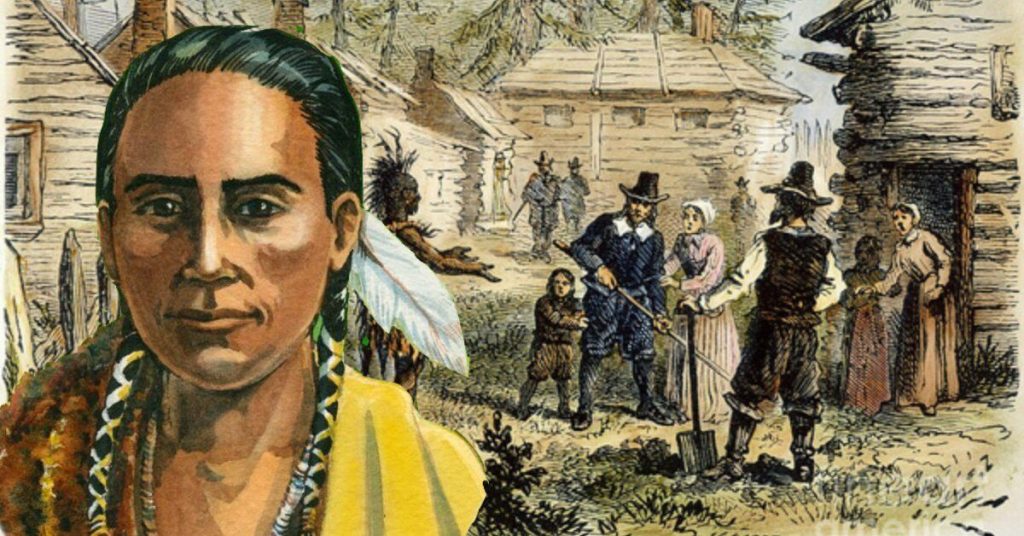

Squanto, or Tisquantum, was a Native American guide who assisted the settlers of the Plymouth Colony during their harsh early years. But Squanto’s life was much more eventful and indeed tragic. Before ever meeting the Pilgrims, he was sold into slavery, traveled throughout Europe, and became the last living member of his tribe. Squanto would later become a key political ally to the settlers of Plymouth Colony. Without his guidance, it’s doubtful the colony would have survived.

Early Life

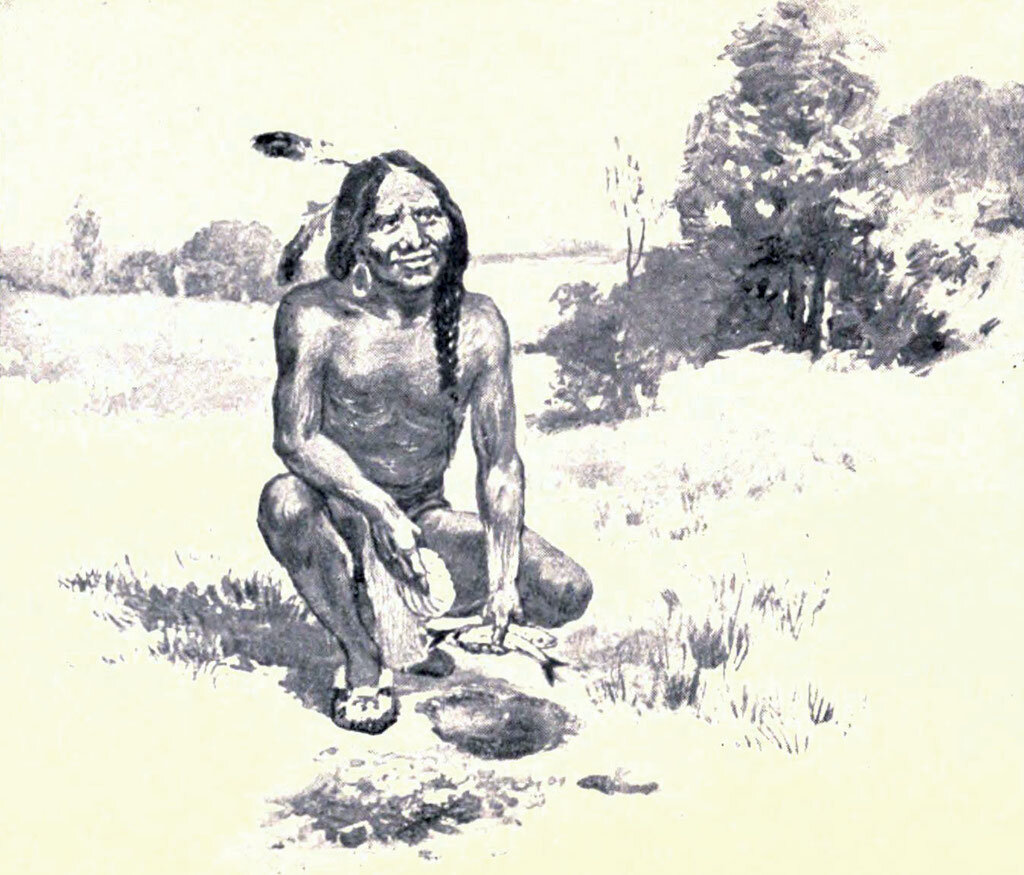

Tisquantum, or Squanto, was probably born around 1580 near Plymouth, Massachusetts, or “Dawnland” as the Wampanoag tribe called it. He was a member of the Patuxet tribe, one of about a dozen tribes that comprised the Wampanoag Confederacy. They spoke an Algonquian dialect, Wampanoag. They practiced agriculture as well as hunting and foraging. Squanto’s birth name probably wasn’t Tisquantum, which means “rage” in Wampanoag. His actual birth name is unknown.

Sold Into Slavery

In this time, sea captains on the Transatlantic Trade Route commonly made extra revenue by capturing indigenous peoples and selling them into slavery. Squanto is known to have been captured and enslaved at least once. Some scholars believe this was in 1605 when an English captain named George Weymouth might have captured him in Maine among a group of Penobscots. Others argue that he was kidnapped in Massachusetts in 1614 by Captain Thomas Hunt. The captain lured them onto his ship by promising to trade with them. He then locked them below deck and sailed for Europe.

Some believe that Squanto was sold into slavery in Málaga, Spain and that he escaped with Spanish friars help. But there’s more evidence to suggest that he spent most of his years in captivity in England. Clerics likely tried to convert Squanto to Christianity without success. It’s also possible that Squanto met Pocahontas during his time in England.

During these years, Squanto learned English. This skill would make him indispensable as an interpreter between Europeans and indigenous peoples. In 1619, an English explorer named Thomas Dermer brought him back to New England on a trading exposition. But when Squanto finally arrived in his homeland, he made a terrible discovery.

The Last Patuxet

The arrival of Europeans in North America meant the arrival of new diseases to the continent. With no previous exposure to these diseases, indigenous people had no immunity. Some estimates indicate that 90% of all indigenous peoples in the Massachusetts Bay Colony area died from disease brought by European explorers. This massive population collapse allowed European settlers to move in and colonize the land.

In 1617, a plague had wiped out nearly all of the Patuxet people. Today, historians believe this epidemic was an outbreak of smallpox. Although some evidence suggests it may also have been leptospirosis, a bacterial blood infection found in rat urine. Perhaps a combination of both. By 1620, the Patuxet was considered extinct. The Plymouth colonists would choose the site of the Patuxets’ village to build the Plymouth colony.

Aiding Massasoit

With none of his people left, Squanto remained with Dermer. Squanto and Dermer next visited the Pokanoket tribe, another member of the Wampanoag Confederation. The Pokanokets, led by their ruler or “sachem” Massasoit, were hostile to Europeans. Earlier, a European captain had lured a group of Pokanokets onto his ship and murdered them. But Squanto convinced the Pokanokets to spare Dermer. Massasoit realized Squanto’s unique value and hired him as his interpreter.

The arrival of the Plymouth colonists in 1620 presented Massasoit with a dilemma. The plague had also decimated the Pokanokets. Now weakened, they were vulnerable to their enemies, the neighboring Narragansett tribe. Massasoit could attempt to form a coalition of indigenous people and drive out the colonists. But Squanto, who had lived among the British and had seen their technical advantages, convinced Massasoit that an alliance with the Europeans would strengthen the Wampanoags. This way, the Narragansetts and the rest of Massasoit’s enemies would be “Constrained to bowe to him.”

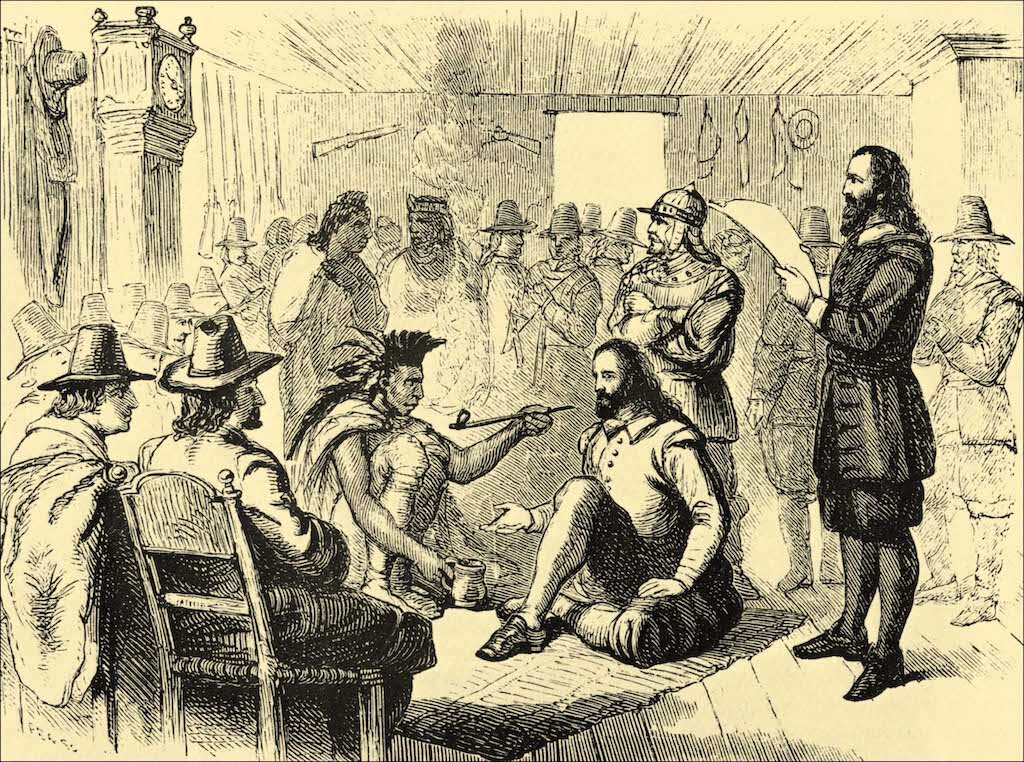

A Key Emissary

The Pokanokets made multiple visits to the Plymouth Colony to establish diplomatic ties. As the interpreter, Squanto negotiated a peace and mutual defense treaty between the Pokanokets and the Pilgrims. After Massasoit departed, Squanto stayed behind and lived at the Plymouth Colony. He developed a close relationship with the colony’s governor, William Bradford, and became his main emissary.

Squanto played a crucial role in navigating the relationships between the Pilgrims and the surrounding tribes. He helped locate a Pilgrim boy named John Billington who had wandered off into the wilderness. He established trading relationships between the Pilgrims and both the Nauset and the Cummaquid tribes. A rival Wampanoag sachem named Corbitant captured him, and Governor Bradford organized an armed party to rescue him.

Eventually, relations between the Plymouth Colony and the Narragansett deteriorated. Suspicion arose that Squanto negotiated in bad faith, using his position to deceive both sides and enrich himself. It’s unknown whether these accusations were valid, but both Massasoit and Governor Bradford grew to mistrust Squanto. At one point, Massasoit demanded his execution. But his role as an interpreter made him too valuable to kill.

Thanksgiving

The Mayflower Pilgrims did not intend to live in New England. Initially bound for Virginia, storms diverted them north. They made landfall 65 days after their intended arrival, on November 11th. The winter of 1620 was particularly harsh. Inhospitable weather combined with a lack of food killed over half of them.

As a local, Squanto also had considerable knowledge of the area and its soil. In addition to facilitating the Pilgrims’ diplomatic relations, Squanto also advised them how to plant corn. One famous story is that he taught them to fertilize the soil using fish, but this may be fictional.

Related: First Thanksgiving: What Was it Really Like for the Pilgrims?

Whatever the method, Squanto’s advice helped the Pilgrims make a successful harvest in the fall of 1621. To mark the occasion, the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag held a three-day feast that would later become known as the first Thanksgiving. Most likely, turkey was not on the table, although they probably ate wildfowl. Deer, cornmeal, pumpkin, succotash, and cranberries were also on the menu. But not sweet potatoes, which hadn’t been introduced to North America, nor pie, since the Pilgrims had no oven.

Death of Squanto

In November of 1622, Squanto accompanied William Bradford on another trading and diplomatic mission. Suddenly, he died at Mamamoycke (Chatham, Massachusetts, United States) on 30 November 1622. Governor Bradford attributed it to “Indian Fever,” which was likely the same plague that wiped out the Patuxet. However, modern historians have speculated that a vengeful Massasoit may have poisoned him.

Since Squanto eventually did convert to Christianity, later generations of Puritans regarded him as a model native. An example to other unconverted indigenous people. The conversion to Christianity would lead to Squanto’s depiction as a “noble savage,” a misconception that survives today.

You May Also Like: Roanoke Colony Disappearance is Still a Mystery

Squanto was very much a product of his times. He managed to survive even when taken to a completely unfamiliar world. He proved to be an adept negotiator and politician, and this may have been his downfall. But since so few contemporary indigenous sources from this period have survived to the present day, we will most likely never know who the real Squanto was.