In Norse mythology and religion, Odin, the king of all the Norse gods, rules the magnificent place in the spirit world called Valhalla. Along with his helpful Valkyries, Odin determines which warriors will die in battle and proceed to Valhalla after death. Once there, the warriors have a critical job. They must prepare for Ragnarok, the great battle during which the Giants will destroy the cosmos. Although this sounds like a fanciful plot for the movies, the Vikings and other people of the North took their beliefs about Valhalla very seriously. Exactly what is Valhalla in Norse Mythology, and what do the Old Norse sources tell us about the magical place?

Where is Valhalla?

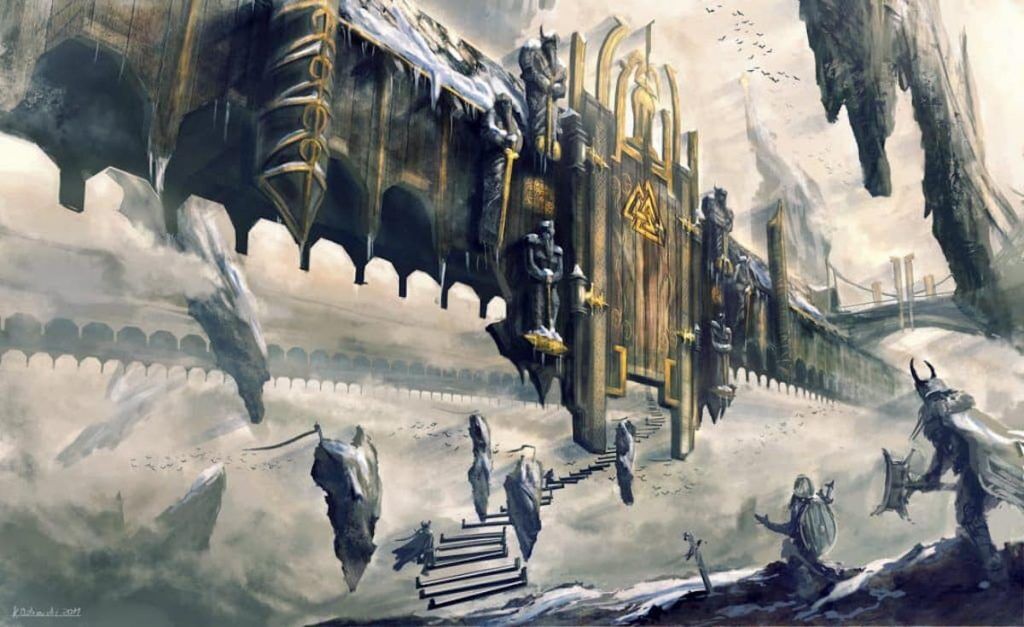

Pronounced val-HALL-uh, the word derives from Old Norse Valhöll, which means “hall of the slain.” The most common depiction of Valhalla places it in the splendid realm of the gods, Asgard – one of the nine worlds of the Norse cosmos. The world of Asgard is a place of beauty, order, and justice, and it is cradled within the bright upper branches of the world tree, Yggdrasil. Within the gods’ realm, Odin’s Hall of the Slain exists in a place called Gladsheim or “Happy Home.” This is also Odin’s favorite home in Asgard. Additionally, according to later Old Norse sources, Gladsheim is also the meeting place of the gods where they hold council each day.

However, as was the case for other Norse spirit worlds, some of the mythology also portrayed the Hall of the Slain as existing in an underground world.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Brian McCoy”]The very name Valhöll, “the hall of the fallen,” clearly seems related to the name Valhallr, “the rock of the fallen,” a title given to certain rocks and hills where the dead were thought to dwell in southern Sweden, one of the greatest historical centers of the worship of Odin.[/blockquote]

What Was the Afterlife Like in the Hall of the Slain?

The Valkyries, “choosers of the slain,” are beautiful warrior-maidens who assist Odin in a number of ways. Their most important job is to help determine which warriors live or die in battle. Of those who die, the Valkyries will usher half to Valhalla and they will become Einherjar (pronounced “ane-HAIR-yar”), Odin’s elite warriors. These honored fighters are destined to assist Odin in Ragnarok, the great final battle that will come at the end of the cosmic cycle during which most of all living things within the cosmos will die.

Related: Yggdrasil Tree of Life and the Nine Worlds of Norse Mythology

Meanwhile, the Einherjar spend most of their days honing their skills, fighting, and preparing for the great battle. The rest of their time they merrily feast from an endless bounty of all the best foods and drinks. The gods’ cook sacrifices the beast Saehrimnir each day to provide the finest meat. Thereafter, the animal comes back to life for the Einherjar to eat again the next day. Likewise, the goat Heidrun possesses magic udders that continuously produce the mead that the beautiful Valkyries serve to the warriors.

In the same way that the food and drink have abilities of rejuvenation, so too do the Einherjar. The injuries they suffer in their daily battles magically heal up in the evening, just in time for the feast. If they die, they come back to life.

It is an afterlife fit for kings and a place that any Viking would have aspired to enter.

Old Norse References to Odin’s Hall

The main sources of Old Norse mythology and religion stem from two compilations of sagas and poems. These are the Poetic Edda, also known as the Elder Edda, and the Prose Edda, also known as the Younger Edda. The Poetic Edda consists of various poems and was compiled in the 13th century by an unknown person. Likewise, the authors of the poems in the Poetic Edda are a mystery as well. However, many scholars agree that most of the contents originate from pre-Christian Old Norse traditions. The Poetic Edda provides the oldest descriptions of the Hall of the Slain.

You May Also Like: Sleipnir: Eight Legged Horse of Odin

The Prose Edda also derives from the 13th century and is the work of the Christian politician, historian, and poet, Snorri Sturluson. This Edda contains sagas, mythology, and treatises on poetry in the form of both prose and verse. Although Snorri extracted many concepts in the Prose Edda from Old Norse songs and poems, most scholars agree that he also interjected Christian concepts into the mythology. Additionally, where there may have been voids in the imagery or organization of concepts, he embellished rather wildly. Nonetheless, the Prose Edda is a very valuable source of Norse mythology, noteworthy heroes, and historic battles.

How Did Valhalla Look?

Grímnismál, “The Sayings of Grimnir,” is one of the Old Norse poems in the Poetic Edda. It was probably composed in the 10th century and provides the most common description of Odin’s Hall. According to Grímnismál, the hall shimmers with golden towers. Its roof consists of battle shields, and spears serve as the rafters. Armor covers the long benches. An eagle flies above the golden hall, while a wolf hangs above the western gates (some sources suggest the animals were symbolic carvings).

The branches of the tree, Laerad, presumed to be the same as the world tree Yggdrasil, hang above the golden hall. Heidrun the goat and Eikthyrnir the stag eat the branches of the tree. Surrounding Odin’s Hall the river Thund (“The Swollen” or “The Roaring”) roars loudly, and there is a sacred and ancient gate called Valgrind (“The Death Gate”) on the outer perimeter of the hall. Inside the gate, there are 540 enormous holy doors, and through each door, eight hundred soldiers will exit to fight the beastly wolf, Fenrir, in the battle of Ragnarok.

The following is an excerpt from Grimnismál :

8. The fifth is Glathsheim, | and gold-bright there

Stands Valhall stretching wide;

And there does Othin [Odin] | each day choose

The men who have fallen in fight.

9. Easy is it to know | for him who to Othin

Comes and beholds the hall;

Its rafters are spears, | with shields is it roofed,

On its benches are breastplates strewn.

10. Easy is it to know | for him who to Othin

Comes and beholds the hall;

There hangs a wolf | by the western door,

And o’er it an eagle hovers.

Other Mentions of the Hall

Eiríksmál is a skaldic poem anonymously composed during the second half of the 10th century. It honors the slain warrior and king, Eric Bloodaxe, and provides the first known mention of Valhalla (c. 885-954). Eric’s widow and queen, Gunnhild, commissioned this poem in which Odin prepares for the arrival of Eric and the other kings/heroes at his golden hall:

“‘What’s that dream?’ said Odin

I thought that before day rose

to clear Valhalla for the coming of slain men.

I woke the einherjar

told them to rise quickly

for benches to be strewn

dishes to be washed

I bade the Valkyries to bring the wine

for the great kings will be coming.”

Additional Old Norse sources that mention Valhalla:

- Völuspá, from the Poetic Edda, author unknown. A few brief mentions of Odin’s Hall.

- Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, from the Poetic Edda, author unknown. In stanza 38, Helgi Hundinsbane dies and goes to the Hall of the Slain.

- Hyndluljóð, from Flateyjarbok, a compilation from circa 1400, author unknown. Stanza 1 refers to Odin’s Hall as a sacred hall.

- Skáldskaparmál, from the Prose Edda, author Snorri Sturluson. Several mentions of Odin’s Hall.

- Gylfaginning, from the Prose Edda, author Snorri Sturluson. Here, the prose story of Gangleri takes place in Odin’s Hall.

- Heimskringla, author Snorri Sturluson. This provides a simple description of the golden hall as a place where the dead will arrive with their possessions in the afterlife.

How Did a Warrior Get Into Odin’s Golden Hall?

As noted, Odin and his Valkyries select half of the dead Viking warriors to go to Valhalla. The other half go to the afterworld of Folkvang, “field of the people,” or “field of the army.” Odin’s wife, Freya, rules over Folkvang. According to Daniel McCoy, author of The Viking Spirit, there is nothing in the extant pre-Christian Norse sources that highlights exactly what the selection process was for entry into Odin’s Hall. Therefore, just how or why Odin and his Valkyries chose certain people and not others is not explicit. It appears that the Norse afterlife was simply a continuation of this one and that Norse religion did not assign people to certain places in the afterlife based on moral merit or lack thereof, such as in the concepts of heaven and hell in Christianity.

It wasn’t until the 13th century, hundreds of years after Christianity had taken root in Iceland, that Snorri Sturluson filled in the conceptual gaps within Norse mythology using colorful embellishments. Additionally, Christianity influenced parts of the imagery that he added – some of which had nothing to do with the ancient Norse religion. Quoting McCoy, “According to Snorri, those who die in battle are taken to Odin’s Hall, while those who die of sickness or old age find themselves in Hel, the underworld, after their departure from the land of the living.”

It is logical, however, that Odin would have picked the crème de la crème of the warriors to join him in Valhalla to prepare for Ragnarok.

What Did it Mean to the Vikings?

Today when we hear or read about Norse mythology, we think of the stories like fanciful fairy tales: the imaginative stuff of books and movies designed to entertain us. However, for the Germanic and Norse people, their religious beliefs and pantheon of gods had a pervasive bearing on their everyday lives. For them, the gods truly existed.

As such, the Vikings tried to do what was necessary to appease the gods with their actions. For example, they held regular rituals on a private and community basis. They made sacrifices in exchange for specific divine blessings such as fertility, a bountiful harvest, or a successful battle. Additionally, they worshipped the animating spirits/gods in nature, such as rocks, mountains, and water sources.

For the Viking warrior, Odin’s Hall may have been foremost in his mind during every encounter on the battlefield. Perhaps their beliefs about Valhalla were the reason why the Vikings were among the bravest and fiercest warriors in history. Their battles in this life may have been merely a tryout for the elite army in the afterlife.

Therefore, one might surmise that the Vikings’ beliefs resulted in fighters who trained and fought without reservation or fear of death, as Odin may have been waiting just beyond the veil to honor them into his spirit world. If they could prove themselves, perhaps the king of the gods would select them to live out the last days of the cosmos like brave and honored kings in preparation for the final battle of Ragnarok.

References:

Norse Mythology for Smart People

Voluspa