The Soviet Union was well known for its propaganda and the widespread claims of success (often exaggerated) the country was experiencing. The Iron Curtain had been drawn, separating the Eastern bloc Soviet countries from the rest of the world, and much of what Russia was doing and creating was a mystery to many other countries, including the US.

One piece of propaganda boasted of the fantastic advancements the Soviet Union was experiencing regarding science and medicine. The propaganda included a TIME magazine article, pictures, and videos of one surgeon and his two-headed subject.

At first, the footage and photos looked like the worst version of early attempts at photoshopping, but this was not the case. Vladimir Demikhov had created a two-headed dog that had not only survived the horrific process but could respond to stimuli, drank water, and move about the lab.

Vladimir Demikhov did create more than one two-headed dog that lived for up to several weeks. The two-headed dog experiments overshadowed Demikhov’s incredibly successful surgical career, resulting in his death in obscurity in the late 1990s. Who was Vladimir Demikhov, and what was up with the crazy two-headed dogs?

Vladimir Petrovich Demikhov

Vladimir Demikhov was born on July 31, 1916, to a poor family of peasants in what is now known as the Novonikolayevsky district in Volgograd, Russia. His father was killed in the Russian Civil War, so his mother raised Vladimir, his brother, and his sister on her own.

She wanted her children to be well educated and ensured all three Demikhov children could attend good schools and colleges. As a teenager, Vladimir Demikhov became interested in the circulatory systems of mammals.

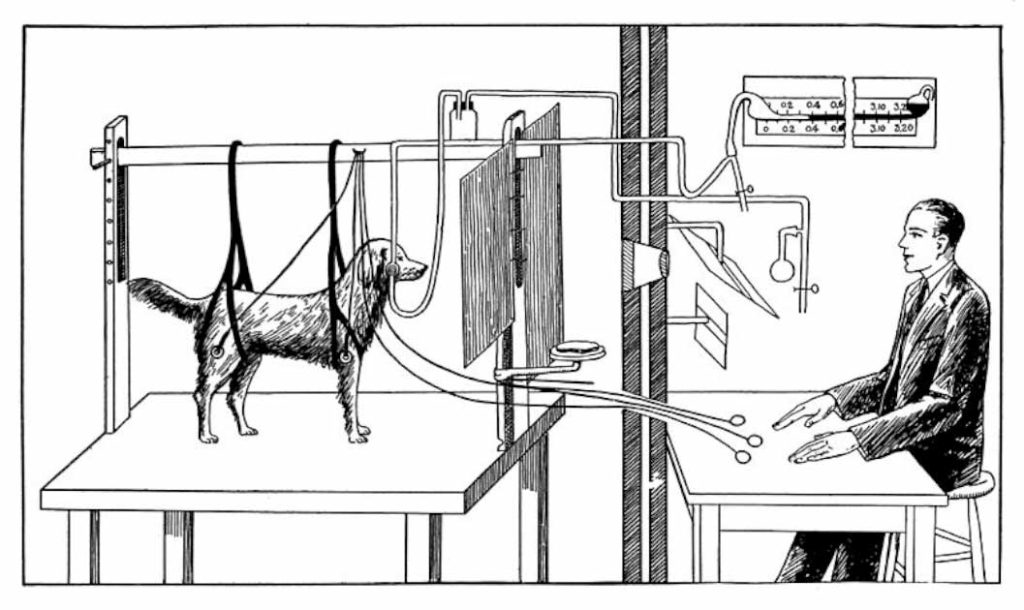

He wasn’t a psychopath; he found Ivan Pavlov’s theory of classical conditioning experience in dogs endlessly fascinating. His experiments may seem brutal but they were in pursuit of scientific understanding, not cruelty. Not that this offered any comfort to the dogs.

Vladimir Demikhov attended college at Voronezh State University in 1934, then transferred to Moscow State University, where he remained until graduating in 1940. While at Moscow State, Vladimir Demikhov experienced the first of many medical successes which changed the field of transplantology (a word Demikhov coined).

The first of Vladimir Demikhov’s creations was the world’s first artificial heart, and he performed the first artificial heart implantation into a dog. The dog lived two hours after the procedure, proving the viability of his approach.

From a scientific standpoint, the experiment was seen as a success. After taking a break from his experimentations to serve in World War II, Demikhov returned to Moscow State University and dove head-first (no pun intended) into his experimental research.

A Scientist Above All

Most of Vladimir Demikhov’s contributions to science were not recognized when he was alive due to the controversial two-headed dog experiment, which destroyed his reputation. Vladimir Demikhov was however a pioneer, responsible for many of the first surgical procedures we find today.

In 1946 he performed the first intrathoracic heterotopic heart transplant, which means he successfully performed a transplant of a heart into the chest cavity, which was unheard of at the time. 1946 was a big year for Vladimir Demikhov, and he also performed the first heart-lung transplant in a mammal.

These groundbreaking medical procedures continued, and Vladimir Demikhov was also responsible for the first liver transplant, and the first orthotopic heart transplant. The orthotopic transplant meant that a living heart was transplanted into another mammal in the correct position where the heart belonged. Before that surgery, all heart transplants were positioned in the neck of the receiver to connect the new organ with the veins of the neck.

In 1952 Vladimir Demikhov performed the first mammary-coronary anastomosis, which involves creating a surgical connection between two body structures to carry fluid. An example of anastomosis we see today happens after a section of a person’s colon is removed due to cancer and is reconnected to restore the bowels’ regular movements.

One year later, Vladimir Demikhov performed the first successful coronary artery bypass surgery. Between 1963 and 1965, he created the world’s first collection of living human organs available for surgical use or, simply put, the world’s first organ bank.

Vladimir Demikhhov’s experiments were so significant because he would work with “live organs.” These organs would be kept alive with a hand pump, like how lung transplants are kept on a machine to keep them inflating and deflating before it enters the recipient’s body in today’s medicine.

Previously, people attempted to perform transplants or reconnect an organ placed into a hypothermic state to preserve it when outside the donor’s body. The live organs Vladimir Demikhov used were more successful in their ability to resume regular function in a new host body.

The animal used as the experiment subject could live for hours or days after the surgery. Then he performed the first head transplant in 1954.

The Two-Headed Dog Experiments

Let’s address the dog thing right away. Vladimir Demikhov did not hate dogs or hunt them for his mad scientist experiments. Back then, and even today, Moscow has upwards of 50,000 stray dogs roaming the streets.

The dogs have learned how to board the Metro trains to travel from one location to another, and nobody minds the four-legged strangers. Neutering and spaying dogs wasn’t a common practice, and the stray dog population exploded in the city at an alarmingly fast rate.

As upsetting as it is, dogs were used extensively as scientific and medical subjects because so many were present and accessible. Many western countries continue to rely on animal testing to this day, although none apparently go down the “what if more heads?” route.

The two-headed dog experiment was not some sick attempt to create a breedable two-headed dog, nor was it created to make a monster or cause animal suffering. The two-headed dog experiments aimed to see if two living creatures could be connected to each other and survive using only one of the dog’s circulatory systems.

- Weird Science! What was James Graham Doing in His Electric Sex Temple?

- Andrew Crosse Created Life In A Lab

This was a pioneering thought process, the precursor to such procedures today as human ears grown on the backs of mice, using their circulatory system until they are ready to be transplanted to their subject. Whether such approaches could even work was unknown to Demikhov, and it would seem that his scientific curiosity got the better of him.

The issue with these head transplant experiments was that these experiments had no real-life applications like all his previous transplant experiments on dogs. People needed organ transplants to sustain or prolong their lives. Nobody needed a head transplant, let alone a two-headed dog. Add to that the questionable ethical and moral issues, and this research was problematic at best.

Vladimir Demikhov was not the first surgeon to attempt to create a two-headed dog. In 1908 French surgeon Dr. Alexis Carrel and his partner, Dr. Charles Guthrie, an American physiologist, performed the same experiment that Vladimir Demikhov would attempt forty years later.

The two men managed to create a two-headed dog that seemed like a successful operation, but the animals degraded rapidly and were euthanized after several hours of declining health. Vladimir Demikhov’s two-headed dog in the now infamous video was not the first one he attempted to create, rather the 23rd, 24th, or 25th time the experiment took place (records vary greatly concerning how many times the experiment was repeated, but the consensus was over 22 times).

For the experiment recorded by the media, Vladimir Demikhov chose a smaller dog named Shavka and a large stray German Shepherd named Brodyaga (the Russian word for ‘tramp’). Brodyaga was to be the host dog, and Shavka was to be the secondary head and neck.

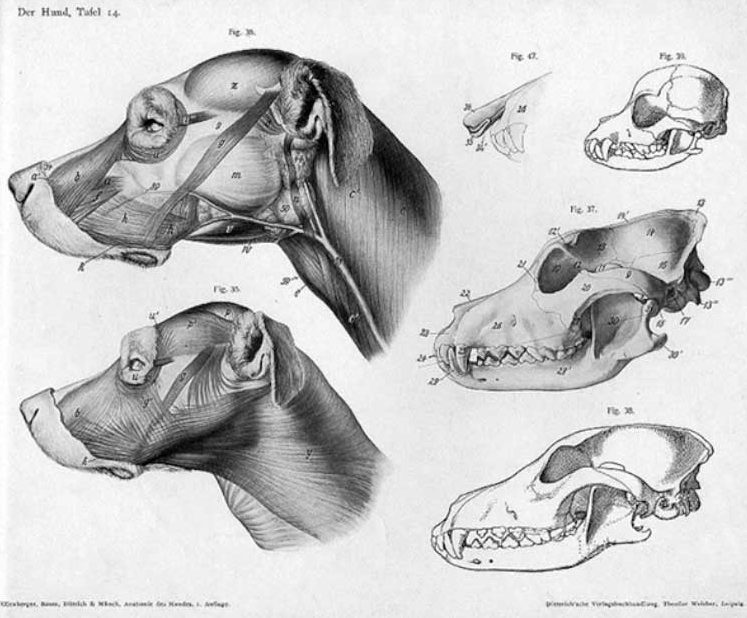

Shavka’s lower body was amputated but retained her own lungs and heart that remained connected until seconds before the transplant. Shavka’s head and two front legs were then attached with an incision on Brodyaga’s neck, and vascular reconstruction was performed to allow the heads to share a circulatory system.

The last step was securing the dogs at the vertebrae using plastic string. The procedure took three and a half hours from start to finish, and both heads could hear, see, smell, and swallow. Shavka was not attached to Brodyaga’s stomach in any way, so whatever she drank would pour out of her via an external tube. Shavka and Brodyaga survived four days and the cause of death was determined to be a vein in their shared neck which was damaged during the procedure.

The longest living of Vladimir Demikhov’s two-headed dogs survived 38 (though some reports list 28 or 29 days) days in 1968. After it died, the bodies were taxidermied and gifted to The Museum of History of Medicine in Riga.

The dog was previously on tour in Germany from 2011-2013 but has returned to Riga, where you can see it on display today. Once the news of Vladimir Demikhov’s two-headed dog procedures spread globally, many doctors came to the Soviet Union to learn about the surgical techniques Vladimir Demikhov and other Soviet surgeons had developed.

American doctors came to learn from Demikhov, and by 1962, the general consensus of the U.S medical community was that the two-headed dogs were not nonsense but something that showed the promise of the success of live organ transplantation. Vladimir Demikhov died at 82 from an aneurysm on November 22, 1998, in obscurity on the outskirts of Moscow.

Top Image: The last two headed dog transplant performed by Vladimir Demikhov in 1959 in east Germany. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-61478-0004 / CC BY-SA 3.0 de.

By Lauren Dillon