In 1487 during the Inquisition, two Dominican friars, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger published the witch-hunters’ book, Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches). The misogynistic manual promoted the idea that women are inherently evil and form pacts with the devil. As a justification for Kramer’s unfair trials and horrific acts of torture, the book incited church authorities and civic judges to murder 60,000 victims for witchcraft in the 16th and 17th centuries.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Heinrich Kramer”]”They [witches] take the unguent which . . . they make at the devil’s instruction from the limbs of children, particularly of those whom they have killed before baptism, and anoint with it a chair or a broomstick; whereupon they are immediately carried up into the air.”[/blockquote]

About the Malleus Maleficarum

The purpose of the Hammer of Witches was to prove the existence of witches, help hunters identify them, and suggest methods for trying and torturing the accused until they confessed. It includes passages about sorcery and spells, gives details on types of magic, and provides methods for questioning witnesses and interrogating and torturing suspects. Kramer wrote some of the material in the book based on the witch trials he conducted.

Prior to the witch hunters’ handbook, lack of support for Kramer’s cruel extremism led Kramer to appeal to Pope Innocent VIII. The Catholic leader deplored the perceived spread of witchcraft in Germany. In a 1484 papal bull decree, the Pope legitimized Kramers methods and gave him full authority to execute the search for witches. Some people suggest that Kramer paid the pope money for this bull that authorized widespread prosecution and execution of suspected witches. Three years later, the Hammer of Witches emerged.

Eventually, Hammer of Witches made its way into the hands of 30,000 witch hunters, thanks in part to Johann Gutenberg’s new publishing press. Twenty-eight editions of the book printed between 1487 and 1600. It became a handbook for the Inquisition in general, not just for witch trials.

Still, many clergies did not support the ideas presented in the manual. In one example, the authors asked the Dominicans of the Inquisition at the University of Cologne for their endorsement. However, the authorities rejected the request. Instead, they condemned the manual for unethical and illegal methods and for contradicting Catholic doctrine on demonology.

Who Wrote the Witch-Hunter’s Handbook?

Heinrich Kramer and Johann Sprenger authored the Hammer of Witches. Both of them were Dominican friars. Ironically, the Dominicans are a Catholic religious order that Saint Dominic, the patron saint of falsely accused people, founded. He represented kindness and compassion.

Kramer was a Theology professor at the University of Salzburg, Austria. Later, he became an inquisitor in Austria’s Tyrol region, Bohemia, Moravia, and Salzburg. However, he became notorious for his witch hunts.

Kramer began a crusade to stamp out what he said was a widespread problem of witchcraft. When he faced sharp criticism for his unjust and extreme persecutions, he decided he needed to put out a persuasive treatise on the subject. That’s when he collaborated with Sprenger and published Malleus Maleficarum.

Ultimately, Kramer, also known as Henricus Institor, said that he tried 100 witches and burned half of them to death.

By contrast, historians believe the co-author, Johann Sprenger, never tried any witches. He earned his Master in Theology degree, and in 1480, became the Dean of Faculty of Theology at the University of Cologne, Germany. In 1841, he received an appointment as an inquisitor.

Scholars debate Sprenger’s level of contribution to the text. They suggest that Kramer may have used Sprenger’s name and prestige to bolster the reputation of his book. If so, it is unlikely that he contributed much to the content.

