As any James Bond aficionado will tell you, every secret agent needs a foil, and the best foil must be an unkillable mirror for the hero. It can’t be an individual (a lesson today’s serialized superhero movies seem to have forgotten) for an individual can be killed, which devalues prequels and turns the hero into a glorified pest control by the fifth or sixth iteration.

Conan Doyle faced this problem with Sherlock Holmes, his prototypical secret agent, and his solution was to have both Holmes and his (just-introduced) nemesis Moriarty die. Holmes himself would later be revived, an early example of retconning based on public outcry but a tragedy for the narrative. Ian Fleming, it would seem, learned from Conan Doyle’s mistake, and gave James Bond SMERSH.

SMERSH, or SPECTRE as they became in the later novels and in the Bond films, is every inch the unkillable hydra (or most recently octopus, in a faintly disappointing downgrade of the metaphor) they are portrayed to be. Bond cannot kill SMERSH, only agents sent by them. They are the perfect antagonist for an agent (and a writer) looking for a long career.

SMERSH, however, was very real. The odd-sounding name was coined by Stalin himself, and comes from the Russian Смерть Шпионам or “SMERt’ SHpionam”, which means “Death to Spies”. This sprawling organization controlled all critical counterintelligence operations through the Cold War.

SMERSH was principally concerned with Soviet domestic security, but they would occasionally deal in more direct methods. Perhaps the most infamous of such organizations, officially never a part of SMERSH, was Service 7, the Bulgarian assassins.

Service 7

The Bulgarian Committee for State Security, better known as Service 7, was the name of the Cold War covert structure inspired by SMERSH. It began operations in mid-1963, and by 1972, it had been involved in at least ten cases involving Bulgarians who had fled beyond the Iron Curtain.

By 1989, it had carried out operations in Italy, the United Kingdom, Denmark, West Germany, Turkey, France, Ethiopia, Sweden, and Switzerland. Using clandestine methods and ignoring international law, it worked to kill dissenters and to “prevent defections after the fact”.

Service 7 had only four officers when it was established. Its Chief Colonel Petko Kovachev referred to it as “our small subdivision” in a report dated 7 October 1964. He demanded further work in the same text.

- Traitors To The Crown: Who Were The Cambridge 5?

- Assassination of Olof Palme: Who Killed the Swedish Prime Minister?

He stated that by doing so, the service would gain experience and expand its agents’ understanding. The officer claimed that there are plenty of work opportunities. By 1967, his ambition had come true: the hidden structure had 39 agents. In a memo to the chief of state security dated September 30, 1967, he requested that the work of Service 7 be discussed at the highest level possible and that the bureau’s weakest spots be identified and fixed with the assistance of Soviet comrades.

Targeted for Elimination

Each operation would have a codename: The Black, Lackey, Traitor, X, Hamlet, Betrayer, Blind Man, Ox, Widower. The assassinations and the targets were never referred to by name, and even the killing itself was to be hidden behind phrasing such as “liquidation” or “suppression”: nobody was to talk about what was really going on.

This silence remained for years after the end of the Cold war. As late as 1999, General Vlado Todorov (head of Bulgarian intelligence during the 1980s) denied that such a department existed, and insisted that Bulgaria did not take part in assassinations.

It would only be in 2010 that the documents documenting the organization’s actions were declassified. They revealed that in the 1980s the state had been actively working to “Bulgarianize” Bulgarian Turks, and that they had been responsible for the deaths of multiple dissidents and outspoken objectors, preferring to silence them.

