Silbury Hill is a human-made hill in legendary Wiltshire County, England. A group of neolithic people constructed the hill between 2400 BC and 2300 BC. It is the largest prehistoric artificial mound in Europe.

Composition of Silbury Hill

Silbury Hill is composed of chalk, clay, gravel, and sarsen stones quarried from the surrounding area. The earliest sections of the hill contained preserved turf and moss. This discovery indicates that the area consisted of pasture when construction commenced.

Related: Stonehenge: A Megalithic Monument of Britain’s Ancient People

The site takes up about five acres, has a height of 40 meters, and a diameter of 167 meters. It may have been taller when built initially, possibly with a rounded top. However, local residents may have leveled the summit during the middle ages to construct a possible fortification.

Related: Woodhenge: Lesser Known Neighbor of Stonehenge

When Was it Built?

Estimates based on carbon dating of an antler found at Silbury Hill put construction between 2490 and 2340 BCE. The belief is that several communities added soil and chalk to the mound over time. Who built it and why is as big a mystery as Stonehenge, possibly even greater.

Winged ants were found inside of the hill. This indicates that construction began in August. This conclusion would have to take into account any climate changes and habit changes of these insects between then and now. Even if correct, it tells us very little.

Furthermore, we have no way of knowing if the time of year construction began was significant to these people. The lack of information prevents us from knowing who they were and if they possibly moved elsewhere to form another culture or simply died out over time.

A Phased Construction

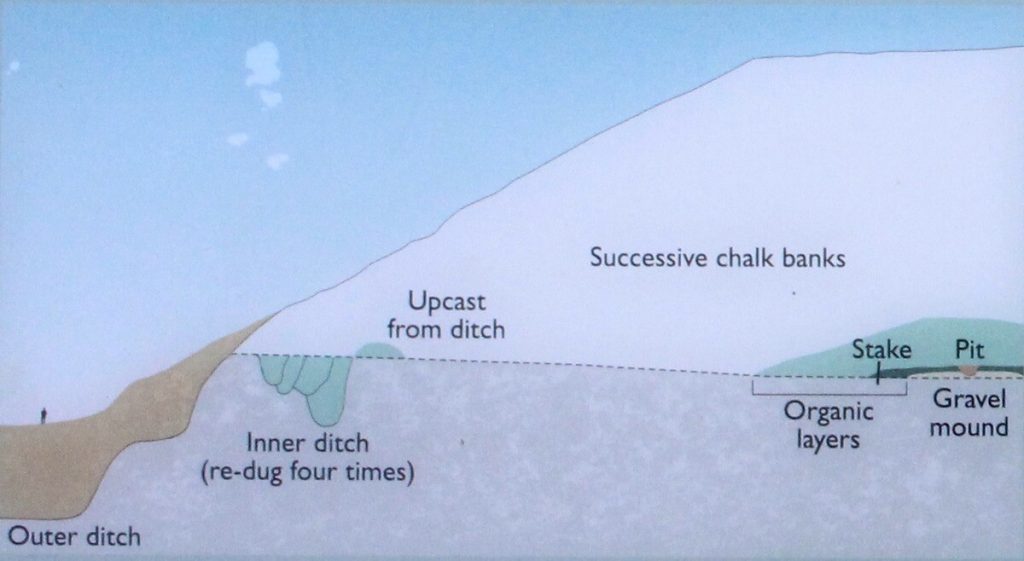

Building the hill occurred in three distinct phases:

- The builders first created a circular fence about 20 meters in diameter surrounding a well-trampled space. They added soil, gravel, clay, and turf to build a mound to 7 meters high. The diameter of the hill increased to 36 meters.

- The builders added chalk excavated from a quarry ditch nearby to the top of the mound. It increased the diameter to 73 meters.

- The third phase consisted of refilling the first ditch, then adding more chalk to the mound from a secondary ditch with a 100-meter diameter.

Construction of the mound required several generations to complete. Conservative estimates say it would have required hundreds of workers 15 years to build. Most agree the hill’s construction took about 100 years to complete.

We do not know if they eventually moved elsewhere or if they died off over time.

History and Rediscovery

A trench dug at the summit Silbury Hill revealed an antler. This find provided researchers an accurate carbon date. Estimates based on carbon dating results put construction between 2490 and 2340 BCE.

