In the 17th and 18th centuries, there was no centralized response from the state to tackle the social problem of mental illness. This would not come into effect until the 19th century.

This led to the rise in private “madhouses” that sprung up around Britain, on an unprecedented scale compared to anywhere else around the world. There are only sparse mentions in the 17th century but by the 19th century there are large amounts of evidence for the so-called “trade in lunacy”.

By 1724, there were around fifteen operating in and around the London area. But what was this trade and how did the world go from madhouses to psychiatric care for those with mental illness?

History of Lunatic Asylums

To understand the care for the mentally unwell, it is necessary to go far from 19th century Britain. In the Islamic world of previous centuries, the hospitals there were described by European travelers as a place of kindness and care, especially for those who were suffering from mental illness.

A hospital was built in Cairo in 872, by Ahmad ibn Tulun which used musical therapy to aid in the care of the insane. However, historians have warned that medieval Islamic hospitals were not as ideal as they sounded.

In Europe, only a small amount of those who were considered as “mad” were housed in an institutional setting. Often those who were considered mentally ill were held in cages or kept within cells in the city walls.

Worse than that, some were kept as an amusement for the nobles and royal court. There was some care for the insane in the monasteries while others, particularly in Germany, were kept in “fools’ towers”. In Paris, there were a small number of cells kept in the Hotel-Dieu for those who were clinically insane.

After the Christian Reconquista, in Spain, a few institutions were set up in hospitals across the country such as in Valencia, Barcelona, Seville, and Toledo. In England, the Priory of Saint Mary of Bethlehem, later known as Bedlam, was founded in 1247. At its formation, it housed around six men.

Public Asylums

Even by the 18th century, there was little in terms of institutional provision of care for those classed as mad. It was seen as a domestic problem. This meant that families and local parishes were deemed as the ones who were to take care of those who suffered.

Outdoor relief was sometimes extended by the Parish authorities to families and some financial support was given when families could not care for their suffering family members. However, there was no wider help offered to assist the patients.

One thing that could also happen was that those who were deemed to be financially untenable may be boarded out to others in the community. There were also exceptions made for those who were judged to be disturbing and violent. Parish authorities may even put up the money for the costs of confinement in charitable asylums or workhouses.

Private Asylums

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the model of care changed. It still required that the patient had money. The number of private madhouses steadily increased throughout these centuries.

This period is known as the “trade in lunacy”. The madhouses operated on a profit basis within the free market economy. Many were run by laypeople, but others were run by medical professionals. Examples include Thomas Arnold at Belle Grove Asylum in Leicester and Nathaniel Cotton in St Albans.

In 1792, Samuel Newington founded Ticehurst House in East Sussex. This was a premium asylum in which patients were allowed to live in separate villas around the grounds. If they had the money, they were allowed to bring their own cooks.

Patients here were predominately from the wealthiest in society. On the other side of the spectrum, Hoxton House became renowned for where patients had to share beds due to the overcrowding of the private asylum.

Because of the differing standards of care for those who were suffering, legislation was introduced to regulate the industry in 1774. In England and Wales, all asylums had to be licensed by magistrates and had to have annual licenses.

These could only be renewed by providing accurate admission registers and proving that they have been properly maintained. Outside of the capital, Justices of the Peace visited the asylums accompanied by medical practitioners.

Additionally, the patients were also required to have medical certification. This gave a little bit of protection for those people who were seen to be an inconvenience to their families. There was a worrying trend of families incarcerating those family members in madhouses and calling them insane.

Poor Patients

This did not mean that the poorer members of society were completely abandoned to their madness. Private asylums did accept the poorer sufferers of mental illness.

Their costs were still covered by local parishes or by the poor law union which had incarcerated them. By 1800, there were around 50 private licensed asylums in England, the majority of which allowed for private and poor patients. It led to a national concern for the lack of public asylums.

In 1808, legislation was passed to encourage counties to build lunatic asylums for the poorer members of society. Most counties however were not thrilled about establishing new institutions because of the large financial burden that these facilities would cost.

There was little funding provided for the counties to do this from the government. Large areas of the country went without public asylums and so parishes continued to be relied upon to accommodate the poor and mentally ill.

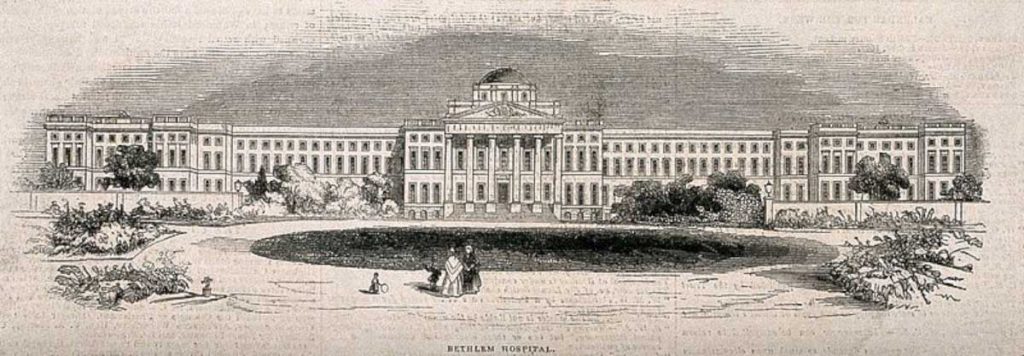

There were many scandals between 1814-1819. They often included the neglect of poor patients and mistreatment. Places like York Asylum and Bethlem Hospital became terrible perpetrators of this.

Further legislation was passed in the 1820s which created the Commissioners in Lunacy in London before it was rolled out to the rest of the country by 1828 and in Wales in 1844. Inspectors visited premises that were housing the mentally ill, both private and public without notice.

This would allow them to see a true picture of how these facilities were run. The inspectors had the power to withdraw licenses and prosecute the owners of the establishments.

Top Image: Francisco de Goya’s Madhouse starkly shows the fate of poor mental patients, but richer ones could enjoy a better standard of care as the “Trade in Lunacy” was found to be profitable. Source: Francisco de Goya / Public Domain.

By Kurt Readman