Kramer’s Obsession with Women as Evil

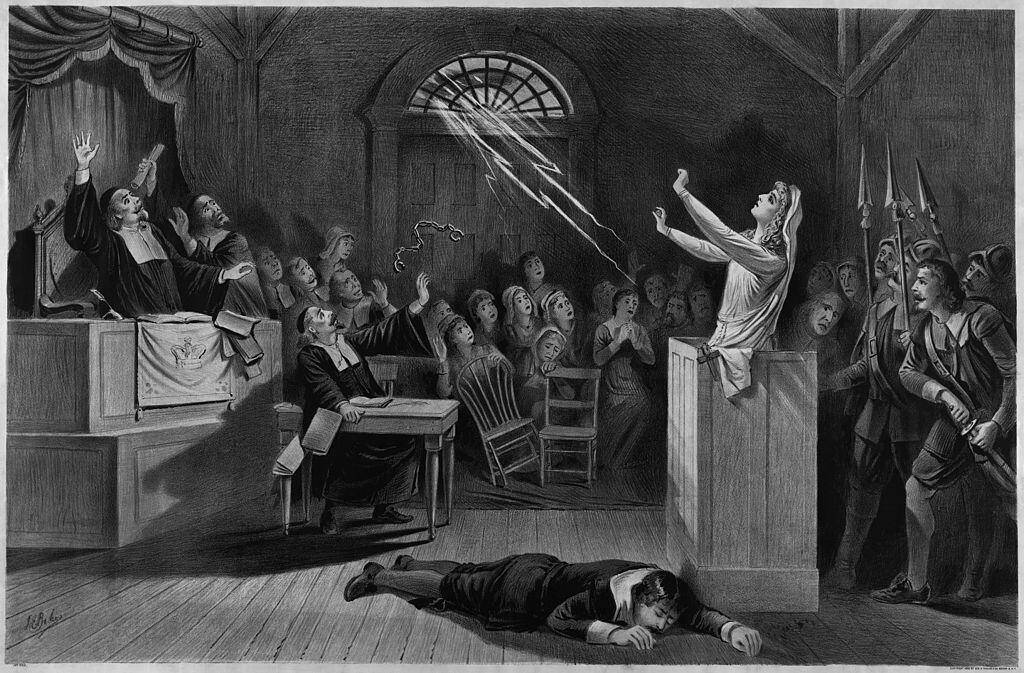

In the 16th and 17th centuries, authorities used the witch hunters’ handbook to justify unofficial kangaroo courts during a period of intense persecution of women who made up about 80 percent of those who faced execution for witchcraft.

Although Kramer did not exclude men as witches altogether, his book vilified women extensively. As such, many people believe that the author was waging war on women rather than witches. Indeed, his highly misogynistic attitude against women shines through in the Malleus Maleficarum:

- “They have slippery tongues, and are unable to conceal from the fellow-women those things which by evil arts they know; and, since they are weak, they find an easy and secret manner of vindicating themselves by witchcraft.

- She is more carnal than a man, as is clear from her many carnal abominations. . . . There was a defect in the formation of the first woman, since she was formed from a bent rib, that is, a rib of the breast, which is bent as it were in a contrary direction to a man. And since through this defect she is an imperfect animal, she always deceives.

- When she hates someone whom she formerly loved, then she seethes with anger and impatience in her whole soul, just as the tides of the sea are always heaving and boiling.”

Any woman was at risk of false accusations: those who were poverty-stricken or mentally ill, but primarily healers, herbalists, and “. . . specifically with regard to midwives, who surpass all others in wickedness” (Kramer, 1487). According to Kramer, midwives caused all problems with pregnancies. Moreover, he taught that they ate babies and offered them up to the devil at the time of their births.

Sex in the Hammer of Witches

Heinrich Kramer had a preoccupation with the sexual practices of the accused. The manual stated that women “know no moderation in goodness or vice” and “all witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable.”

According to the manual, women were lesser to men with an inherently evil nature. Only a woman such as the Virgin Mary, who Kramer idealized, could be all good. Most women were nothing more than temptresses and lustful, deceitful creatures filled with a propensity to copulate. Sexually immoral women were likely to be witches. He indicated that young girls are so lustful that the devil can quickly get them to do his bidding.

The Malleus Maleficarum accuses women of sexually consorting with incubi (male demons that have sex with sleeping women) and the devil — a relationship from which children can sometimes result. He states that demons can collect semen from one human and transfer it to another. He even questions whether a witch can be born of such a union.

