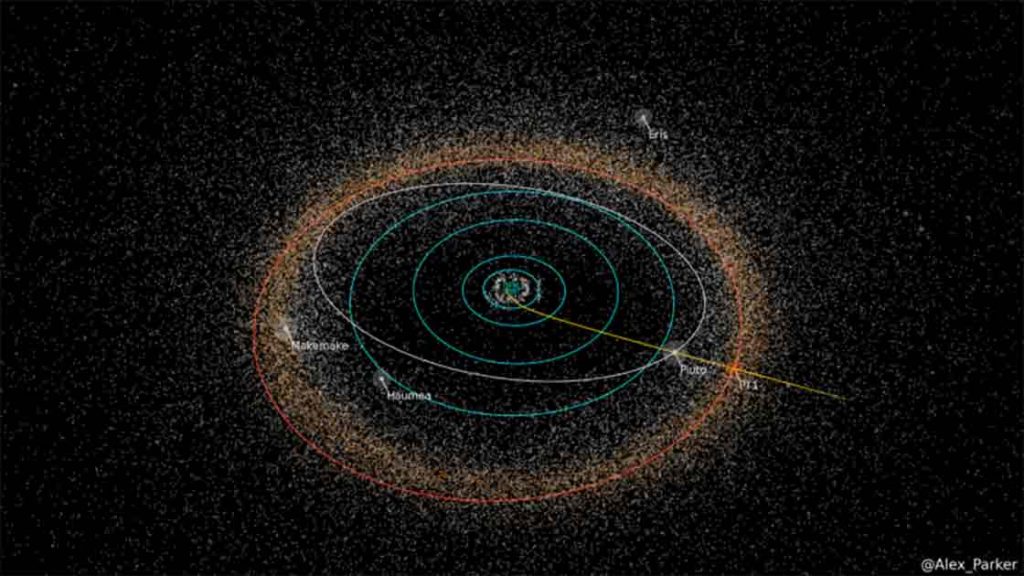

What type of star Nemesis may be may have changed from theory to theory but the main idea behind it hasn’t. Muller and his colleagues believed that if Nemesis was located beyond the Oort cloud (a ring of icy rocks orbiting around the sun past Pluto) its sheer size means that its gravitational pull could affect this band of asteroids.

The massive chunks of ice that make up the Oort cloud streak through the solar system in an elliptical orbit and as they get closer to the sun they melt, leaving a tail behind them. These are comets.

It’s been speculated that if Nemesis’s orbit takes it through the Oort cloud every 27 million years, its gravity could kick out extra comets, sending them hurtling toward the inner solar system. The law of averages means this would lead to more impacts on Earth. More impacts would mean more extinctions.

Problems with the Nemesis Theory

It’s a nice theory but not everyone is convinced. There are a few problems with the Nemesis theory.

One of these revolves around the idea that Nemesis could be causing mass extinction events. Fossil records do seem to show that extinction events seem to peak, or become more common, around every 27 million years.

The problem is that besides a handful, there’s no evidence these extinctions were caused by meteor impacts. The kind of impact needed to cause a large-scale extinction event would need to be exceptionally large. Unfortunately (or fortunately when one thinks about it), there aren’t enough craters of this size and the ones that do exist don’t all line up with the 27-million-year pattern.

On top of this, not all astronomers are convinced the math adds up when it comes to Nemesis’s orbit. The fact Nemesis doesn’t appear to affect the orbits of planets within the solar system, including the tiny Pluto, plus the fact it can’t be seen, means it must be very far away and very small.

However, many astronomers believe such a distant orbit would be incredibly unstable because at that range Nemesis would come under the influence of other stray stars traveling through the galaxy. This means its orbit wouldn’t kick through the Oort cloud every 27 million years, meaning it wouldn’t have anything to do with the extinction pattern.

A 2017 study put another nail in Nemesis’s coffin. It found that the majority of stars like the sun were indeed born with companions.

However, they also found that over time these companions drift away and break free from their bigger siblings. Simply put, if Nemesis did exist, it would have left our solar system and joined the rest of the galaxy an exceedingly long time ago.

There’s also the problem that no one has spotted it yet. A star as far out and small as Nemesis supposedly would be impossible to spot with the naked eye but telescope technology has come a long way over the last few decades. The ultra-sensitive telescopes used by today’s astronomers should absolutely be able to spot Nemesis.

Over four years two teams of astronomers located in Arizona and Chile carried out the advanced Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS) using the world’s most advanced telescopes. They scoured the sky in three infrared wavelengths looking for stars. They found 173 brown dwarfs outside of our solar system. None of them fit the bill for being Nemesis.

Likewise, from 2010-2011, Nasa’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer found some brown dwarfs closer than 20 light years away. None of these were located close enough to be Nemesis.

The failure of these, and other surveys, to find a likely candidate has led many astronomers, including those working at NASA itself, to declare that Nemesis does not exist. The Sun is a lone star and that’s the end of the story as far as they’re concerned.

So, if Nemesis doesn’t exist, what about the 26-million-year extinction cycle? Could it just be a massive coincidence? Maybe not

Other celestial goings-on could be responsible. These are too complex to detail here but basically, it’s believed other events happening either within or outside our solar system could be affecting the Oort cloud, causing it to shoot out extra comets once in a while. Or they could be sending cosmic rays into our atmosphere, triggering climate changes and extinction events.

But like Nemesis, none of these theories have been conclusively proven. As such the periodicity of extinction events remains a topic of ongoing research and debate within the scientific community.

It may not be a terrible thing this evidence hasn’t been found though. According to most of these theories we’re long overdue a mass extinction event. Something you would think most of us would rather avoid.

Top Image: Is there a hidden brown dwarf twin to the Sun in our solar system, and has this “Nemesis” star been responsible for our periodic mass extinction events on Earth? Source: Инна Архипова / Adobe Stock.