There are many memoirs, poems, and newspaper articles that bring to life the horror of World War I and the disfigurement that this conflict brought about. However, particularly in Britain, this crucial topic was seldom shown visually in a widespread media outlet.

The horror and trauma that the veterans of the war faced were not limited to their actual injury but the isolation and loss of humanity that they experienced on their return home with their injuries. This was especially true of those with facial injuries.

That was until Francis Derwent Wood founded the Tin Noses Shop to help the soldiers cover their injuries through technical skill and artistic talent.

The Great War

World War I brought about disfigurement and mutilation on the battlefields around Europe to a scale that had not been experienced before. It has been estimated that approximately 60,500 soldiers from Britain alone experienced head or eye injuries, whilst 40,000 had to have one or more limbs amputated. Between 1917 and 1925, 11,000 operations were performed on servicemen that had experienced disfigurement.

One reason that explains the high number of head injuries was not because there had been a huge improvement in sharpshooting on either side, but that the soldiers were unused to trench warfare. Trench Warfare was a relatively new tactic that had only begun to flourish in the late 19th century.

The American surgeon Fred Albee claimed that the soldiers thought they could “pop their heads over a trench and move quickly enough to dodge the bullet”. The revolution of the machine gun and new heavy artillery proved to be the winner when it came to speed, however.

The sheer amount of injuries and the damage that they had wrought upon the soldiers led to a huge uptake in facial reconstruction and plastic surgery. Across Europe in France, London, and Belgium facial surgeons became huge commodities. This was the beginning of the Tin Noses Shop, known officially as the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department.

Recreating Appearances

Sculptor Francis Derwent Wood brought the idea of portrait masks up when in joined the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1915, as an orderly at the London General Hospital in Wandsworth. Wood began by revolutionizing the plaster and splits department and gained the support of his commanding officer for his idea to make metal masks for the heavily disfigured soldiers.

The plan was to meticulously recreate the original appearance of the soldier from their surviving features and old photographs. 3 sculptors, a casting specialist, and a plaster mold-maker were all recruited by Wood.

Francis gave an interview in 1917 for The Lancet in which he said that his work “begins where the work of the surgeon ends. When the surgeon has done all he can to restore functions … I endeavor to employ the skill I happen to possess as a sculptor to make a man’s face”.

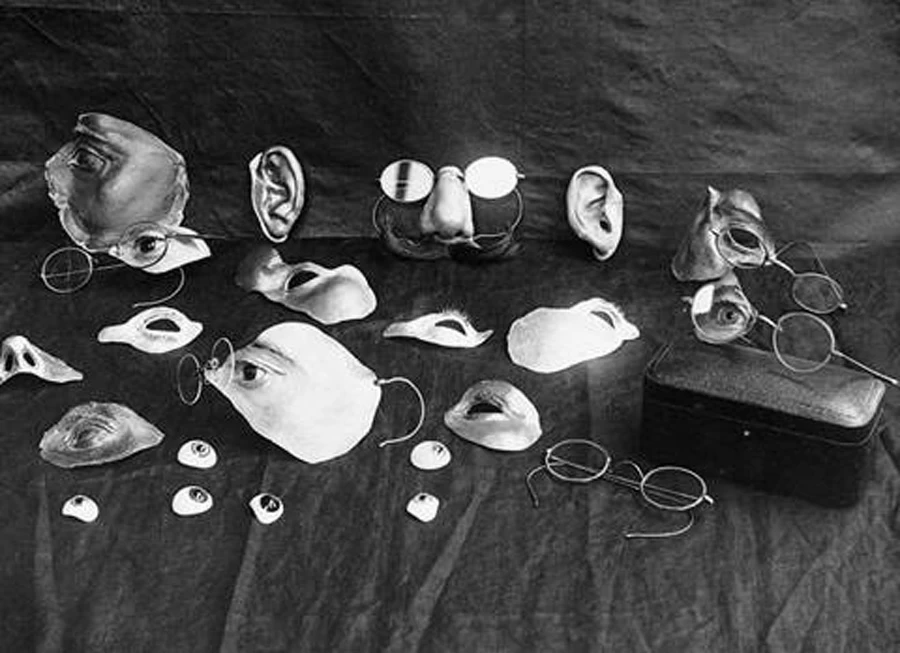

The mask-making process was a long and arduous one. It began with a plaster cast of the face and then a clay squeeze would be taken to reflect the healed face and missing features. He could do this with all features of the face, be it eye sockets, cheeks, noses, or jaws.

The mask itself would be made from copper approximately 1/32 inches (0.8mm) thick, created from a final plaster cast which was coated in silver and painted to match the skin color. Wood would then seek to match not only the color and complexion but also the texture of the face as well.

Francis would painstakingly recreate features that had been lost such as eyebrows and eyelashes. He would paint on individual hairs for the eyebrows and use very thin metallic foil, cut into strips which he tinted and coiled for eyelashes.

Despite his huge amount of effort to create a realistic and seamless repair to the soldier’s face, he had not thought about comfort and there were many reports of the masks being uncomfortable to wear. This led to a paradox for the soldiers. The masks granted them the freedom to integrate back into society and yet were a constant and aching reminder of all that they had lost.

What Remains?

None of the masks that still exist today are from Wood’s organization in London. Instead, the rare few that do exist come from Anna Coleman Ladd, an American sculptor who was working in Paris. She is known to have created 185 masks by the end of 1919 inspired by Wood’s work. His department, unfortunately, was disbanded in 1919 and thus his work was ended.

It remains unknown whether the masks were thrown away due to their uncomfortableness, both physically and mentally, or whether the masks remained buried with their owners. This is not implausible as the family of the deceased may have wanted to avoid looking at a soldier’s wounds in the event of an open casket.

It may also be that the masks merely acted as a go-between for surgeries. It allowed the soldiers to feel normal and walk around without being gawked at.

A Necessary Innovation?

It has been argued by historians and psychologists that trauma to the face of soldiers created an environment of dehumanization. The face is something that all people gravitate towards. It helps people understand more when they can see a person’s face.

However, the damage done to the male appearance in the post-World War I world has remained largely absent from the discussions around the conflict. It was a huge part of the war, and disfigured veterans faced an entirely new battlefield when they returned home.

Innovators such as Francis Derwent Wood and Anna Coleman Ladd were hugely influential in this period. Their combination of art and medicine was able to create hope in even the most traumatic cases.

The art of the masks provided the soldiers with the ability to overcome the loss of identity that followed the injuries that they sustained. The impact of the prosthetics in allowing wounded servicemen back into society should not be discounted.

Top Image: Captain Francis Derwent Wood and one of his patients. Source: Horace Nicholls / Public Domain.

By Kurt Readman