Six sponge divers and their crew were blown off course just before the Easter holiday, 1900 in the Mediterranean between the islands of Kythera and Crete. They found calmer seas and dropped anchor in unfamiliar waters near the tiny island of Antikythera, located southeast of Kythera. Hoping to find sponges, they decided to dive but had no luck. What they did find, however, was a badly decomposed, encrusted hull of a trading ship that sank around 80 B.C. – just before the Cleopatra era and Imperial Rome.

This was the first-ever discovery of an ancient ship, so the government of Greece sent the divers back on a Navy ship to dive 140 feet back down to the wreck. They dove for a year, recovering statues, amphora, and other artifacts from the shipwreck. Keep in mind, this was done before scuba tanks and breathing apparatus were invented. It took a total of nine minutes to get from the surface of the ocean down to the dive site. By the time they were done, one diver had died and two others permanently crippled.

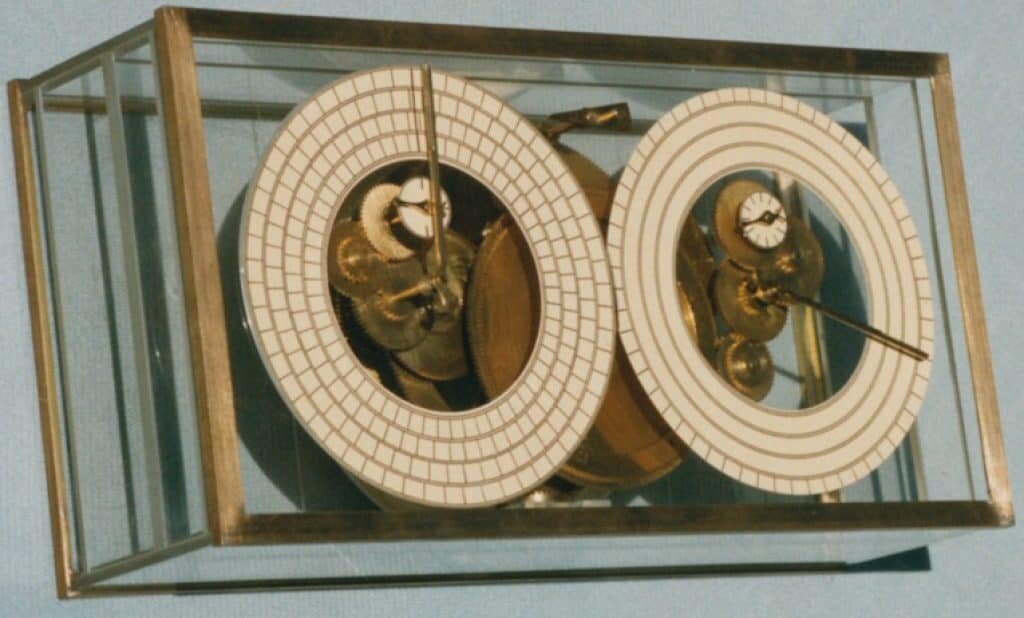

Of all the artifacts recovered, one item, in particular, drew the interest of scholars. A badly corroded set of brass gears encased in a wooden frame. The face of the mechanism had been crushed by the weight of the vessel but the rest of it was coated with a hard calcareous deposit and metallic salts, preserving much of the former shape of the bronze during the almost 2,000 years it lay submerged.

The fragments of this mechanism lay in a museum until 1971 when Yale historian Derek de Solla Price viewed the remnants of this device using gamma rays, enabling him to see through the build up of calcareous in which the gears were embedded. His findings force us to re-examine what is believed about technology in the ancient world, among other things. Needless to say, there is no trace of anything like it until 1000 A.D.

Price’s monumental study shows “the box contained 32 gears, accurately assembled in a box that reproduced the motion of the sun and moon against the background of fixed stars with a differential giving the relative position and the phases of the moon.” His report goes on to say, “the careful counting of teeth and the way the gears are meshed showed that the gear ratios could be associated with astronomical and cylindrical parameters and allowed the almost complete description of how the device must have functioned.”

Price attempted to reconstruct the mechanism and theorized that the user would rotate a shaft and get a readout on the dials that would determine the progressions of both the lunar months and synodic months (the period between consecutive new months) over four-year cycles.

In 2002, Allan George Bromley, an Australian computer scientist, along with Michael Wright, built another reconstruction model of the mechanism. Wright built a reconstruction model using better X-ray images taken by Bromley. They challenged Price’s theory stating his findings were not entirely accurate. Bromley and Wright believe both back dials have different functions and also that there was a mechanism under the front dial that was lost. This model alludes to the fact that the Antikythera Mechanism was actually an orrery, a device mentioned in ancient literature that showed the positions of the heavenly bodies using a large clockwork mechanism.

The Antikythera Mechanism is currently being studied by scientists from Cardiff University, the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, X-Tek Systems UK, and Hewlett-Packard as part of the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project.

The Antikythera Mechanism is probably the most complicated piece of ancient machinery ever discovered.

REFERENCES:

The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project

Science Daily