It was the summer of 1485. The infamous War of the Roses had been brought to a close, ending three decades of civil war. Henry VII was crowned king by conquest. But with the dust barely settled on Bosworth Field, it wasn’t long before a different kind of threat would visit death and destruction upon England – a threat which had no allegiance to house or color. To physicians, it was known as Sudor Anglicus; to everyone else, it was the ‘sweating sickness’, or simply, the ‘English Sweat’.

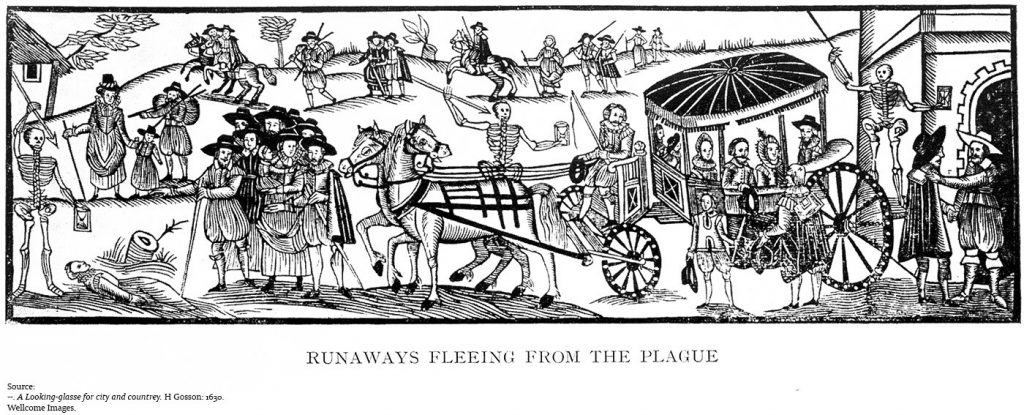

Wellcome Images” width=”1024″ height=”415″> Frank Percy Wilson “Runaways fleeing from the plague, a 1630 woodcut from ‘A Looking-glasse for City and Countrey’. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Within weeks of the first outbreak, the sweating sickness was to claim the lives of 15,000 men and women. It was, according to contemporaries, unlike anything seen before. While scientists and historians have been able to identify the pathogen that caused the Black Death, the same cannot be said of the English Sweat. The disease returned five more times throughout the first half of the Tudor period, erupting for the final time in 1555.

“Not A Sweat Onely…”

Our main sources of information for the disease are two Tudor physicians: Thomas Le Forestier, who was writing at the time of the initial outbreak, and Cambridge scholar John Caius.

In Thomas Le Forestier’s account, we see a shocking glimpse of the terror it visited on London:

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Thomas Le Forestier”]”We saw two prestys standing togeder and speaking togeder, and we saw both of them dye sodenly. Also in die—proximi we se the wyf of a taylour taken and sodenly dyed. Another yonge man walking by the street fell down sodenly.”[/blockquote]

Though he was not born until after the second epidemic, his 1552 publication, A Boke, or Counseill against the Disease Commonly Called the Sweate or the Sweating Sickness, followed shortly after the fifth and final outbreak. In it, he described the Sweat as a fever. Patients would suffer from headaches and stomach pains, as well as pain in the back, shoulders, arm, legs and other extremities.

The English Chronicler Edward Hall provides perhaps the most graphic account of the deadly sweat, which caused men to throw off their bedsheets and discard their clothes. Continued sweating aroused an insatiable thirst in those who were infected. Unfortunately, for those around them, there was no escaping the stench of fetid perspiration.

Euricius Cordus (1486-1535 drawing of the Sweating sickness, Strassbourg: 1529.

Credit: Wellcome Images. Creative Commons Attribution only license CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

According to Caius, the disease lasted for approximately twenty-four hours. Observers believed that if the patient could be kept awake for the critical first day then the chances of recovery improved significantly. The patient was actively encouraged to sweat and would be wrapped in as many clothes as possible. This was believed to be the most effective way to purge them of the sickness.

Symptoms of Sweating Sickness

The first symptom of the sweating disease would be an attack of trembling upon the person, as with a high fever. There would then be pain all over the body, followed by an overall feeling of exhaustion. Then the sweating, which gave the illness its name, would attack the patient. The person may then experience a headache, lightheadedness, and an insatiable thirst.

Over time the exhaustion would become overwhelming and the person would fall into a sleep from which they would never wake up. Unlike the Plague and other common diseases of the time, there would be no eruptions on the skin or rashes of any kind. Often the time between onset and death would be less than a day, sometimes a matter of a few hours.

