Archaeologists have discovered evidence of what could be the world’s oldest dwelling. Humans lived in the ancient Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa as early as two million years ago, according to some recent research.

The Wonderwerk Cave was first discovered in the 1940s and has piqued the interest of scientists all over the world ever since. Previous research into the cave’s depths and works of art on its walls has centered on the crystals discovered there.

Professor Ron Shaar, a researcher at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Institute of Earth Sciences is confident in saying that our human ancestors were manufacturing primitive stone tools inside Wonderwerk Cave as early as 1.8 million years ago.

A Very Early Start for Civilization

Wonderwerk Cave is an archaeological site in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa, developed originally from holes eroded naturally from the dolomite rocks of the Kuruman Hills, located between Danielskuil and Kuruman.

Hillside erosion first uncovered the northern end of the hollow, which stretches horizontally for around 140 meters (460 feet) into the hill’s base. Natural sedimentation processes such as water and wind deposition, as well as the actions of animals, birds, and human predecessors, have accumulated sediments inside the cave up to 7m (23 ft) in depth.

Much digging to do, then, and archaeologists have indeed been studying and excavating the site since the 1940s. Their findings provide crucial insights into the dawn of human history in the Southern African subcontinent.

- The Mystery of Cave Paintings: Early Animation?

- Who Guards the Wookey Hole Caves? The Legend of the Wookey Hole Witch

Much of what is found suggests these caves are the prototype for human civilization in the region, which has far-reaching consequences. For example, what is thought to be the oldest controlled fire has been discovered at the Wonderwerk Cave.

Layers of Archaeology

The cave has archaeological deposits dating from the Early, Middle, and Later Stone Ages, right through almost to the present day, all layered up in 6 m (20 ft) of accumulated sediment. Basal material entered the cave about 2 million years ago, according to cosmogenic dating.

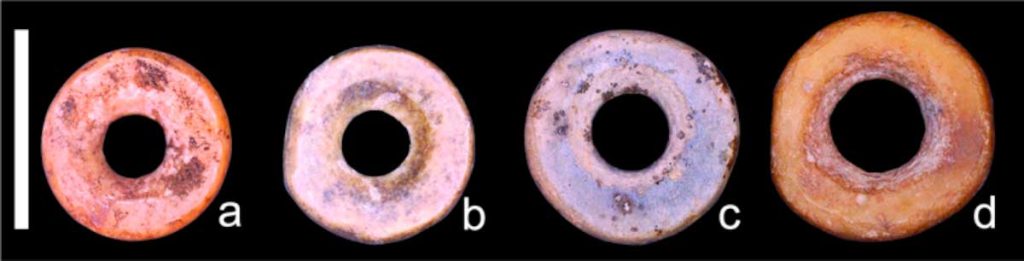

It is only much later that the sophisticated findings in the cave emerge, to be sure. Small engraved stones found within the deposit, primarily from the Later Stone Age sequence, date back approximately 10,500 years, and paintings within the first 40 m (130 ft) from the entrance are likely all less than 1000 years old. The links between previously etched or striated objects have yet to be proven.

Malan, Cooke, and Well’s early archaeological studies from the 1940s were briefly followed up by K.W. Butzer in the 1970s. Between 1978 and 1993, more substantial excavations at the site were carried out by Peter Beaumont of the McGregor Museum in Kimberley. Anne Thackeray and Francis Thackeray working at the site in 1979, excavating and investigating the Later Stone Age layers from cultural and archaeozoological perspectives.

From around 2008, Michael Chazan of the University of Toronto, Liora Kolska Horwitz of The Hebrew University, and Francesco Berna of Simon Fraser University collaborated with the McGregor Museum (where excavated assemblages are housed) on a project led by Michael Chazan of the University of Toronto, Liora Kolska Horwitz of The Hebrew University, and Francesco Berna of Simon Fraser University. As part of the ZamaniProject, a digital model of the site was built using laser scanning.

The findings of these archaeological, dating, sedimentological, and palaeoenvironmental investigations were initially presented at a conference held at the site by Chazan and Horwitz. They’ve since been published in several publications, as well as in a special issue on the site in 2015. The results of magnetostratigraphy and cosmogenic dating of the cave were announced in April 2021 by archaeologists from the University of Toronto and the Hebrew University.

- Herto Man: The Oldest Humans, or the Missing Link?

- God and the Dawn of Man: Did Homo Erectus have its Own Religion?

In 1993, on the basis of these excavations Wonderwerk Cave was designated as a South African National Monument. The cave was opened for the public as a site museum in the same year.

What was the Cave Used For?

It was an entirely practical consideration which revealed the archaeology hidden in the cave system. Local farmers dug up large sections of the cave interior in the 1940s to bag and sell organic-rich material as fertilizer, which included stratified archaeological deposits containing artifacts, bone, and other material.

These finds would have been crucial to understanding the site’s cultural and palaeo-environmental history, but the archaeology was lost when the bones were dug up. The discovery of bone led to the beginning of archaeological and zooarchaeological investigations.

One thing archaeologist agree on is evidence of the deliberate use of fire by the prehistoric ancestors around 1 million years ago, in a layer deep inside the cave, by effectively establishing the transition from Oldowan artifacts (primarily sharp flakes and chopping tools) to early handaxes. The latter is particularly significant because other early indications of fire use come from open-air places where wildfires cannot be ruled out.

Wonderwerk also has a variety of fire relics, including burnt bone, silt, and tools, as well as ash. It seems that once the inhabitants of the cave system discovered the secret to fire, they were quick to recognize its uses.

Were these early Homo Sapiens who discovered fire here, or other human species? Much work is still to be done at Wonderwerk, and who knows what other secrets this “miraculous” cave system has to uncover.

Top Image: Evidence of the earliest controlled fire has been found at the Wonderwerk cave site. Source: Gorodenkoff / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri