Our sky is dominated by the moon, the second brightest object we can see. Reams of poetry have been written about it, blame assigned for everything from woman’s suffrage upsetting the chauvinist applecart, to lycanthropy and madness.

The moon is fascinating, magical, mystical and above all, singular. However if you were to as someone from a thousand years ago about that last point, you might have received a confusing answer.

At least that’s what a group of monks recorded in 1178, the year the moon, according to them, split in two. Of course, they were mistaken but the event has intrigued modern astronomers and historians for decades and we are still uncovering new clues and theories about what may have caused this mysterious lunar phenomenon.

So, what really happened in 1178, and did these monks believe the moon had split in two?

What Happened to the Moon in 1178?

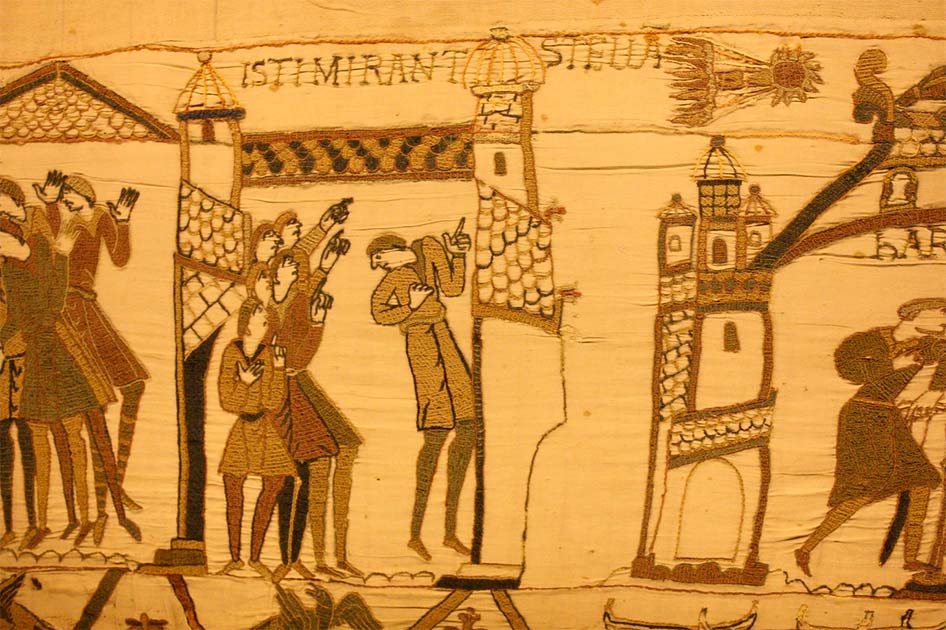

On June 18, 1178, a group of 5 monks from Canterbury, England observed something that blew their minds. They believed they had witnessed the moon splitting in two. They recorded their description of the event in a manuscript called the Gesta Stephani, written by the monk Gervase of Canterbury.

Gervase recorded how around 9 pm that night the moon was waxing gibbous (meaning it was approaching a full moon, but not quite) when several monks saw “the upper horn [of the moon] split in two”.

Gervase described how a flaming torch appeared to crash into the moon, causing a bright light and plume of smoke. This smoke remained visible for quite some time after the impact.

The event sounds pretty impressive but did the monks really think the moon had split in two? It should have become apparent pretty quickly that the moon was still in one piece. If they didn’t really think the moon had split in two, why did they describe it this way?

Well, it’s possible that the description was a simple result of the limitations of language and understanding at the time, as well as the difficulty of observing celestial objects without modern technology. It could be that the monks didn’t understand what they were seeing and lacked the terminology and knowledge to accurately describe it.

It’s also been suggested that the monks witnessed a meteorite impact that caused a large plume of debris and dust to rise from the surface of the moon, which could have appeared to the observers as if the upper portion of the moon had split in two. If the impact had been large enough to cause a seismic event or series of events, it might have caused the moon’s surface to shift or crack, creating the illusion of a split.

It could also have been a case of good old-fashioned religious superstition. It’s a group of medieval monks. Of course, they saw a glowing light in the sky and made it sound like the moon was splitting in two. They were probably disappointed when the world didn’t end.

Finding Answers

It should come as no surprise then that the moon didn’t split in two at 9 pm on June 18, 1178. If it had, you’d expect more than one historical reference to it. That begs the question, what really happened that night?

Well, Gervase’s description of the event remained almost completely forgotten until a geophysicist at the State University of New York, Jack B. Hartung, stumbled across it in 1976. The conviction with which it had been written struck Hartung and he decided to investigate further.

