Many people across the globe believe in things they cannot see. Whether these be invisible gods, luck or fate, these supernatural forces continue to show their influence, from individuals right up to the fabric of society.

One such belief in the invisible, and one with surprisingly persuasive evidence, is that of ley lines. These hidden paths form a grid across the Earth, connecting the sacred places in a web of straight lines which covers the entire planet.

In this way ley lines are surprisingly inclusive, connecting the sacred and crucial sites of ancient worship across the planet. Landmarks such as the Egyptian Pyramids, the Great Wall of China, Stonehenge, and others have been found to fall on ley lines.

Given the lack coordinated communication between the cultures that built these sites, this poses a dilemma. Is it possible that the ancient people were aware of earth energies in choosing their holy places? Is it possible that they were able to sense that the Earth’s energies were stronger around these ley lines?

Or is this all a form of confirmation bias, where researchers have drawn enough straight lines on the map to confuse random chance with significance?

The Theory of Ley Lines

The concept of ley lines is surprisingly recent given the sites being referenced, being first theorized in detail in 1921. Since that time, the debate has never been concluded, and the arguments continue over whether they exist or not.

Indeed, many of the proponents of ley lines confess they do not understand their purpose in detail. Most conclude that these lines represent areas of natural power, with the intersections being particularly potent. But how this manifests, and how this can be useful, are a mystery.

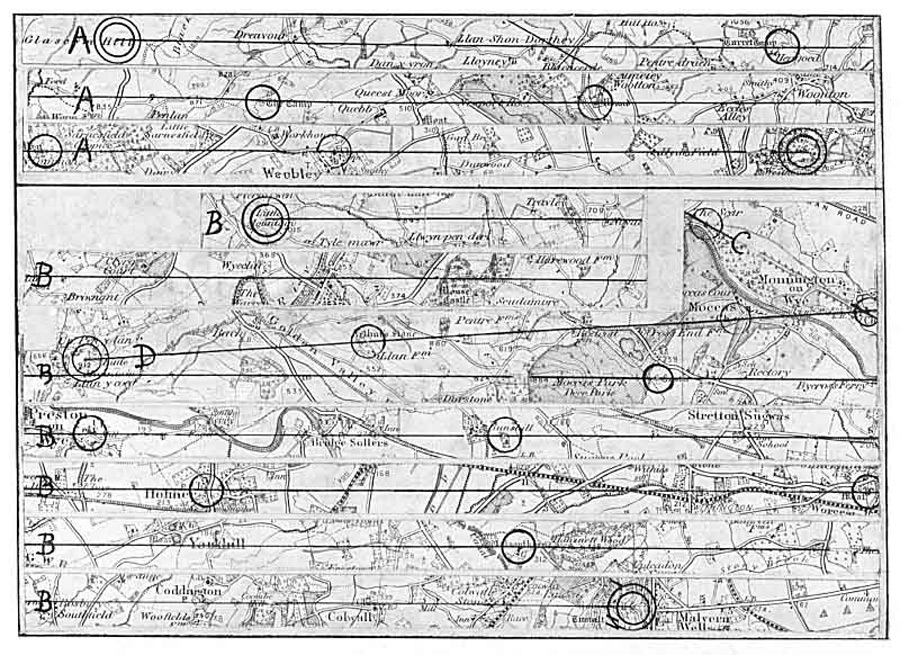

In the year 1921, an archaeologist named Alfred Watkins made a controversial observation. Watkins claimed that dozens of famous ancient sites, situated at different points across the globe, can be shown to have been constructed in a series of straight lines.

Irrespective of whether the sites were man-made or natural, they somehow fell into this pattern, in a series of what he called “ley lines.” With this theory, he created a concept whereby some natural force from the Earth was being made manifest in the positioning of these features.

Just like lines of longitude and latitude, these lines crisscross the globe. Natural formations, monuments, and even rivers follow these paths, and are therefore supposed to possess some form of supernatural energy.

Examples

Alfred Watkins offered evidence for his theory by giving examples of different types of monuments in a straight line across the globe. He drew a straight line across southern England, and later one from the southern tip of Ireland to Israel, which he claimed connected seven different locations that included the name “Michael,” in some form. And it was termed as “St. Michaels Ley Line.”

The lines are easily proven to anyone with access to a map, but this is clearly insufficient evidence. On the same map one may draw any number of lines connecting sites, mistaking the chance arrangement for a supernatural force guiding construction. Ritual sites with a shared alignment, such as solstice temples, would further reinforce this appearance.

Similarly, many structures which would appear significant do not appear on these lines, and are discounted. These unanswered problems have led to many questioning the concept since 1921. Many researchers believe these alignments as just a coincidental overlapping, a similar illusion to seeing faces or animals in clouds.

But still, there are many fans of the supernatural and science fiction who believe in the existence of ley lines. Moreover, this theory is yet to be practically proved or disproved, but the found evidence and connecting lines across the maps may yet prove its existence.

A Practical Application?

One of the more down to earth theories about ley lines relates to their use as a technique for navigation. They have been theorized as a tool by which early British (ley lines were, initially, a very British concept) travelers could guide themselves safely to their destination.

Early overland navigation would have been accomplished by a traveler marking a distant high point, such as a mountain, monument, or other prominent feature, and using it as a landmark to navigate towards. Intervening sites would be built along this route, enhancing the appearance of a hidden path.

Today, there are pieces of evidence that suggest the existence of such trackways in Britain. Not just that, but these trackways connect sites of immediate use to the traveler, such as water sources, churches, and castles. But a common criticism on the ley lines is that, as there are many given points over an Earth map, a straight line can be possibly drawn through any of the two points, in some order.

Alfred Watkins supported this concept but believed that these chosen routes were already in place, and that early navigation may have been guided by supernatural forces. He also noted the commonality of alignment in areas of ritual significance.

Watkins’s theory was based upon the thinking of an astronomer named Norman Lockyer. Lockyer had studied the respective alignments of ancient European monumental architecture in sites such as Stonehenge, hoping to uncover the astronomical relationship between the ancient structures.

Unknown and Unproven

Most of the papers and books are published so far across the globe, relating to Watkins’s concept of ley lines, reject and criticize the supernatural aspect of his theories. But this theory has evidently caught the attention of the modern age and the counterculture movements.

Many, unsatisfied with the explanations for the universe offered by science, believe that these mysterious lines have some spiritual enlightenment, energy fields, and cosmic power in them. What this means, and what the impact could be, has yet to be agreed upon.

Are these just established routes across the countryside used by early travelers? Are they real at all, or just a coincidence of constructions? Many continue to believe in the power of ley lines, and, for the moment, all that can be said is that nothing has been proven, either way.

Top Image: The network of ley lines connect ancient sites across the globe. Source: Newland Aerial / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri