In Greek mythology, the Sibyl was originally a solitary prophetess who was famed for the precision of her prophecies. Many thought she was divinely inspired, driven to contorted madness by the visions the gods sent her.

As time passed, other Sibyls appeared in various parts of the Mediterranean region, including the legendary Cumaean Sibyl, whom Aeneas is said to have consulted.

Sibylline prophesies were finally compiled in writing in Rome. Roman rulers employed them to understand strange phenomena or natural catastrophes or to provide guidance on important issues related to foreign entanglements and conflicts.

Legend tells that the Last King of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, acquired the collected Sibylline books for the glory of his growing kingdom. Purchased from a soothsayer gifted with foresight, these books had magical properties and would be consulted to guide Rome to greatness.

What was contained in these magical books, and where are they today?

Sibylline Prophecy

The twelve volumes of prophetic knowledge that make up the extant Sibylline Books, known as the Sibylline poems, were old even for the Romans. Written in Homeric Greek hexameters, they were crafted over several centuries by multiple unknown authors.

They are a jumbled collection of doomsday predictions, historical allusions, end-of-the-world prophecies, and criticisms of many peoples, particularly (as the Romans thought) the Romans themselves, for their neglect of piety and indulgence in vice.

By using the voice of Sibyl, anonymous Jewish and Christian authors would later speak out against perceived injustice, corruption or excess, using “prophecy” to denounce those in power for their involvement in idolatry, licentiousness, and other vices. Several books provide vivid descriptions of the end times and the apocalyptic inferno.

Nor was the text a fixed document. Later Christian authors added their own revelatory passages, which co-opted the Sibyl’s reputation for foresight but which emphasized Christ much more, as you would expect.

The first time Sibyl is shown is as a Greek prophetess who received heavenly inspiration for her prophecies. The scholar Heraclitus, who wrote his writings in the late 6th through early 5th century BC, is the source of our oldest mention of her.

- What Is the Oracle of Delphi and How Did She Prophecize?

- The Marian Reforms: A Thoroughly Modern Roman Army

Heraclitus describes her as a lone figure, a raging seer in the wilderness who spoke in a god-like manner, without humor or embellishment, and with a voice that echoed throughout the universe. After then, the tradition fragments, and the Sibyls become more numerous.

The prophetess of Heraclitus may have been a lone voice that spoke without regard to location or time for a thousand years. Yet, later references mention several Sibyls, who were assigned to certain places and who stood in for different, maybe rival, shrines.

Heraclides Ponticus, a philosopher of Plato’s Academy and a polymath, authored a book on oracle shrines by the middle of the 4th century BC which noted many Sibyls throughout the Mediterranean region. He dryly recorded copycat Sibyls in Marpessus, Troad, Erythrae, and Delphi.

Nascent attempts at brand recognition are also apparent. The Erythraean Sibyl was known as Herophile, and the Delphic Sibyl is said to have come out of the distant past as a contemporary of Orpheus.

The Marpessian, on the other hand, was a newer prophetess; according to Heraclides, she lived during the reigns of Solon and Cyrus, i.e., the 6th century BC. But the inference was clear: if you wanted to run a temple of import, you needed a Sibyl to attract paying pilgrims.

The most famous Sibyl is of course the Oracle at Delphi, wo appears in Homer and predicts the Trojan war. The Sibyl endured for hundreds of years, had been claimed by the Delphians as a child of Zeus by the time Pausanias lived in the 2nd century AD.

Alternatively, she had been claimed to be the daughter of a nymph and to have been located at Marpessus, whose ruins Pausanias had personally visited. Significantly, Herophile was claimed by both Marpessus and Erythrae; it seems that rival Sibyls would also squabble from time to time.

The Sibylline Books of Rome

We know of the Sibylline books primarily through the account of the historian Lactantius, an easrly Christian author and advisor to Emperor Constantine I. Lactantius is himself quoting an account by Varro, possibly ancient Rome’s greatest scholar, who outlines the story.

Varro’s account talks or the last king of Rome, who ruled before Rome reinvented herself as a Republic in 509 BC. An old women, believed to be a soothsayer and known as the Cumean Sibyl herself, approached Tarquinius Suberbus and sold him nine books of prophecy.

Whether or not the story is true and these oracles were obtained in Tarquinius’s time, they were said to be kept at the Sanctuary of Jupiter Capitolinus and were utilized on several occasions during the life of the Roman Republic, and the later Roman Empire, when Rome faced crisis.

- Odysseus’s Oracle of the Dead: A Gateway to Hidden Knowledge?

- What Was Silphium? Lost Wonder Drug of the Romans

The more skeptical reader will already be seriously doubting almost everything about this origin story. Mystical books offering divine guidance which the public are not allowed to read sounds a lot like made-up oracular support for whatever rulers wanted to do: don’t argue with my politics, the Sibyls said it was for the best etc.

The fact that the original texts were heavily modified and many additions were made over the centuries also supports this concern. However the Sibylline books were something else as well: an important part of the Roman identity and Roman exceptionalism, much like US politicians cite the Constitution and the intentions of the Founding Fathers in their politicking today.

In truth, and just like the US Constitution, the texts of the Sibylline oracles that have survived have nothing in common with what was created by Roman authorities for public consumption. What we know of the books from the surviving collection reveal them to actually be literary works written primarily in Greek hexameter.

Numerous Jewish and Christians created it, and possibly a few pagan authors between the second century BC and the seventh century AD, all of whom had different goals and agendas. The Sibylline Books are divided into two main groups containing twelve volumes and other fragments.

Central to the Roman Identity

Fifteen high ranking people were responsible for looking after the Sibylline Books, which were held on the Palatine Hill in Rome. Under the direction of the Senate, officials consulted the Sibylline Books in times of crisis, to seek guidance on preventing disasters rather than detailed prophecies of specific future occurrences.

There were many opportunities for misuse as only the rituals of expiation recommended by the Sibylline Books were shared with the whole public. The people of Rome only got the advice after it had been interpreted by their leaders.

Certain sea-changes in Roman behavior came from the advice of the books. The worship of Apollo, the Magna Mater (“Big Mother”) Cybele, and Ceres all grew in popularity based on advice translated from the Sibylline Books, for example.

As a result, the Sibylline Books significantly shifted Roman religion away from the Etruscan beliefs which came from Italy towards Greek gods. The Sibylline Books were the driving force behind the construction of eight shrines in ancient Rome, and the famous Roman pantheon of gods we know today are just a rebranding of older, Greek gods.

Researchers believe that after centuries of adjustments and amendments, the books met their end in the 5th century. The Roman general Stilicho, with barbarians almost literally at the gate and the fate of Rome in the balance, despaired of the public faith in them and had them burned in 405 AD.

Stilicho himself was unable to save Rome, being himself executed three years later, with Rome falling to the Goths shortly after. Perhaps the words of the ancient Sibyls had protected Rome, after all.

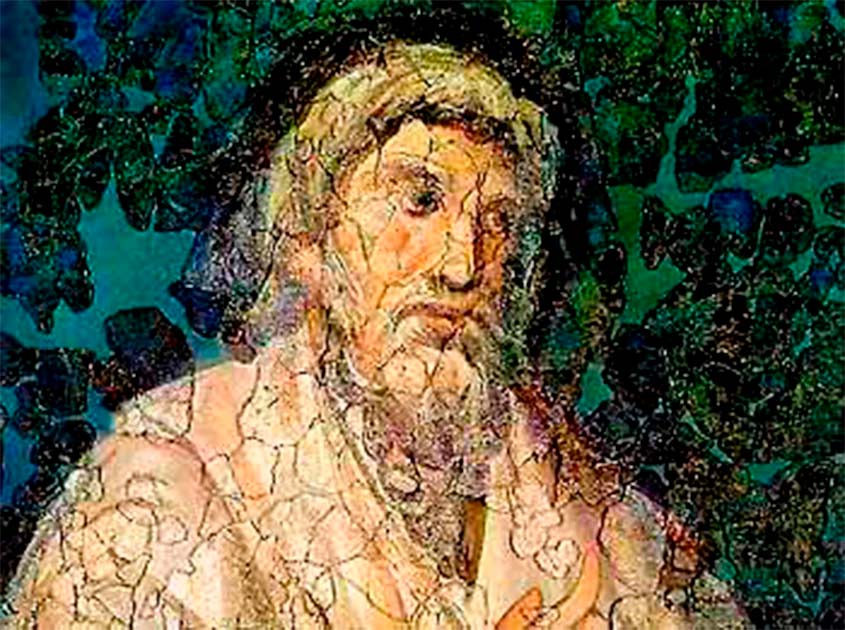

Top Image: The Cumean Sibyl by Michelangelo, one of multiple Sibyls depicted in the Sistine Chapel. Source: Michelangelo / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri