The Family Feud Over Who Wrote ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas

“‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” is a cherished poem and storybook that perfectly capture the magic of Christmas. Children are bedazzled by the colorful imagery of sugar plums, flying reindeer and the jolly, twinkling-eyed Santa who whooshes down our chimneys. For the last two centuries, this festive poem has become as much of a staple at Christmas time as turkey dinners, presents and decorated trees. Each and every December, parents around the world would recite it verbatim. Few, however, realise that there is a debate going on as to who wrote ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas in the first place.

“‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” story book originated as a poem from the 1820s. Source: Andrews McMeel Publishing.

Publications of the Classic Christmas Poem

First Print 1823

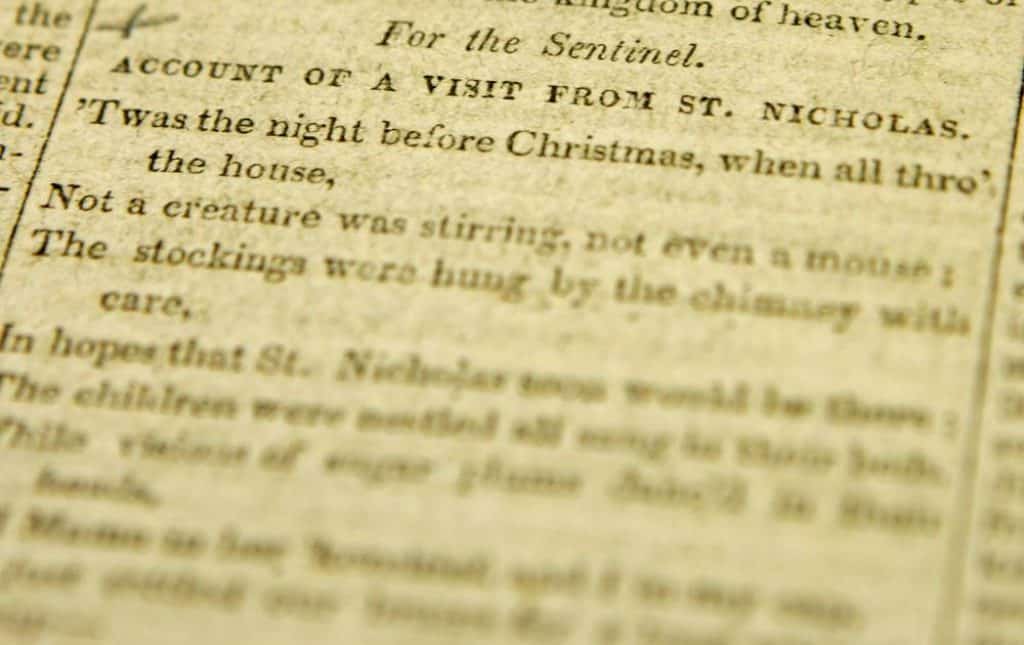

When it was originally published in the Troy Sentinel of New York, two days before Christmas in 1823, editor, Orville Holley, admitted in print the following:

We know not to whom we are indebted for the following description of that unwearied patron of music—that homely and delightful personage of parental kindness, Santa Claus, his costumes, and his equipage, as he goes about visiting the firesides of this happy land, laden with Christmas bounties; but from whomsoever it may have come, we give thanks for it. There is, to our apprehension, a spirit of cordial goodness in it, a playfulness of fancy and a benevolent alacrity to enter into the feelings and promote the simple pleasures of children which are altogether charming.

We hope our little patrons, both lads and lassies, will accept it as a proof of our unfeigned good will towards them—as a token of our warmest wish that they may have many a Merry Christmas; that they may long retain their beautiful relish for those unbought homebred joys which derive their flavor from filial piety and fraternal love, and which they may be assured are the least alloyed that time can furnish them; and that they may never part with that simplicity of character which is their own fairest ornament and for the sake of which they have been pronounced by Authority which none can gainsay, types of such of us as shall inherit the kingdom of heaven.

Clement Clarke Moore 1844 Book of Poems

The verse took up an entire column in print and the header read “An Account from a Visit of St Nicholas”. From these humble beginnings, a legend emerged and thrived over the following years. There is only Holley’s word that someone sent this missive in anonymously. It is quite possible that either he or one of his staff wrote it but preferred not to declare it for whatever reason.

Original printing of “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” in the Troy Sentinel. Source: NBC News.

The Christmas poem surfaced in newspapers another couple of times in the following 6 or 7 years. Then it disappeared out of the public domain until sometime in 1844, when a New York publisher, Bartlett, and Welford, released a book of poetry that Clement Clarke Moore authored. In it was a version of the now fabled classic. In a substantial preface, Moore revealed that he wrote the collections of poems at various points during his lifetime. Many people consider this to be an example of ‘case-closed’, and they do not consider that perhaps history might be wrong. In the same preface, Moore did go into detail in regards to lighter aspects to life in general. Descriptions of Moore indicate that he was somewhat stern and humorless or, at the very least, his reputation was usually more of a serious one.

How Did the Sentinel Get the Poem in 1823?

The story of how the “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” poem surfaced in the Sentinel is also open to some interpretation. The most common theory is that the eldest daughter of Reverend Doctor David Butler, Harriet, overheard the poem when visiting the Moores in 1822. She copied it to her own album and eventually sent it on to the Sentinel. Historians believe that Moore opted not to contest this publication, as he considered it beneath the dignity of a theological professor. This may or may not be accurate. There were no hints to even suggest links at a possible author.

Related: 11 Things You Didn’t Know About Christmas

For the rest of his life, which ended on 10 July 1862, Moore didn’t show any interest in the possible celebrity from the work he allegedly wrote. Not long before his passing, the New York Historical Society sent a representative to interview the 83 year old. The interview went unpublished for 47 years until January 1919. It offered little to no additional information about the poem. That is not such a bad thing though.

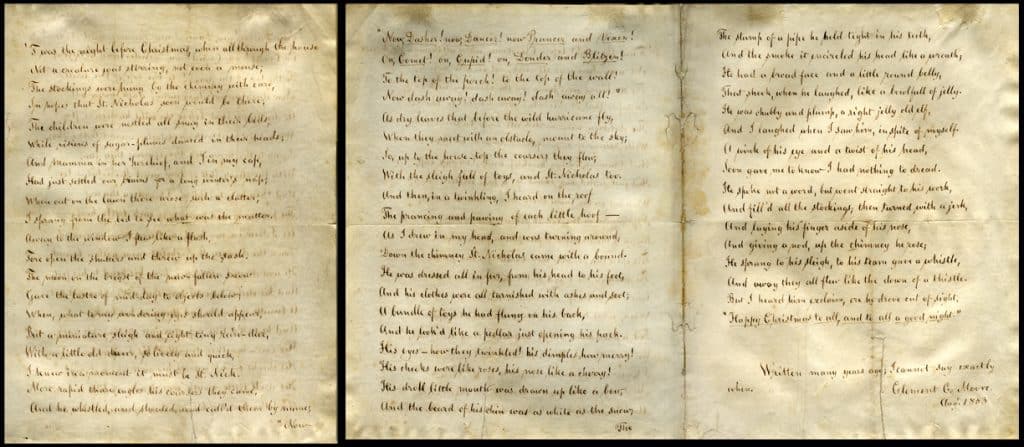

Clement C. Moore’s handwritten, signed copy of “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” 1860. Source: Heritage Auctions.

Moore didn’t confirm giving Harriet a personal copy, which could mean she did overhear it innocently enough. Moore also thought it was possible that Harriet obtained a copy by other means – perhaps via one of his female relatives. Dr. Moore had three children, two daughters sandwiching a son. It is logical to assume that the eldest girl may have shown more of an interest in Santa Claus than his other children since at the time of publication they both would have been a little too young to have piqued their curiosity.

The Missing Manuscript

Another fact that doesn’t work in the Moores’ favor is that the original manuscript is not in their possession. Also, there is no evidence that the original draft survived into modern times. Casimir Moore, Clement’s grandson, has gone on record with the firm belief that the intention for the poem was strictly for the benefit and enjoyment of Moore’s immediate family: not for it to become the world’s most famous Christmas poem that it has become today. Several claims at the authorship eventually compelled Clement to admit to it himself. Casimir also revealed that he had no knowledge of where the original manuscript could be today.

Assuming that Clement Clarke Moore didn’t pen the famous poem, then who else could have written the following?

“‘Twas the Night Before Christmas”

‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

The children were nestled all snug in their beds,

While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads;

And mamma in her ‘kerchief, and I in my cap,

Had just settled down for a long winter’s nap,

When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from the bed to see what was the matter.

Away to the window I flew like a flash,

Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash.

The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow

Gave the lustre of mid-day to objects below,

When, what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny reindeer,

With a little old driver, so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick.

More rapid than eagles his coursers they came,

And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name;

“Now, DASHER! now, DANCER! now, PRANCER and VIXEN!

On, COMET! on CUPID! on, DONDER and BLITZEN!

To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall!

Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!”

As dry leaves that before the wild hurricane fly,

When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky,

So up to the house-top the coursers they flew,

With the sleigh full of toys, and St. Nicholas too.

And then, in a twinkling, I heard on the roof

The prancing and pawing of each little hoof.

As I drew in my hand, and was turning around,

Down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound.

He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot;

A bundle of toys he had flung on his back,

And he looked like a peddler just opening his pack.

His eyes — how they twinkled! his dimples how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard of his chin was as white as the snow;

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath;

He had a broad face and a little round belly,

That shook, when he laughed like a bowlful of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,

And I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself;

A wink of his eye and a twist of his head,

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread;

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose;

He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew like the down of a thistle.

But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight,

“HAPPY CHRISTMAS TO ALL, AND TO ALL A GOOD-NIGHT!”

The Livingston Dutch Proof?

Perhaps the family of Major Henry Livingston Jr. might have an idea. According to them, reading the “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” poem was a private family practice they shared. They also insist that the first time this family tradition occurred was on or around 1830. Henry Livingston had Dutch ancestry, as his mother hailed from the Netherlands. A good number of references used in the poem itself do point to European origins, in particular, Holland. At least some of the reindeer have their names lifted from the Dutch language. Donner and Blitzen may reflect Dunder and Blixem – the Dutch words for Thunder and Lightning respectively.

Perhaps more conclusive evidence comes in ear-witness testimony. Four of Livingston’s own children, as well as a next door neighbour, insisted that the tale was often told to them from as early as 1807. Each even went as far to claim that there was a written copy with amendments and notations on it. However, their home burnt down in a fire, which took this possible blockbuster proof with it.

An academic study conducted on both men and their poetry came to the conclusion that it was almost certainly not possible that Clement Moore could have authored the work. Both the content and the structure were different from the prose used by Moore. It matched up much better with Livingston’s style.

After almost two centuries though, does it really matter? Just enjoy it for what it is: a brilliant poem that conveys the true spirit of Christmas.

Sources:

Mental Floss

Victoriana

Pulled 6 December 2016