The Tulsa Race Massacre was a white supremacist terrorist massacre that lasted two days, May 31 through June 1, 1921, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. At the time of the massacre, Oklahoma was still a relatively new state operating in post-Civil War America.

Oklahoma became a state on November 16, 1907, and almost immediately, the state passed segregation laws that separated trains by race and set voter registration rules to disenfranchise the African American population in the state. Legally no one who was black could serve on a jury, and they couldn’t hold a public office, even at the local level.

The law was white, the juries were white, and the Klu Klux Klan was on the rise. In 1915 local chapters of the KKK began to grow across the US, and by the end of 1921, “3,200 of Tulsa’s 72,000 residents were Klan members.”

Lynchings were fairly common across the state, but what made Tulsa unique was its large population of professional, educated, and affluent African Americans. This led to a thriving “black district” that was booming while the white part of Tulsa was less prosperous.

Black Wall Street

The segregated district of Tulsa was known as Greenwood, and due to how successful this district was, it earned the name “The Black Wall Street.” What made Greenwood so exceptional was that the African American residents built their own businesses and provided services to the other black residents.

Greenwood has several grocery stores, two movie theaters, multiple churches, a hospital, and two newspapers. The residents of Greenwood were clergymen, lawyers, doctors, dentists, and accomplished black professionals. Greenwood was a perfect example of black excellence in a time when racial tension in the US left many African Americans in deplorable social and financial positions.

But all this would come tumbling down on Memorial Day weekend, 1921. A misunderstanding and vigilante justice caused the Tulsa race massacre. Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old black shoeshiner, was arrested for allegedly assaulting 17-year-old white elevator operator Sarah Page.

Dick’s boss had arranged for his black employees to be permitted to use the “colored restroom” on the top floor of the Drexel Building next to the shoeshine parlor. On the day that started it all, a clerk at a clothing store on the first floor of the Drexel Building reported hearing a young woman scream and seeing a young black man running out of the building.

The store clerk ran to the elevator and saw Page in “a distressed state”. The clerk assumed that the black man had sexually assaulted the young lady, and called the police.

While the clerk assumed Page had been raped, there are many explanations for what likely happened. The most commonly believed theory is that since Rowland would need to use the elevator to get to the restroom, he and Page probably recognized or knew each other.

It is suggested that Rowland likely tripped getting into the elevator and, while attempting to catch himself as he fell, grabbed Page’s arm, making her scream. There is no written statement from Page taken by the police, but she was said to have told the police that she hadn’t been raped and that when Roland suddenly grabbed onto her arm, she got startled and screamed; she did not intend to press charges.

- The Battle of Blair Mountain: Unleashing the Workers’ Revolution

- Knights of the Golden Circle: A Pro-Slavery Empire

Rowland fled because he knew that the store clerk or any other white person who heard Page scream would assume he did something to hurt her. Black men accused of sexually assaulting a white woman were instantly targets for lynch mobs.

On the morning of May 31, Rowland was arrested and taken to Tulsa city jail for questioning about the alleged assault. The police commissioner at the time said he received an anonymous call that threatened Rowland’s life.

Rowland was moved to a more secure jail on the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse. Many lawyers at the courthouse recognized Rowland from having their shoes shined by him, and witnesses said they heard several white attorneys say about Roland, “Why, I know that boy, and have known him a good while. That’s [the assault] not in him.”

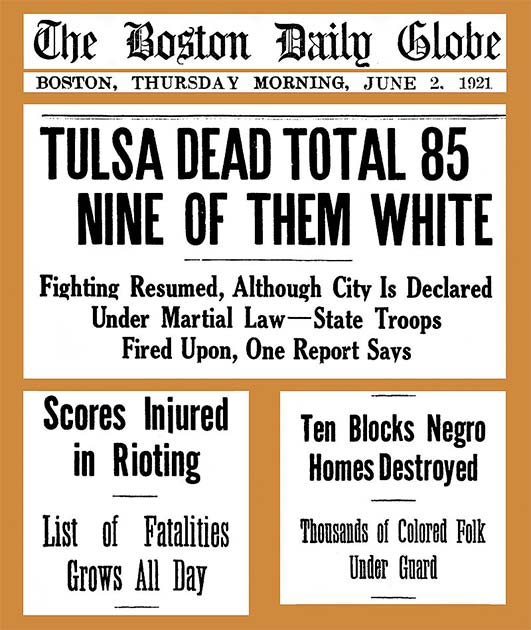

The Article

One of the white-owned newspapers in Tulsa published an article about Rowland’s arrest and gave it the damming headline “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator,” which described the alleged sexual assault.

Now here is the start of a lot of “missing evidence” in the case of the Tulsa Race Massacre. Some witnesses claim they saw the same edition of the newspaper that had a warning of a potential lynching of Rowland with the title “To Lynch Negro Tonight.”

All original copies of the newspaper with the lynching tonight headline have never been found, and the microfilm of the original paper is missing that page. The newspaper went out to the public around 3 pm, and by 4 pm, white Tulsans began to gather near the Courthouse.

By sundown, there were hundreds of white Tulsans gathered around the Courthouse and had the look of a lynch mob. The newly elected sheriff of Tulsan County, Willard McCullogh, constantly told the white mob to go home and to protect Rowland; the sheriff set 6 armed officers up around the building with commands to shoot anyone who tried to intrude, no questions asked.

Across the track in Greenwood, the town’s black residents were trying to figure out how to prevent what looked like a quickly impending lynch mob from killing Rowland. Once again, there is a lot of conflicting information about the Tulsa race massacre, but somehow, a group of around 60 black men armed with guns arrived at the Jail to defend Rowland and support the sheriff.

When the white men saw the approaching armed black men, an estimated 1,000 white people ran home to get their guns and returned to the courthouse, ready to fight. When the shooting began is murky, but most reports state that the first shot was fired by black store owners who came out of their ships to defend a black man who six white men were beating up.

Once the first shot rang out, all hell broke loose. Both sides, the white people and the terrified black people, began shooting at each other and traveling down the streets in town. White mob members broke into stores to steal weapons, pushing the black residents deeper into Greenwood.

A movie had just finished playing at a Greenwood theatre, and as the viewers headed out onto the street, they were greeted by a mob of potentially 2,000 armed and angry white men shooting in every direction, and the crowd went running resulting in even more chaos and confusion. The fighting started around 10 pm, and by 1 am, things got really bad.

Black Wall Street Burns

White mobs began to set black-owned businesses in Greenwood on fire. The white men would loot and trash the stores before lighting them on fire.

- The Tuskegee Experiment: Killing For Science?

- Hoovervilles: American Shanty Towns from a Hundred Years Ago

When Greenwood residents began to wake in response to the gunshots, fires, and screaming, some residents grabbed weapons and went to defend their district while hundreds of other black residents fled the city in fear for their lives. The National Guard was called in, but the police department and local “citizen militias” decided to deputize and arm random white men, which was the worst thing that could have happened. These new deputies did not operate within the law and encouraged the slayings.

The white-armed lynch mob began robbing and burning the homes of African Americans; the hospital was burnt to the ground, and churches went up in smoke. At 9:15 am on June 1, 1921, three companies from the National Guard arrived in Tulsa, and the general of the Oklahoma national guard declared martial law. By noon most of the fighting was stopped.

It is believed that thousands of black residents had escaped the city, about 4,000 people were arrested and placed in multiple detention centers, and around 10,000 Greenwood residents had been impacted by the Tulsa race massacre. The exact number of deaths was minimized, and newspapers across the country reported that between 36-176 people (mostly African Americans) were murdered.

A 2001 Commission into the riots estimated the number of deaths might have been closer to 100-300. Injured white residents were taken to hospitals, but since the only hospital in Greenwood was destroyed, the Red Cross quickly came in to help.

The Red Cross reported 183 people were hospitalized in Greenwood with gunshot wounds and burns, and 50-300 people were believed to have died. The exact number of victims of the Tulsa race massacre is unknown because the truth was not reported due to racism and mass graves were allegedly created, and black deceased victims were dumped in and buried without getting their names or a head count.

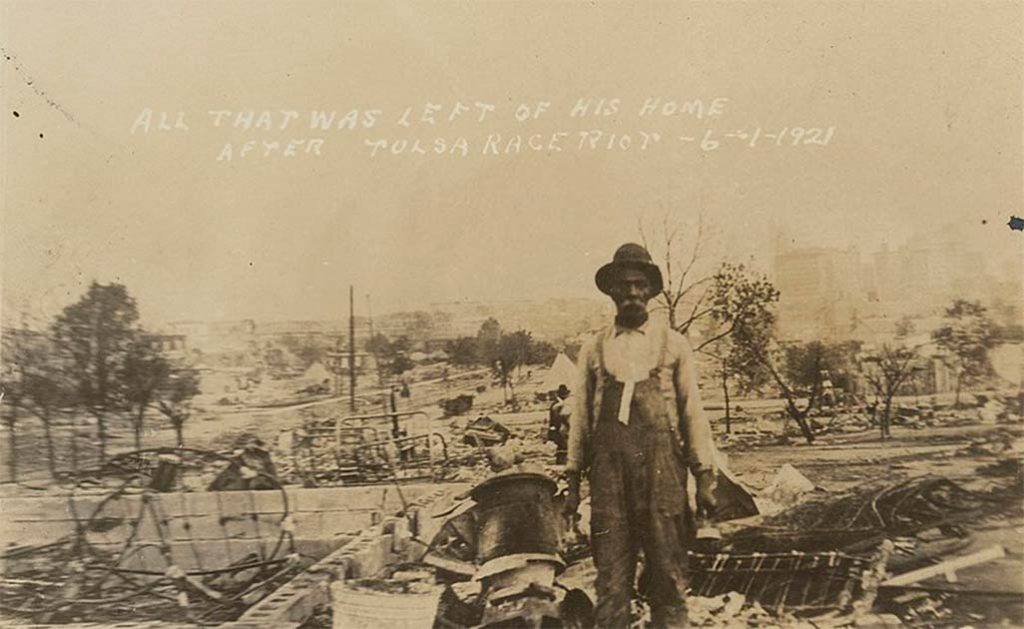

Thousands of Greenwood residents lost their homes, businesses, and livelihoods and were forced to live in tents. Greenwood reported the destruction of 191 businesses, the only black hospital in the city, many churches were turned into smoldering ash, 1,256 homes were burnt to their foundations, and an additional 215 homes were looted.

By December 1921, the Red Cross reported that an estimated 10,000 people were left homeless. In the months following the Tulsa race massacre, nobody was arrested for their role in the massacre or the destruction of Greenwood. In fact, white city planners wanted to turn the now empty land in Greenwood into a commercial district, pushing the black Tulsans further out of their city and taking their land.

The Tulsa race massacre was intentionally omitted from local and state history, and many people in Oklahoma had no idea about the brutal events of May 31 and June 1, 1921. In 1996, 75 years later, a state commission was created to investigate the massacre. In 2001 the commission suggested the following restitutions be made to black residents:

- Direct payment of reparations to the living survivors of the 1921 Tulsa race riot;

- Direct payment of reparations to descendants of the survivors of the Tulsa race riot;

- A scholarship fund available to students affected by the Tulsa race riot;

- Establishment of an economic development enterprise zone in the historic area of the Greenwood district; and

- A memorial for the reburial of the remains of the victims of the Tulsa race riot.

The restitution efforts came 80 years too late, and the 118 known living survivors of the Tulsa race massacre were given gold medals, which, again, did not make up for the injustices of the massacre.

While restitution is a tricky subject in any situation, the one benefit of the nightmare of the massacre was that in Oklahoma, it is now a mandatory part of the state’s education system students are now educated about the Tulsa race massacre, the devastating results of the event, and the impact on the black residents of Oklahoma.

While the events of the past can not be changed or paid off by the government, the only way to prevent situations like the Tulsa race massacre from ever happening again is through talking about what happened, educating students and the public, and continuing to strive for racial equality in the United States. If nobody forgets, then everyone must remember. Everyone needs to remember what a devastating impact racism has had on history.

Top Image: Homes of the African American community in Tulsa on fire during the Tulsa Race Massacre. Source: US Library of Congress / Public Domain.