It lay abandoned for thousands of years after whoever built it decided to move on. We know the Romans discovered it sometime between the first and fourth century AD. A discovery in 2007 shows a Roman road clearly veers around the hill, and a Roman village lay at the hill’s base. Additionally, a Roman gold coin discovered in a mole hole on the summit is possibly from the Neronian period (54-68 AD).

The first mention of the site is a 1281 Assize Roll and referred to it as Seleburgh. The hill fell back into relative obscurity until rediscovered in the 17th century.

Writings from 1663 state:

“No history gives us any account of this hill. The tradition that King Sil (or Zel as the country folk pronounce it) was buried here on horseback and that the hill was raised whilst a posnet of milk was seething .”

John Aubrey (1626-1697)

Excavations

Archaeological digs at the site began by accident around 1723. Allegedly, someone at the summit started planting a tree and found a skeleton. Assuming this is true, it is likely that the burial took place following the mound’s construction and after its builders abandoned it. It is highly unlikely that the remains have anything to do with the construction of the hill. Later excavations indicate that it does not appear to be a burial mound at all.

At least six excavations are known. Some notable ones include:

– Edward Drax

In 1776, the Duke of Northumberland and Colonel Edward Drax tasked a group of miners to dig a vertical shaft from the hill’s peak. They failed to find any central burial location inside the mound.

– Reverend John Merewether

In 1849, Reverend John Merewether led a team from the Royal Archaeological Institute to dig a horizontal tunnel. They also failed to find a burial chamber but discovered undecayed moss, grass, and freshwater shells inside the mound’s center.

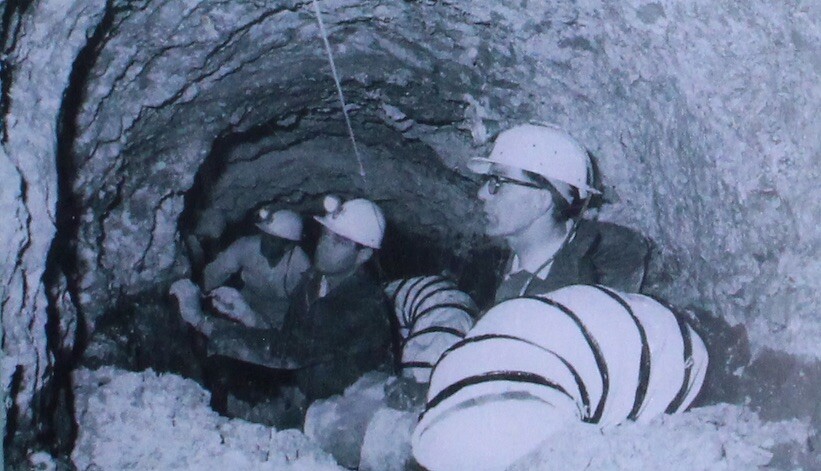

– Professor Richard Atkinson

Between 1968 and 1970, Richard Atkinson televised his archaeological excavation of the area on BBC. Millions of people tuned in to watch the program.

Damage and Restoration Projects

The early excavations not only turned up very little, but they also damaged the integrity of Silbury Hill. In 2000, heavy rains caused the 1776 Drax shaft to collapse, creating a hole at the summit. The tunnel also became unstable.

Between 2007-2009, English Heritage conducted conservation work on Silbury Hill to stabilize this national treasure.

So what have we been able to glean from Silbury Hill from the scant findings of the few digs conducted there?

The Mystery Endures

It is part of a landscape that boasts a Roman road, Stonehenge, and numerous other human-made features from long ago. Silbury Hill itself might be able to tell us a bit about the people who built it, but that is assuming any hypothesis about its purpose is verified.

Its height suggests its goal was to elevate something or someone. Perhaps a place for a ruling elite or a religious ceremony. Most experts agree it is not a burial chamber, but its exact purpose remains a mystery.

Cahokia Mounds: The Largest Ancient City in North America

There are very few clues. Nearly everything of significance obtained from the site comes from later cultures. All we know for sure is that its construction occurred a very long time ago and that it did not come to be there by accident.

Historic Mysteries updated this article on 6 October 2020.

Sources:

The Guardian Kennedy, Maev, retrieved 2/17/12.

The Telegraph, Watkins, Jack, retrieved 2/17/12.

Archaeological Investigation Report Series AI/22/ 2002

Royal Archaeological Institute