A new weapon was discovered in 1942: napalm. This indiscriminate and deadly fire has been used to annihilate civilizations by engulfing them in flaming destruction.

Despite the innovation of this kind of combat, the usage of fire in conflict dates back to ancient times. Incendiary devices have their roots in the utilization of sulphur, charcoal, blazing arrows, and perhaps most enigmatically, something called “Greek Fire”.

Greek fire survives only in descriptions of its destructive potential, and it seems it was a deadly weapon of war indeed. But what makes Greek Fire so unique is that even to this day its composition remains a secret, one which apparently died with the Byzantine Empire which created it, and which it helped protect

Napalm of the Ancients

By the end of the 7th century the Arab kingdoms of the east had slowly but surely began to take over the Christian Mediterranean. Having already conquered areas of the North Africa coast, Sicily, and the iconic fortress island of Rhodes, their eyes were firmly set on the Byzantine Empire, and its near mythical capital of Constantinople.

They began by using their naval fleet to capture an island that lay across the sea from Constantinople, known today as Istanbul. From here they mounted a four-year long siege, slowly crippling the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Constantinople was known as the “God protected city” and was in desperate need of a miracle. But when one came, it was not from God but from a man named Kallinikos.

A Greek speaking Jewish refugee who had escaped Muslim-held Syria in 668 AD, Kallinikos of Heliopolis had seen the devastation that flammable mixtures could cause. He created a concoction that would self-ignite and could be sprayed from tubes at approaching enemy ships, this would later be dubbed “Greek Fire” by the crusaders.

This explosive concoction was a godsend as it helped the Christians keep a firm hold of their territories, successfully fending off the Arabs and halting their advance. Years later, the same strategy would be applied to thwart another Arab onslaught.

An Ancient Flamethrower?

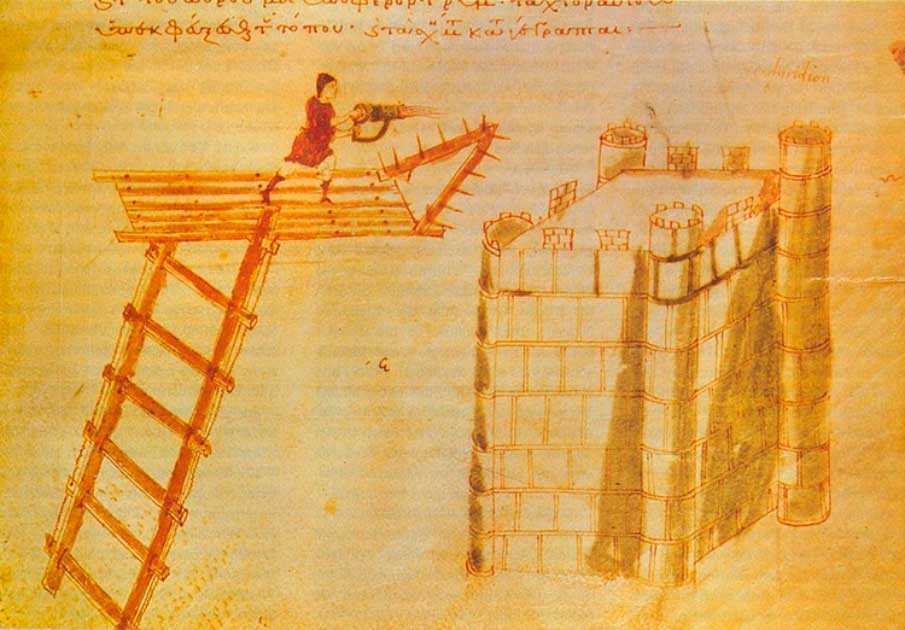

For Greek Fire to be effective it needed not just the right composition, but a working delivery system as well. Fast sailing ships called “dromon” were used to carry the flammable concoction, and in order to propel the mixture bronze tubes were attached to syphoned pumps, mounted onto the Greek naval ships like large hoses. Once within range the mixture was sprayed on the decks of their enemies’ ships.

- Archimedes’s Weapons of War: Embellished Stories or Deadly Devices?

- The Nazi V-3 Cannon: Could this “Vengeance” Weapon Have Destroyed London?

The effectiveness of the Greek Fire was indisputable as it would ignite anything it touched, and once alight there was no known way to quench the blaze. Many armies tried and failed miserably to resist the Greek weapon. When covering their ships in animal-soaked hides failed, the enemies of Constantinople were forced to maintain a distance out of reach of the flamethrowers, but this meant they also weren’t in range to attack themselves in any but the clearest weather.

As Greek Fire could not be quashed with water, fleets that were exposed these ancient flamethrowers were quickly engulfed by the flames, leaving those onboard no option but to jump overboard or risk being roasted to death.

An Un-Decipherable Formula

Greek Fire’s chemical composition, about which there is still no unambiguous consensus, was what made it so powerful. This was obvious a closely guarded state secret, and this secrecy has doubtless contributed to the loss of the formula. However, there have been three interesting hypotheses.

The first was based on reports of “thunder and smoke” that followed the discharge which led scientists to conclude saltpeter, an early type of gunpowder, was involved. Since saltpeter was not used in European warfare until the 13th century, this was later determined to be impossible.

Since the fire was not extinguished by water a some theorized that quicklime was one of the main components in the mixture. Quicklime was commonplace amongst the Arabs and in the Byzantine Empire, but unlike Greek Fire it needed water to ignite. According to reports Greek fire was sprayed straight on the decks of the enemy ships without interacting with water. So, this theory too was doused.

The most plausible explanation is that Greeks used naphtha, also known as crude oil or petroleum today, to make fire because they had easy access to it from the Black Sea or the Middle East. A few decades later, in the heat of combat, the Abbasid armies of the Arabic dynasty would fill tiny copper pots with flaming naphtha: did they learn of its usefulness from the Greeks?

It is obvious that producing this mixture was a risky task given how volatile the mixture was. Many of the enemies of the Byzantines lacked access to or knowledge of the sophisticated technology required to safely distil the petroleum. We even have reports of the Bulgars gaining possession of the formula and firing mechanism, but we are told they were unsure of how to use the highly developed weapon.

Greek Fire for a Lasting Byzantine Empire?

After its first use in 673 AD the Byzantines knew they had struck gold, but crucially they realized that if they wanted to maintain this upper hand their secret formula must remain top secret. Over the next seven centuries Greek Fire was employed many times to stave off foreign invaders.

- Fireships in the Night: How was the Spanish Armada Defeated?

- The Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane: The First Cruise Missile?

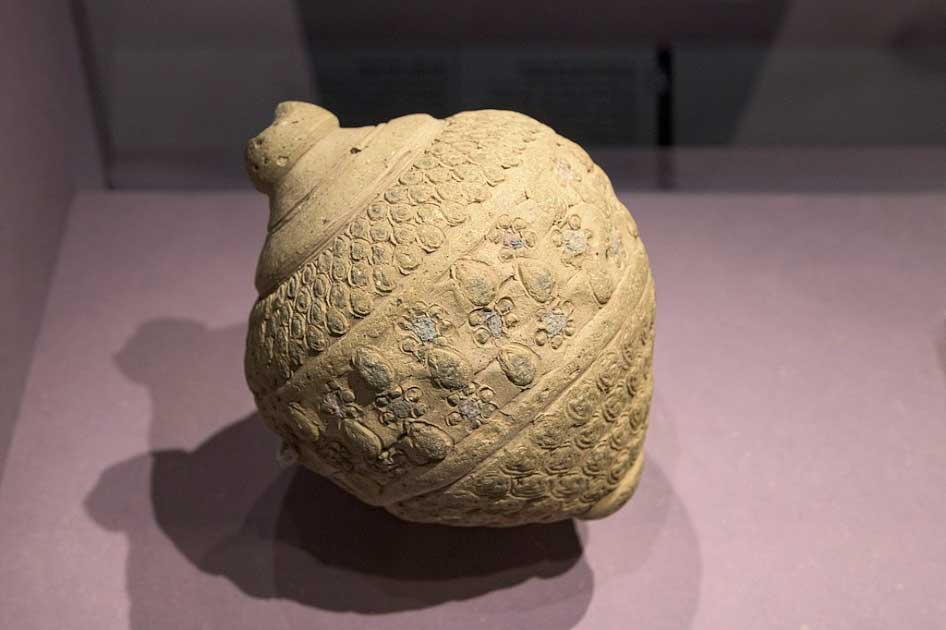

Leo II of the Isaurians, in the interior of what is now Turkey, once more employed it against the Arab assailants in 717 AD. In 972 AD, John I Tzimisces gave the command to create clay grenades that contained the flaming formula and which were covered in wet bales. With his troops and Greek Fire grenades ready, he marched to the Russian-captured city of Preslave, won the conflict, and freed the Bulgar ruler.

Greek Fire was an invincible weapon for centuries, and Romaus I Lecapenus, who used it to battle the Russians in the 10th century, understood its value. Three things, according to him, must remain out of foreign hands in order to preserve the Byzantine Empire.

The first was the Byzantine imperial regalia. As a part of the Holy Roman Empire, these relics preserved the Byzantine Empire’s history and founding principles. The second was any princess of the realm, and he considered the empire’s future in jeopardy if a princess travels abroad. And the third was Greek Fire.

The first two were occasionally entrusted to foreign rulers and allies, but the third was never given to outsiders. Greek fire’s significance in Byzantine history, according to English historian John Julius Norwich, cannot be overstated. According to popular belief, the Byzantine Empire’s survival and longevity were due to this special elixir and the secrecy of its composition.

Fading into History

Greek fire progressively lost its place as the pre-eminent weapon of the age over the centuries of its use. Reading between the lines one could surmise from its applications and characteristics that a few unfavorable circumstances started to compromise this once-magical weapon.

It required a calm sea to aid the pumps and to ensure accurate aiming, as well as favorable winds because if the wind was blowing away from the Byzantines, they would run the risk of igniting their own fleet. A further problem would have been the restricted range; once the opponents learned the maximum range, they could adjust and take this into consideration. Finally, as technology developed with time, more effective and efficient forms of combat were created.

Without a doubt, Kallinikos and his creation of Greek fire are major contributors to the long-lasting Byzantine Empire that we know of today. What Greek fire was comprised of and how it was created are still mysteries. And imagine how history, and perhaps even the nature of our current world, would have changed if Greek Fire had not been invented and the Byzantine Empire had been destroyed by Arabia.

Top image: Greek Fire was employed as a naval flamethrower, lighting fires that could not be put out. Source: Unknown Author / Public Domain.

By Roisin Everard