Imagine that you are a parent and are having a typical Saturday with your children. Now imagine your day being interrupted by police and social workers bursting into your home and dragging your crying and screaming children away with no explanation as to why your children were taken away and where they are going.

Now imagine that your children are being placed in foster homes suffering physical and sexual abuse or adopted by non-indigenous families and receiving little to no information about the adoption. It is every parent’s worst nightmare and is horrible to imagine. Yet this was what life was like for families and children in indigenous communities across Canada for decades during what is known as the “Sixties Scoop”.

The Sixties Scoop

The Sixties Scoop refers to a time in Canadian history from the mid-1950s through the 1980s when the Canadian government created policies allowing child welfare authorities to remove indigenous children from their homes. Children were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to foster homes, adopted by white families, separated from siblings, or placed into residential schools.

The Sixties Scoop was seen as a response to residential schools. Before discussing the Sixties Scoop further, it is important to know what residential schools were like.

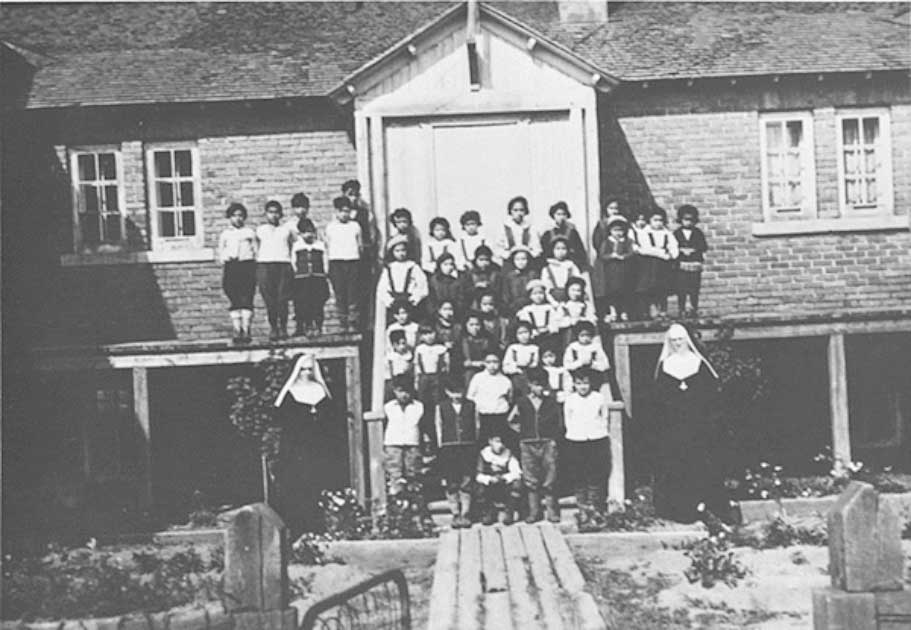

Residential schools were “schools” that indigenous children were sent to in order to “become civilized and learn Euro-Canadian and Christian values”. The Catholic church ran these schools, and the children in these schools were subject to horrendous conditions.

Children were known only by numbers and would be beaten if nuns or priests caught them speaking to another child in their native languages (many students did not know a word of English or French before coming to the schools). The children were often fed very little or were forced to eat things like apple peel off the ground, while the priests, nuns, and school administrators would eat steaks and substantial meals in front of the starving children.

The students at these residential schools faced traumatic physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, and brutal sexual abuse from the adults in the schools and even from older children. When students left these schools, they were traumatized and tried to escape their childhood memories, often through drug use and excessive drinking.

These individuals, who grew up in an incredibly abusive environment, began to start families where they would treat their children and spouses violently and severely because it was all they knew. The lasting effects of residential schools in indigenous Canadian communities are still felt and seen today.

A few lawsuits have been levelled, but many survivors do not want financial compensation for their years of abuse; they want justice. These suits often require victims to face brutal questioning and re-traumatize themselves and often are told they are lying or the abuse never happened. The last residential school in Canada closed in 1996, thankfully.

The “Goals” of The Scoop

The goals of the Sixties Scoop were to assimilate indigenous children and provide better care for them. The government and social workers were under the impression that indigenous families could not properly care for their children, especially single mothers.

It was believed the children would be better off if they were placed in foster homes and adopted by white families across Canada, the United States, and Europe. Removing children from families who can not care for them is seen worldwide, but it was different during the Sixties Scoop.

The children were taken from their homes without warning, consent, or knowledge if a parent or an adult wasn’t home at that moment. There was no need to provide proof of abuse or harmful living conditions.

Social workers could come to a reservation and remove children and never tell their parents or members of the tribe where the children were going, why they were taken, or who they were adopted by if that occurred. Residential schools and the Sixties Scoop were seen, horrifyingly, as a way to “get rid of the Indian problem” in Canada.

The goals set during the Sixties Scoop were met, in a way. Indigenous children were sent to foster homes and adopted by white families. They left behind their family, culture, languages, and communities and were forced to assimilate into a white world where they knew they didn’t belong. Overall, the only thing that was actually achieved during the Sixties Scoop was a massive failure to protect or care for indigenous children.

The Children

Children in foster homes were abused; some were forced to sleep outside in tents while the white children (even white foster children) were allowed in the house. Children may have seemed happy to be adopted, but this was because they were able to escape their foster homes.

Adoptive life was often just as bad as their time in foster homes. Children would constantly run away and try to return to their homes, or some would choose a life on the streets or commit suicide over having to stay in group homes and with adoptive parents.

The children knew they were different from their white peers, were subject to racism, and those who were very young when they were adopted and couldn’t remember their life before didn’t even know they were indigenous people or their own heritage and native languages. Statistics provided by the Canadian government estimate that 11,132 indigenous children were adopted during the Scoop. Many believe that number is incorrect, and it is estimated that white families adopted potentially 20,000 children.

The events of the Sixties Scoop are now considered to be cultural genocide.

The Aftermath

Culture itself is the teachings of ancestors and is the basis for all customs, values, ways of knowing/being, traditions, languages, ceremonies, and spirituality. Our culture shapes who we are, even if we are unaware of it.

- Your Child Is Not Your Own? The Horrific Tales Of Medieval Changelings

- What Caused the Pink Poop Pandemic?

Cultural identity is “the identification with, or sense of belonging to, a particular group based on various cultural categories, including nationality, ethnicity, race, gender, and religion.” Losing your culture and cultural identity has been shown to cause deterioration of someone’s health and mental well-being.

Many children impacted by the Sixties Scoop felt like even when they finally learned they were adopted and from where and felt they couldn’t return home because they didn’t belong in those communities. Where do you go, and what do you do when you think you don’t belong in the white community or the indigenous one you came from? This is just one of the questions many indigenous children and adults who were part of the Sixties Scoop still ask themselves to this day.

Child welfare services in Canada began to change in the 1980s when indigenous and non-indigenous communities started to criticize the country’s welfare system and bring an issue to the fact that most children in provincial care were indigenous. While this did lead to the establishment of indigenous-controlled child welfare agencies, nothing was truly ever solved.

Indigenous welfare agencies are vastly underfunded, which impacts the well-being of children in the welfare system today. Several provinces have issued formal apologies to their indigenous peoples, and Sixties Scoop survivors are entitled to financial compensation of around $25,000. Still, the process is slow-moving and requires a survivor to be “Status Indians” or officially recognized members of a federally recognized tribe in order to receive financial restitution.

Thousands of Sixties Scoop survivors are searching for their siblings who were relocated to an unknown part of Canada and the United States. Some siblings do not know where their siblings went, their adopted names, if they are still alive, or if they are deceased, where their graves may be.

The Sixties Scoop and residential schools resulted in generational trauma, which negatively impacts a person’s parenting skills, values, financial situation, and future success of both survivors and their children. Trauma from the Sixties Scoop has resulted in alarmingly high rates of substance abuse, domestic violence, child abuse, mental illnesses/depression, alcoholism, homicide, and suicide within the Indigenous First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities across Canada.

To this day, many non-indigenous Canadians do not know that the Sixties Scoop occurred, nor are they able to comprehend its impact on indigenous peoples and their communities fully. The healing process for survivors of the Sixties Scoop and residential school system is complicated, with many unwilling to talk about their traumatic experiences.

The government-formed support programs are underfunded and unable to help survivors or their families adequately. However, through podcasts*, protests, articles, and education initiatives, more and more people across the globe are now learning about and hearing stories of survivors of the Sixties Scoop and residential schools.

Top Image: The Sixties Scoop saw indigenous children taken from their mothers and given to white families so they could grow up with western values. Source: Globalmoments / Adobe Stock.

By Lauren Dillon

* The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s lead reporter for their Indigenous reporting unit, and indigenous woman Connie Walker, has produced several podcasts about the Highway of Tears, The Sixties Scoop, and residential schools available for people to learn more about the treatment of indigenous Canadians. The second season of her show Missing & Murdered is focused on the search for information about a family’s sister who was taken during the Sixties Scoop. To listen to this podcast, and learn about the Sixties Scoop, search for “Missing & Murdered: Finding Cleo” on any podcasting network or app.