Contemporaries On The Causes Of The Sweat

One theory popular throughout the late middle ages and into the early modern period was that the disease spread by ‘miasma’ or noxious air. The Roman physician Galen had previously advocated the isolation of patients to remove them from airborne risks. Both Caius and Forestier suggest that the English Sweat spread through the air.

In Tudor England, the disease was still understood primarily in terms of Galenic humoral theory. Four basic personality temperaments were likened to the four elements: earth, fire, wind, and water. Each element had a corresponding bodily fluid: black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm. An excess or imbalance of any one of these fluids or elements in the early modern period was understood to lead to undesirable personality traits like hot-headedness or melancholia; gender abnormalities, and illness.

The English Sweat.

John Caius offers some possible explanations of the sweating sickness that fit neatly within this humoral conception. This includes overindulgence or eating unhealthy or rotten foods. The Italian physician also Girolamo Fracastoro advised sufferers to avoid wine, or at the very least consume it in moderation. Overindulging was believed to add ‘heat’ to the body. Keeping the house well ventilated was of the utmost importance, as by becoming ‘heated’ you were opening up the pores of your skin and exposing yourself to the contagion.

The Sweat And The Aristocracy

Another distinction between the English Sweat and other epidemics of the period was its apparent predilection for young men of the aristocracy. This was so clear to contemporaries that the disease even earned the nickname ‘Stop-Gallant’.

Arthur, The Prince of Wales, may have died of the English Sweat in 1502. Image: Public Domain.

According to John Caius, the Sweat typically affected men of wealth and those who lived with ease. The poor were also at risk. Though the disease would typically present those who were idle and spent too much time in taverns.

An Ill Omen?

Henry VII secured a stunning victory at the Battle of Bosworth, marking the end of the tumultuous period of the Wars of the Roses. Henry’s claim to the throne was, however, tenuous at best. A ruling by ‘right of conquest’ was ruling on shaky ground.

Polydore Vergil, an Italian church official who came to England in 1502, reads the disease as a judgment passed on the new ruling family:

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Polydore Vergil”]This sweating sickness was claimed to portend the harshness of the monarch towards his people, by which almost all were heavily oppressed, and under which they ‘sweated’, that is to say were forced to undergo many discomforts both at the start and finish of his reign.[/blockquote]

Vergil may have been commenting on the reign of Henry VII here. However, the disease reappears throughout the reign of Henry VIII. Unpopular and oppressive policies like private land enclosure and the dissolution of the monasteries could have led many to view the sickness in a similar light.

The Impact Of The Sweating Sickness.

Television series such as The Tudors and the BBC adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall has revived interest in the sweating sickness. However, as a historical disease, it remains largely overshadowed by pandemics like the Black Death.

One of the reasons for this, as John Caius suggests, is that it appears to affect only the English. Indeed, the English Sweat occurred almost exclusively in England, with major outbreaks in 1485, 1508, 1517, 1528, and 1551. The only exception is in 1528-29 when it spread to the continent. It reached as far north as Norway and Sweden and as far east as Russia.

Bizarre Cases of Mass Hysteria in History

Caius and Hall present a dramatic picture of the sweeping devastation caused by the Sweat. But it’s worth remembering that, in these ‘pestilence treatises’, exaggeration is always the rule. Compare demographic figures for England in the 14th century to the 15th and 16th century and the difference is stark. As a result of the Black Death, the population decreased in the 14th century from 5.0 to 2.5 million. However, the population grew from 2.5 million to 4.4 million over the latter period, in spite of the English Sweat, and other epidemics.

The Real Cause Of The Sweating Sickness

As virologists James Carlson and Peter Hammond suggest, the ‘Sweat’ remains one of the most compelling mysteries in medical history. The range of clinical and epidemiological features that characterized The Sweat set it apart from other epidemic diseases of the Middle Ages such as the bubonic plague, typhus, and malaria.

Medical historians have suggested links to the hantavirus, as well as the Picardy Sweat which followed almost a century and a half later in France, though the symptoms differed in each.

The origins of the sweating sickness also remain unclear. One theory is that French mercenaries hired by Henry Tudor to help secure the throne brought the disease. Though there are several pieces of evidence that shed doubt on this claim. Lord Stanley already used “The Sweat” as an excuse to abandon Richard III before the Battle of Bosworth. There are also reports of a pestilence that closely resembled the sweat in the York Civic Records three months before this invasion.

There’s no doubt that the English Sweat left an indelible impression on the minds of contemporaries. Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure featured it over half a century later. Unfortunately, with no available tissue samples or evidence of any particular causal agent, all argumentation remains purely speculative. In truth, we may never know the true nature and scale of the sweating sickness.