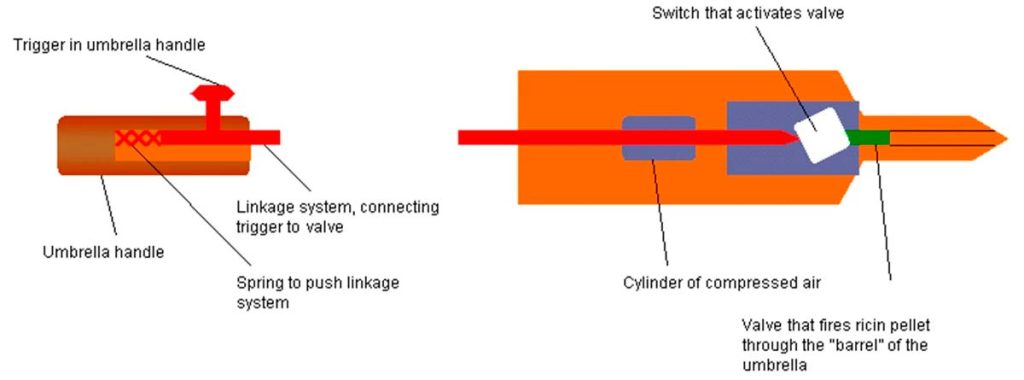

Perhaps the most famous murder carried out by Service 7 was Georgi Markov, killed on Waterloo Bridge in London. Markov, a writer and outspoken critic of Bulgaria and the Soviets, was killed by a poison pellet hidden in the tip of an umbrella, which was then stabbed into him seemingly by accident as he passed.

But in Service 7 Bulgaria and the Soviets had created a monster. The unaccountable (because secret) organization started to dabble in other activities, smuggling guns, narcotics, alcohol, cigarettes, gold, silver, and antiques as they enriched themselves. Bulgarian organized crime in the 1990s was also the surviving legacy of Service 7.

The Murders

Service 7’s first operation, codename “Libretto”, was against Bulgarian Blago Slavenov, who had fled to Italy in the late 1940s. The plan was to kidnap Slavenov and put him on a ship in Trieste, and return him to Bulgaria, where he would disappear.

The necessary equipment for the procedure was prepared with the help of the Bulgarian Ministry of the Interior’s Hospital in Sofia. According to the records, the operation included three accomplices and two Bulgarian intelligence officers.

As a leading member of the Bulgarian National Committee, Slavenov was a highly visible target and therefore the extreme secrecy that surrounded Service 7 was needed to avoid recriminations. But this first operation was a failure.

- UK Prime Minister Turned Traitor: Was Harold Wilson a Communist Spy?

- Argentina Death Flights: State-Sponsored Murder

Although Slavenov had escaped, Service 7 had learned much about the practicalities of their work and chalked it up to experience. After several years of preparation, they tried again using a female agent to persuade Slavenov to visit Vienna. This attempt was also unsuccessful.

Slavenov, it would seem, was very aware of Service 7’s activities against him and found it frustrating as he was prevented from returning to Bulgaria. Slavenov would eventually outlast the Cold War and die in 1996.

Service 7 was also involved in an attempt to assassinate Pope John Paul II in 1981, although Bulgaria has consistently refuted this accusation. During a visit to Bulgaria in 2002, the Pope kindly exonerated Bulgaria of any involvement, putting everything in the past.

In 2018, unearthed Communist Party records showed a 1971 plot to provoke a crisis between Turkey and Greece. The plan was for Bulgarian secret operatives to set fire to the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and make it appear as if it had been set on fire by Turks.

This was much more dangerous than it would at first appear. Such a false-flag act would have had catastrophic effects on the already complex Turkish-Greek relations, and would have most likely forced the US to pick a side in the impending confrontation.

Traycho Belopopski, a Bulgarian Intelligence officer who defected in 1960, was one of the first targets. Marked for liquidation in 1964 under the codenames The Black and Mavrov, he managed to survive by fleeing the UK for the United States, leaving his wife and daughter behind. They never saw him again.

Exposed

After the fall of the Soviet Union Bulgaria’s communist dictatorship fell apart, and the newly formed democratic leaders were quick to accuse the country’s old communist leadership of a cover up. It would take decades of investigation before the truth would come out.

Gen. Atanas Semerdzhiev, the former Interior Minister, was found guilty in 2002 of destroying almost 150,000 documents from the intelligence archives. Five years later, on April 5, 2007, the Bulgarian parliament established a special committee for revealing documents and notifying Bulgarian citizens of any unlawful activity against them from the Bulgarian National Army’s State Security and Intelligence Services.

It also began investigating those who had previously held or currently hold public positions to see if they had any ties to the organization. However we may never know the true extent of Service 7’s criminal activities.

Top Image: The activities of Service 7 were kept secret until 2010. Source: New Africa / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri