The story of the Donner Party is one of struggle, family ties, survival, and tragedy. While the story is partly that of an amazing journey, it is remembered for a gruesome detail, one that disgusts at the same time that it fascinates. It is said that through one of the most extreme tales of survival in American history, the Donner Party had to resort to extreme measures to survive, though many did not survive. It is said that they ate their dead.

The Donner Party was a group of 87 emigrants who set forth in a wagon train for California. The core group left Independence, Missouri in May of 1846. They picked up many more along the way. The group is named for its leader — George Donner. George and his brother Jacob’s family made up 16 of the travelers.

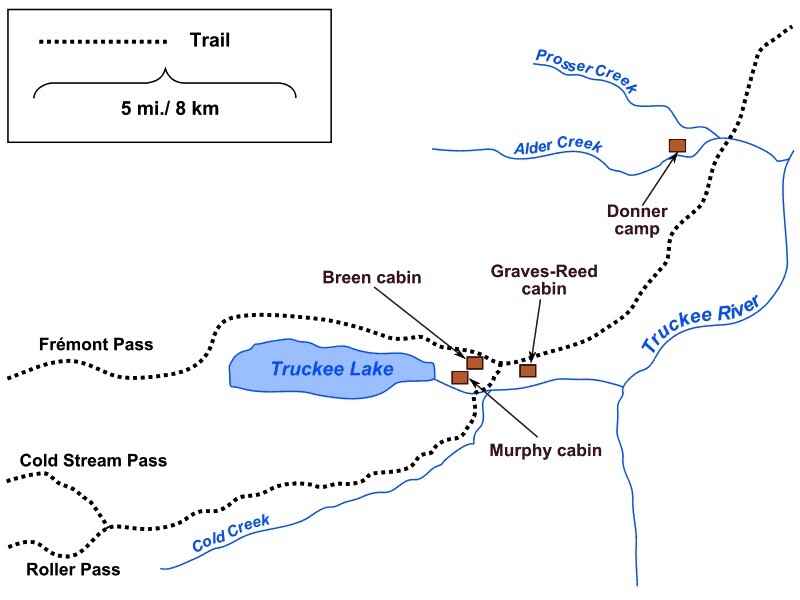

Donner Party Map

Before the month of their departure was even out, the Donner Party lost its first pioneer. An older woman died of natural causes and was buried along the way. Another four would die before the grisliest part of the Donner Party tale. The going was not easy for this wagon train. Even without later events, one could say that this group did not have luck on their side.

You May Also Like: Sawney Bean: The Scottish Clan of Cannibals

Traveling through the wilderness with livestock, people and goods was not exactly a walk in the park in the mid-nineteenth century. However, it was done with great success and the westward push went down in history. The Donner Party had it even harder due to a mistake. George Donner took the party through the Great Salt Lake Basin, thanks to advice from “The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California” by Lansford Hastings. Hastings Cutoff was the name of the shortcut. Hastings himself had never taken a wagon through the area and probably should not have suggested that such groups go that route. Doing so was ill-advised. They went off the main route in southwestern Wyoming. They then went through Utah and part of Nevada on the cutoff. It took them through the desert and added at least one month to their trip thanks to wagons sinking in the sand, water shortages, etc.

By the time the Donner Party had made it through the cutoff, they had lost numerous cattle to Native American theft and killing. They had used up many of their supplies. The men were also tired from hacking their way through the rough terrain of the cutoff. Everyone was on edge. There was fighting, alleged theft, accusations, and one elderly man was even left by the side of the trail to die. This was the situation before the worst of their troubles began.

Because of their perils, the Donner Party was in the Sierra Nevada Mountains when they should have already been in California. They knew that snow would come, but believed they had roughly three weeks until the pass was impossible to navigate. They were wrong. Because they had split up along the journey for numerous reasons, 60 pioneers set up at Truckee Lake (Donner Lake) in three cabins that were already located there, while the Donners set up at Alder Creek in tents. They would be unable to leave for several months. The snow kept coming until it was more than 20 feet deep.

Over the months from November to about April, when the entire party and then just those who had yet to be rescued remained, one of the saddest stories to come out of the westward expansion unfolded. First, they ate what little livestock remained. They traveled between the two camps when possible and there was some sharing, but there was very little to share. There was some hunting when possible, but it is almost certain that they had to resort to eating rodents and family pets before long. It is natural to shudder at the thought, but considering that these people were boiling leather and softening bones to eat, it is understandable. They were cold, starving, and trapped.

During their ordeal, a group of men and women went out on snowshoes they fabricated from their supplies. They were going to try to get help and bring it back to the camps. Unfortunately, the “Forlorn Hope,” as they came to be known, wound up worse off for their trouble. The detachment of 15 pioneers became lost. Only seven lived and the story has it that they lived by eating their dead. There were no murders.

Stories from rescuers and allegedly some Donner Party members later stated that there was pretty rampant cannibalism near the end of their stay in the prison of snow. Nearly half of the Donner Party died from malnutrition, infection and other ailments. Of those people, about 21 of them are thought to have been eaten, though none of the eaten were murdered.

Evidence for Donner Party cannibalism includes the abovementioned witness and a journal entry by Patrick Breen dated February 26, 1847. In this entry, Patrick mentions that Mrs. Murphy was talking about eating the dead, but that he did not think she had done it. He also mentioned that the Donners were talking about eating their dead and that he assumed they had done so by the time of his writing. This, and the testimony of rescuers that they had seen severed body parts when they reached the Donner Party, are the best evidence for cannibalism we have.

There is some evidence to the contrary of cannibalism. A group of anthropologists studied the bones found in the cooking fire of the campsite at the creek and found no human bones. Many take this to mean that there was no cannibalism. However, it is important to remember that the Alder Creek Camp was only one portion of the Donner Party. There were the temporary camps of the “Forlorn Hope” party and the three cabins on the lake. There is also the fact that the human bones may not have been cooked in the hearth the way the animal bones were cooked.

You May Also Like: The First Thanksgiving: What was it Really Like for the Pilgrims?

From a perspective of documentation, the Donner Party was forced to cannibalize some of their deceased family and friends. There is no concrete evidence to support this, but there is the fact that they were starving. Patrick Breen had no reason to make up stories about people thinking about eating other people in his situation. He did not state it happened outright, but they were there for several more weeks after that entry. The party had to eat something or die. It seems highly likely that some of them went for the only food source that was left, as so often happens in survival situations where there is no food.

Sources

Trails to Utah and the Pacific: Diaries and Letters, 1846-1869, retrieved 4/14/12, loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/connections/trails/thinking5.html

No Evidence For Donner Party Cannibalism, Anthropologists Say, Science20, retrieved 4/14/12.