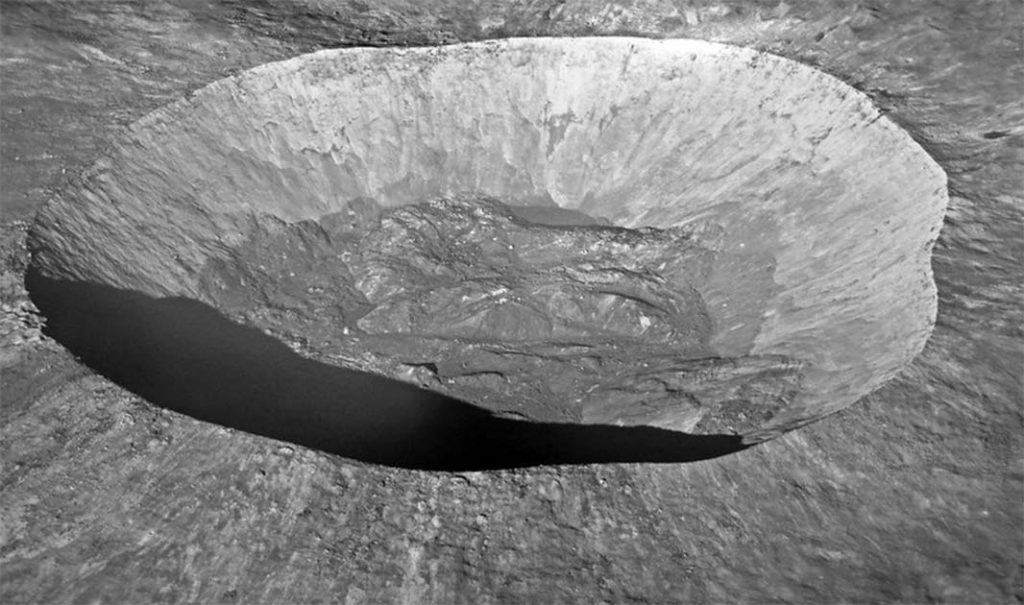

He theorized that the event the monk was describing was a massive impact on the lunar surface. On the moon is a 22-kilometer (13.6 miles) crater which is roughly where Gervase described the moon splitting.

Hartung examined high-resolution images of the crater which had been taken by the Apollo missions and observed that the long bright radial marks created during the crater’s formation had not yet been erased by lunar dust. He deduced that the crater was a relatively recent one.

So, in Hartung’s mind, the location and time of formation lined up with the events of 1178. The only problem was probability. Hartung recognized that the chances of the moon experiencing an impact on such a scale throughout recorded human history was about one in a thousand. Hartung’s theory quickly became controversial.

Some astronomers, like Odile Calame and John D. Mulholland, backed Hartung after reviewing new images which had been taken by the Soviet probe Luna 24. These images appeared to agree with his hypothesis, even if they didn’t prove it outright.

Others weren’t convinced and said that the crater’s formation wouldn’t have created the same phenomena the monks described. The monks had more likely seen a meteorite entering the earth’s atmosphere.

- Tabby’s Star: Deep Space Mystery Never Seen Before

- Outrageous Astronomy – Who Was Behind The Great Moon Hoax of 1835?

However, in the last fifteen years or so the theory has been almost entirely disproven. In 2009 an astronomer by the name of Tomokatsu Morota calculated that the crater was actually at least one million years old, and possibly as old as ten million years.

In 2012 the cosmologist Jorg Fritz went even further. He estimated the crater was around 1 million years old but added that if the crater was only 800 years old the earth would still be being pelted with a rain of lunar rocks from the collision. The crater would also be showing elevated temperatures, which haven’t been observed by any lunar mission.

The strongest argument against Hartung’s theory came back in 2001 though. A graduate student called Paul Withers at the University of Arizona worked out that an impact that large would have caused ten million tons of lunar material to be sent in the direction of Earth.

This would have caused around 100,000 shooting stars per hour. Everyone around the world would have seen an event of this scale, not just the 5 monks in Canterbury.

So, what did they see? The answer lays in the fact that so few people saw it. Many astronomers, like Withers; believe the monks were just at the right place at the right time. They saw a meteor that was directly in front of the moon and heading straight at them.

This meteor was coming at the right angle for the monks to believe it was splitting the moon in two. It would have been large enough to cause the illusion but small enough to simply burn up in the earth’s atmosphere.

Or there is another option. It never happened at all. Withers pointed out in his study that on June 18, 1178, the crescent moon wasn’t even visible in Canterbury. While Withers charitably put this down to the date being wrong, Peter Nockolds, a historian of astronomy had other ideas.

According to him, Gervase’s account is pure fantasy. The monk had a record of ascribing strange celestial apparitions to Christian victories in the Crusades. As such there is a good chance the event never happened, and it was a case of Gervase recording propagandistic symbology.

The truth is we’ll probably never know the truth. All we know for sure is that the moon didn’t actually split in two. The answer seems to be either the monks saw a meteor coming straight at them, or never saw anything at all.

Top Image: The monks were convinced the Moon had spit in two: did they think they were witnessing the Apocalypse? Source: Oveco / Public Domain.