You know you are real. “Cogito, ergo sum” as the man said, “I think, therefore I am”. Or at least, therefore you are, for you can be sure you think. The problem is, you cannot be sure anyone else thinks, or even that anyone else exists.

This is the problem of solipsism, that only one’s own mind is certain to exist, which therefore throws all conventional notions of objective truth and external existence out of the window. This philosophical quandary has intrigued thinkers for centuries, inspiring profound reflections on consciousness, perception, and the boundaries of human knowledge.

How can you be sure that anyone apart from you is real? We could all be automatons, functionally indistinguishable from other people because of course, the very idea of “other people” might itself be false. We could look like you, act like you, talk and behave as you would expect others like you to behave. But that doesn’t guarantee we aren’t all pretending.

For that matter, how do we know that any of what you perceive is as it really is? What guarantee do you have that the world (and the wider universe) around you is not just some gloss applied by your brain to an entirely different reality?

What objective evidence do we have of anything, really? We only know what we perceive, and we have no way of checking if what we perceive is objectively true.

A Very Lonely Existence

Solipsism is the philosophical idea that the only thing a person can be truly sure of is the existence of their own thoughts and consciousness. When one accepts this perspective, all external phenomena, everything we see, hear, and interact with becomes uncertain and potentially illusory. In essence, the only thing a person can be sure of is that they exist, nothing else.

The idea comes from the inherent limitations of human perception and the subjective nature of our experiences. Descartes, the 17th-century French philosopher summed it up best with his axiom, “Cogito, ergo sum” (I think, therefore I am). This emphasizes the undeniable certainty of self-awareness while casting doubt on the external world’s reality.

Solipsism challenges conventional notions of knowledge and truth, prompting individuals to confront the possibility that their entire reality may be a construct of their mind. It raises profound questions about the nature of perception, consciousness, and the boundaries of human understanding.

While solipsism may initially seem intellectually isolating, it pushes you towards some profoundly deep philosophical questions about reality and existence. Yet, grappling with the problem of solipsism can lead to profound existential uncertainty and a sense of profound isolation in a seemingly solitary universe.

- Roko’s Basilisk: A Dangerous Thought about Deadly AI

- Spooky Action at a Distance: Quantum Entanglement and FTL Communication

The origins of solipsism can arguably be traced back to the ancient Greek sophist Gorgias (483-375 BC) who wrote, “Nothing exists. Even if something exists, nothing can be known about it. Even if something could be known about it, knowledge about it cannot be communicated to others.” Other ancient thinkers also pondered the nature of consciousness and our awareness of the world, but it wasn’t until much later that this branch of thought got its own name.

The modern form of solipsism finds its roots in the skepticism of early modern thinkers like Rene Descartes. His famous declaration underscored the undeniable certainty of self-awareness while casting doubt on the reliability of sensory perception and the existence of an external world.

The idea then gained further traction during the 18th and 19th centuries as German idealism began to emerge, particularly in the works of philosophers like George Berkeley and Immanuel Kant. Berkeley posited that reality exists only in the perceptions of individual minds, suggesting that the external world is dependent on human perception for its existence.

The 20th century witnessed a resurgence of interest in solipsism, fueled by developments in existentialism and analytic philosophy. Existentialist thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger grappled with questions of individual existence and subjective experience, challenging traditional notions of objective reality.

Meanwhile, analytic philosophers like Ludwig Wittgenstein and Bertrand Russell explored the limitations of language and logical reasoning in addressing philosophical quandaries, including solipsism. But facing a problem, and solving it, are two very different things.

The Impossible Problem

While very few philosophers have genuinely claimed to believe in solipsism, it remains a popular thought experiment because of its fundamental inscrutability. Despite centuries of inquiry and debate, scholars have yet to definitively resolve this enigma, primarily because of several inherent challenges.

The reasons why solipsism is said to be impossible to prove can get overly complicated and migraine-inducing. However, in its simplest form, solipsism is tough to solve because it questions whether anything outside of your own mind is real.

Since it’s based on your thoughts and perceptions, proving or disproving it gets tricky. Plus, if you try to prove it using your senses or logic, you end up in a loop, using your mind to prove your mind exists. This makes it really hard to find a solid answer, leaving us with more questions than solutions.

Further complicating things is the fact the thinker can’t rely on others to help them. Why? Because their fellow philosophers could just be figments of the thinker’s imagination conjured up by their own mind.

Moreover, the problem of solipsism intersects with broader epistemological debates about the nature and limits of human knowledge. Even if one were to accept the existence of an external world, questions inevitably arise regarding the reliability of sensory perception. Essentially, how do we know that the world we perceive is the same as the same someone else experiences and isn’t being warped by our own perceptions?

Ultimately, the problem of solipsism at best defies easy resolution, and at worst cannot be resolved. The only way to answer solipsism once and for all would be to read to another person’s mind, and even that only gets us part of the way there.

Since it is currently impossible to read someone else’s mind, it is impossible to prove that other minds exist. Even if one were able to read someone else’s mind, it would be through the filter of one’s mind (which was doing the reading). This argument makes solipsism impossible to “solve” and makes its circular logic painful to think about for too long.

OK, so?

The problem of solipsism has spurred a whole host of spin-off philosophical responses and theories about the universe, each offering distinct perspectives on the nature of reality and human existence.

- The Phlogiston Theory and Caloric, the Fluid that Transferred Heat

- Is The Matrix Real and Not Just a Movie?

One response to solipsism is epistemological skepticism. This is a school of thought that calls into question the possibility of attaining certain knowledge about the external world. This skeptical stance acknowledges the limitations of human perception and cognition, highlighting the inherent uncertainty that pervades our understanding of reality. But accepting a problem, as mentioned, is not a solution, merely a surrender.

Another theory that emerges from solipsistic inquiries is philosophical idealism. This asserts that reality is fundamentally mental or conceptual in nature. Proponents of idealism contend that the external world is a product of consciousness, suggesting that physical phenomena are ultimately manifestations of mental states or ideas. Great, but that gets us no further towards an objective reality.

Some philosophers advocate for pragmatic approaches to solipsism, emphasizing the importance of practical engagement with the world despite epistemological uncertainties. Pragmatism encourages individuals to focus on meaningful actions and experiences rather than getting bogged down in abstract metaphysical speculation. It is arguably the healthiest reaction to solipsism: get over it and don’t overthink things.

And then you have existentialist thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger who explore the implications of solipsism for human existence. Existentialism emphasizes individual freedom, responsibility, and the subjective experience of being-in-the-world.

By confronting the existential implications of solipsism, existentialist philosophy encourages individuals to embrace the uncertainty of existence and create meaning in an inherently ambiguous universe.

Finally you have the moral nihilists. Solipsism also intersects with moral philosophy, leading some to embrace moral nihilism, the belief that moral values and principles lack objective validity. Think of it as playing a video game within which you make “good” or “bad” decisions: since it is only a video game, you can roleplay whichever you like in the interest of a fuller gaming experience.

So it is with our “reality”. From a solipsistic perspective, moral nihilism follows logically if one accepts the premise that reality is ultimately subjective and reliant upon individual consciousness. Without an objective foundation for morality, moral nihilists argue that ethical judgments are ultimately arbitrary or illusory.

This is the most dangerous aspect of solipsism: the belief that if nothing truly exists there are no real consequences and moral judgments are a waste of time. How can murder be wrong if you can’t be sure other people even exist? Who are others to judge you if they are just figments of your own imagination?

Conclusion

So maybe don’t embrace the last one. But the problem remains: solipsism’s enduring mystery challenges our understanding of reality and consciousness. From ancient roots to modern interpretations, it prompts deep philosophical reflection.

Despite its unsolved nature, solipsism invites us to confront the limits of knowledge and find meaning amidst uncertainty. Cogito ergo sum, and that’s all we can say for sure.

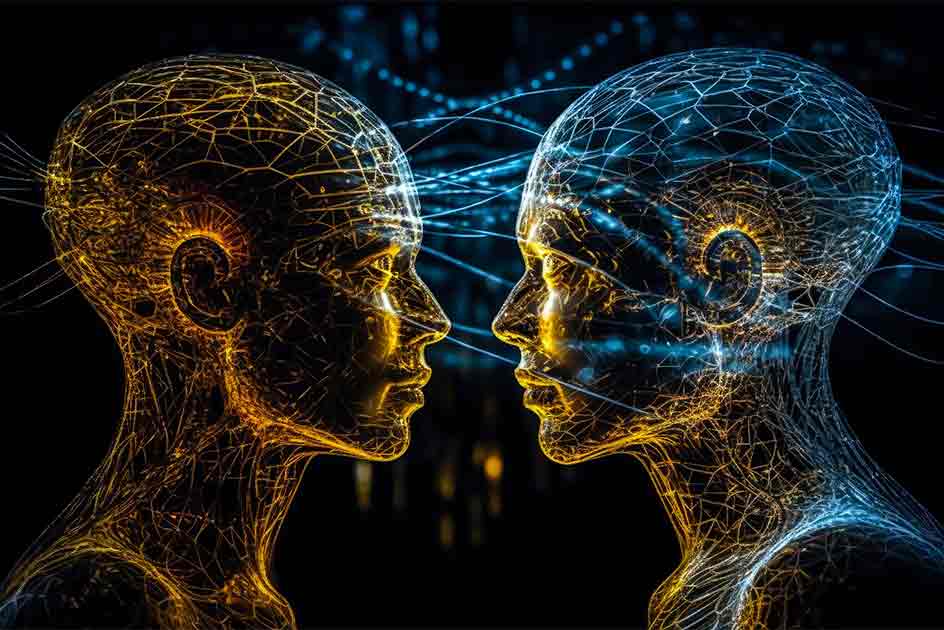

Top Image: Solipsism notes that we cannot distinguish objective reality from our subjective experience of it, and that we therefore have no guarantee that anything is “objectively” real. Source: Adimas / Adobe Stock.