One of the most bizarre claims Kramer put forth suggests that witches can put a glamour spell on a man that makes him think his penis has disappeared. While the devil can, in actuality, remove a man’s ‘member,’ the witch can only make a man believe under an illusion that his ‘member’ has left his body, according to the manual.

Witch Trial of Helena Scheuberin

One trial, in particular, is notable, for it led to the creation of the Malleus Maleficarum. In 1485, the trial of Helena Scheuberin took place in Innsbruck, Austria. People knew her as a strong independent woman who vocalized her feelings. When Heinrich Kramer went to Innsbruck to hunt for witches there, Scheuberin insulted Kramer, cursed him, and spat at his feet. She also called him a heretic for his diabolical acts against women and told people not to listen to his sermons about witch hunts.

The Lancashire witch trials in England resulted in the execution of ten people.

Kramer began an obsessive vendetta against Scheuberin and accused her of using witchcraft to kill a man. During the trial against her, Kramer questioned Scheuberin about lascivious sexual activities and attacked her virginal status. The Bishop Georg Golser said Kramer “presumed much that had not been proved” and kicked him out of town. Those trials in Innsbruck ended, but the disgrace prompted Kramer to write the incendiary Malleus Maleficarum.

Those Who Did Not Believe Were Heretics

Some Christian theologians and scholars denied the reality of witchcraft before the book came out. However, the witch-hunters’ manual taught that those individuals were heretics.

The ideas in the witch-hunter’s handbook took Biblical inspiration from Exodus, which says, “You shall not permit a sorceress to live.” If the Bible said there were witches, the Church considered it heresy if anyone denied their existence.

Persecution and Punishment for Heresy

Accusations of heresy could result in a trial and severe torture. Unfortunately, the Hammer of Witches quickly silenced the saner, more rational voices of the time who had argued against witch hunts. It could be disastrous for anyone to incite an inquisition. According to History.com:

“Those accused of heresy were forced to testify. If the heretic did not confess, torture and execution were inescapable. Heretics weren’t allowed to face accusers, received no counsel, and were often victims of false accusations. If the accused confessed before being tortured, punishments ranged from forced pilgrimages to whipping.”

Treatment of Women Suspected of Witchcraft

The witch hunters’ handbook prescribed that inquisitors should use various methods of torture upon a person suspected of witchcraft, depending upon the person. However, it did not indicate specifically what methods they should employ. While the individual awaited trial, she should remain in a cell, naked. Authorities should shave all the hair on her head and body.

Witch prickers were paid generously for finding witches.

Full body checks of women must take place in another room by honest women, who looked for items of witchcraft. Moreover, the person should suffer all forms of deprivation for prolonged periods, except for a small bit of bread and water. Accusers should make defendants believe that if they confessed, they would not face execution.

Influence of the Malleus Maleficarum

The Hammer of Witches was the most influential witch hunters’ handbook in history. As writer Shelly Barclay so eloquently put it, “To the modern eye, it [the handbook] is a horrifying lesson in misguided power, the danger of false religious superstitions and the dangers of allowing a single religious institution to control the well-being of the public. Through the 1600s, witch trials and executions continued in Europe and in North America. The famous Salem witch trials occurred between February 1692 and May 1693, where 200 people faced accusations of witchcraft and about 20 people hung at the gallows. The last person tried in Europe was Anna Göldi, who was beheaded on June 13, 1782, after she confessed under torture to entering into a pact with the devil.

References:

Hoffman, Whitney, and Stephanie Bortis. “Malleus Maleficarum (1486).” Malleus Maleficarum Index. Accessed April 7, 2020.

Kremmel, Laura. “The Witches Ordeal: The Treatment of Accused Witches in England.” Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Accessed April 7, 2020.

Hoffman, Whitney, and Stephanie Bortis. “The Witching Years: Demonology Fact or Faction.” Accessed April 7, 2020.

Stringer, Morgan L., “A War on Women? The Malleus Maleficarum and the Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe.” Oxford University. 2015. Accessed April 7, 2020.