Tiamat, primordial goddess-monster of chaos, was the mother of the Babylonian pantheon. Her story has parallels in many later religions, most obviously in the Titans of Greek and later Roman mythos.

Tiamat is best known from Babylonian mythology, around the 9th century BC. However she she is also present in the Akkadian mythology which came before, which would make her very old indeed. Before all other developed religions, there were the Mesopotamian deities. And before them, according to their own mythology, there was Tiamat.

Tiamat may have given birth to the Babylonian pantheon, but she was not of them. She was a figure of chaos from before the gods, and her children were not also benevolent. She existed as a powerful figure outside the pantheon, but she was not above interfering in the affairs of the younger gods.

So it was with Tiamat’s monsters, fashioned to do battle with the Babylonian pantheon in their creation myth, known as Enûma Eliš. Tiamat herself would be killed in the upcoming conflict but her monstrous offspring survived to positions of prominence in the mythos.

Here are the eleven monstrous children of Tiamat.

1. Bašmu

Bašmu, the venomous serpent, took the form of an enormous horned snake with forearms and wings. In this monster we see the direct antecedent of the Greek hydra, with both even being represented by the same constellation in the night sky.

Described as a sea monster “sixty double-miles long”, its voracious appetite caused many problems and eventually the pantheon of younger gods sent Nergil, a snake charmer to subdue it. Fundamentally, Bašmu seems to represent the dangers of the sea, a common theme in myths from Poseidon to Jörmungandr.

2. Ušumgallu

Ušumgallu was a ferocious combination of a dragon, a lion and a demon, but it evolved to become much more in the Akkadian and later Babylonian myths. Its very name became associated with the divine as an honorific, and Marduk, father of the Mesopotamian gods and patron of Babylon itself, became known as ušumgal kališ parakkī, “peerless ruler of all the sanctuaries”.

In this we see a common theme in the fate of these monsters. Most became co-opted into service by the pantheon of gods, finding new meaning in the myths as useful deities and patrons of particular aspects of divinity.

3. Mušmaḫḫū

Another serpent (there are a lot of these in Mesopotamian myths), Mušmaḫḫū also has features of lions and birds. Here we have another hydra precursor, as Mušmaḫḫū seems to have had seven heads, just as with the monster slain by Hercules.

- Ugallu: Lion Headed God-Monster of Babylonian Life Insurance

- The Ogdoad: When Amun Ruled the Gods of Egypt

There is even a parallel to this exact story in the early Akkadian myths. Ninurta, a Sumerian warrior god (literally the “Lord of Barley”) is said to have defeated a seven headed serpent, and we even have a depiction of this, carved on a shell.

4. Mušḫuššu

The Mušḫuššu, the “furious snake” is another combination of animals, also having features of a lion, an eagle, horns and a crest. As the sacred animal of Marduk, many depictions of this monster survive and we can gain a fair idea of what the Babylonians thought Mušḫuššu looked like.

Most famously, Mušḫuššu is depicted on the 6th century BC Ishtar Gate which was once found in Babylon. This iconic blue gate contains depictions of many animals, but Mušḫuššu is included as the servant of Marduk.

5. Laḫmu

Now for a change of pace with Laḫmu, “the hairy one”, who is depicted somewhat straightforwardly as a man with a big beard. The extent of his humanity, and the reasons for him appearing as a man, are unclear, but it seems to have resulted in Laḫmu being seen as a heroic figure.

There were many Laḫmu in early Mesopotamian tradition, where they are associated with water and are invoked as a form of divine protection. It is only with the later Babylonian tradition that Laḫmu becomes the firstborn child of Tiamat, and a much more divine and cosmological being.

6. Ugallu

Ugallu, the “Big Weather Beast” (and personal favorite of this site) was a lion-headed god who found an entirely new niche beyond his first role in the Babylonian pantheon. Many amulets have been uncovered in the region, where Ugallu seems to have functioned as a talisman against danger.

The idea was that if you found yourself in danger and carried one of these talismans, Ugallu would appear to defend you. Given that Ugally was a massive, lion-headed monster, this could presumably come in handy, although actual evidence of this ever happening seems to be lacking.

7. Uridimmu

Uridimmu, the “Mad Dog” was a dog-headed humanoid figure who may date from as early as 1500 BC. He is apparently associated with rabid animals, and in appearance was intended to be portrayed as the opposite, and counterpart, to Ugallu.

- Animal Gods: The Ancient Egyptian and Hindu Pantheons

- Uruk, the First Great City: A Leap Forward for Humankind?

He is often carved into doorways as a trophy to ward off evil from entering the house, a talismanic presence in the same way as Ugallu. He is also associated with sickness and disease, and in later times a cult seems to have grown around him, lasting as late as the Persian Empire.

8. Girtablullû

Girtablullû has the head and arms of a man, but the body of a scorpion. First created by Tiamat, like the Laḫmu there were eventually many Girtablullû, and as with the other monsters they found a new role as servants of Shamash, the ancient Mesopotamian sun god.

In this role they appear in the Epic of Gilgamesh, where they guard the gates of Shamash at the great cedar-covered mountain of Mashu. Gilgamesh passes the gate and through the tunnel, arriving at the ancient Mesopotamian underworld of Kumugi.

9. Umū dabrūtu

The monster of violent storms, we don’t even know what Umū dabrūtu looked like as nothing has survived, although the safe money is on another composite figure with lions, eagles, bulls, snakes and dogs in the mix. However we do know the fate of Umū dabrūtu: broken by Marduk, like the others this monster was forced into the service of Babylon.

These monsters, once defeated, became apotropaic symbols, that is guardians against misfortune and wholly benevolent to the Babylonians. Presumably the presence of Umū dabrūtu offered protection against bad weather.

10. Kulullû

A fish-man hybrid, Kulullû resembles a Mesopotamian merman and, apparently because of his association with good fortune and prosperity, became an enduring figure in the Babylonian mythos, with numerous depictions surviving. In fact, the Kulullû is the earliest depiction of a merman of which we are aware.

Kulullû appears everywhere, in palace frescos and boundary stones marking the limits of ancient Babylonia, with many figurines of the monster also surviving. Again there are eventually multiple Kulullû, and in later myths there are even fish women as well.

11. Kusarikku

The last of Tiamat’s eleven monsters is the Kusarikku, the bull-men and obvious precursors to the Minotaur of Greek myth. However these monsters had the arms, torso and head of a human and the ears, horns and lower parts of a bull.

In later myths, once broken by Marduk Kusarikku became associated the sun god Shamash in his role as the god of justice, one of two of Tiamat’s monsters who serve this god specifically, along with Girtablullû. He is even mentioned in a song designed to sooth a crying child.

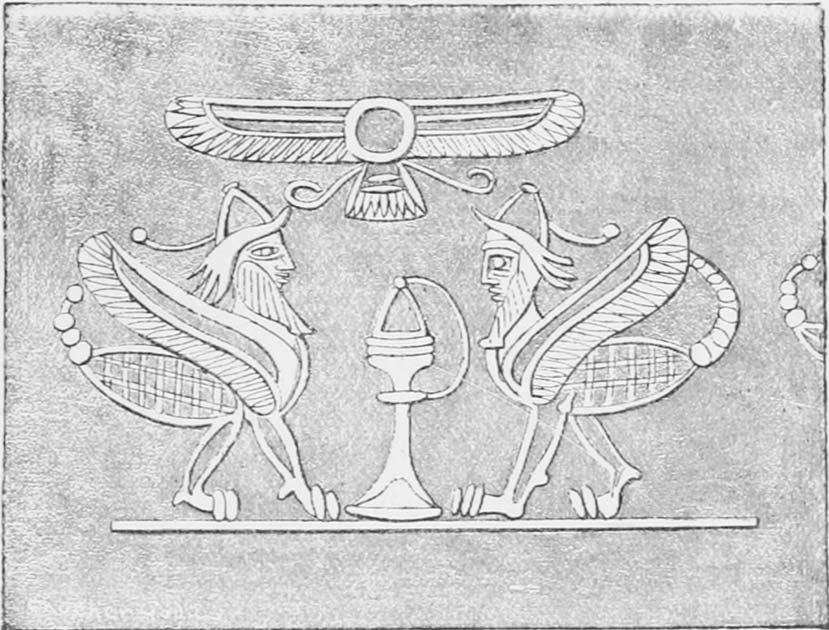

Top Image: Marduk, on the right fights Tiamat. His conquering of the eleven monsters she birthed forms the Babylonian creation myth. Source: Roberto.Amerighi / Public Domain.

By Joseph Green