The further we go back through history, the less clear things become. Fact slowly gives may to legend, and ultimately to myth.

Out of those transitions however come some tantalizing questions, characters who may be fictions born of the folklore and traditions of the region, or who may be very real. Figures like King Arthur, Milos Obilic, William Tell, or Robin Hood.

So it is with the story of Zheng He, where we are presented with a sister problem to those above. We know he was a real Chinese explorer and sailor, and we know much of the world of the early Ming Dynasty world that he lived in.

But, within this factual framework lie stories of enormous wooden ships and great treasure fleets, evidence for which has never been found. What about Zheng He is true, and what is mere embellishment?

Who was Zheng He?

Zheng He was born in 1371 in Kunyang, a town of Yunnan province during the early Ming dynasty of China. He was the descendant of a governor of the Yunnan province under the Mongol Empire at the time of the early Yuan dynasty.

Zhang was born in a Muslim family and has been named Ma He, with ‘Ma’ being the Chinese translation for ‘Muhammad’. Zhang He’s father, Ma Hajji had earned the title of “hajji” after making his pilgrimage to Mecca. He had one older brother and four sisters younger than him.

The popular lore of Zheng He started from the invasion of Yunnan by the Ming dynasty in 1381. Almost 10 years after his birth, the province of Yunnan was under attack, and He’s father, Ma Hajji died in the ensuing battle.

As he was escaping the heat of battle, the Ming armies captured Zheng. General Fu Youde took Zheng He as his prisoner, and this is where he was placed in the service of Prince of Yan, Zhu Di, who would later become the Yongle Emperor.

- Fireships in the Night: How was the Spanish Armada Defeated?

- Gasparilla: Was the Legendary Spanish Pirate Jose Gaspar Real?

This might seem a stroke of fortune considering what could have happened to a Muslim child captured by a Chinese army, but is wasn’t all roses for Zheng He. At some point over the next four years he was castrated, before being placed in service of the prince.

The other prominent highlight about Zheng, as outlined by historians, refers to his eclectic viewpoint on religion. According to the Changle and Liujiagang inscriptions, Zheng was an ardent devotee of Tianfei, the patron goddess for seafarers and sailors.

His devotion to the sea goddess was also long associated with the successes of the “Zheng He Fleet” on his popular expeditions. Zheng sought protection from the patron goddess of sailors as well as at the tombs of Muslims on Lingshan Hill.

A Fleet of Enormous Ships

During his time as a servant to the Prince of Yan, Zhu Di, Zheng He gained the trust of the prince and became a junior officer in the army, gaining skills in diplomacy and war. His palace position would benefit him in acquiring the skills needed to be useful to his prince.

In addition, Zheng also made some influential connections in court. He was also a part of the military campaigns of Zhu Di against the Mongols and also accompanied the prince on his first expedition.

Zheng had safeguarded the city reservoir Zhenglunba in the Siege of Beiping and also played a vital role in the siege of Nanjing, the imperial capital. The achievements of Zheng during the Jingnan Campaign earned him many accolades and respectable positions in court.

After claiming the throne, the Yongle administration restored the economy of China, which had been devastated by war. Now, the Ming court wanted to display their naval power to control the countries bordering the Indian Ocean.

The Chinese had been exerting their dominance over sea for around 300 years, with a focus on spices, aromatics and raw industrial materials. On top of it, maritime exploration also broadened the geographic awareness of the Chinese.

The Yongle Emperor not only adorned the court eunuch, Zheng He, with many important titles but also selected him for a series of nautical missions. For this purpose Zheng He was given a fleet consisting in the latest in Ming maritime thinking.

- The Legend of Miloš Obilić: Did He Assassinate a Sultan?

- England’s Great Outlaw, Robin Hood: Real or Legend?

Zheng set sail for the first time on his expeditions in 1405, and his fleet had around 62 ships carrying 27,800 men. Over the course of seven expeditions, Zheng He traveled to many countries and extended diplomatic relationships.

At the same time, the massive fleet commanded by Zheng on his first expedition is a subject of wonder. The fleet included treasure ships, equine ships, supply ships, troop transports and patrol boats alongside water tankers. On top of it, the fleets also carried navigators, workers, doctors, soldiers, sailors and explorers.

And, difficult as it is to believe, it seems this enormous fleet was a reality. Multiple accounts, from China and elsewhere, attest to the magnificence and sheer size of the ships, something the world had never seen. In less than 100 years Columbus would cross the Atlantic in three boats which look as mere dinghies next to Zheng He’s massive junkers.

What Happened to Them?

The massive fleet built by Zheng He and commissioned by the Yongle Emperor was decommissioned after the seventh voyage. The new emperor felt that the voyages were too speculative and had no purpose which justified the tremendous outfitting costs.

Upon the death of the Yongle previous emperor, Zheng was therefore ordered to assume post at Nanjing and disband his troops. However, the impact of the massive Zheng He Fleet lingered long in the memories of the seas it sailed.

Was it a peaceful envoy? Historical accounts suggest otherwise, as the troops had captured a ruler in Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) in 1411 and also established a colony in 1407. On top of it, the fleet had engaged in military conflict at multiple sites in Southeast Asia.

But Zheng He himself would never return to China, dying at sea as he guided the fleet home for the final time. After the death of Zheng He at sea during his final voyage, the expeditions were put to an end.

The fleet must have been disbanded, and you could find the only remnant of the tales of Zheng He’s expeditions in his empty tomb at Nanjing. However, the effect of the expeditions by Zheng could have provided an alternative past driven by cosmopolitanism rather than violent colonialism.

One of the most striking symbols of the end of the maritime fleets of China is evident in focus on the Great Wall. Upon the end of the massive expedition fleets or treasure fleets, the Chinese state moved away from the sea more inwards. The ships themselves were totally lost to time, and only the memory of China’s great moment of mercantile and diplomatic expansionism remains.

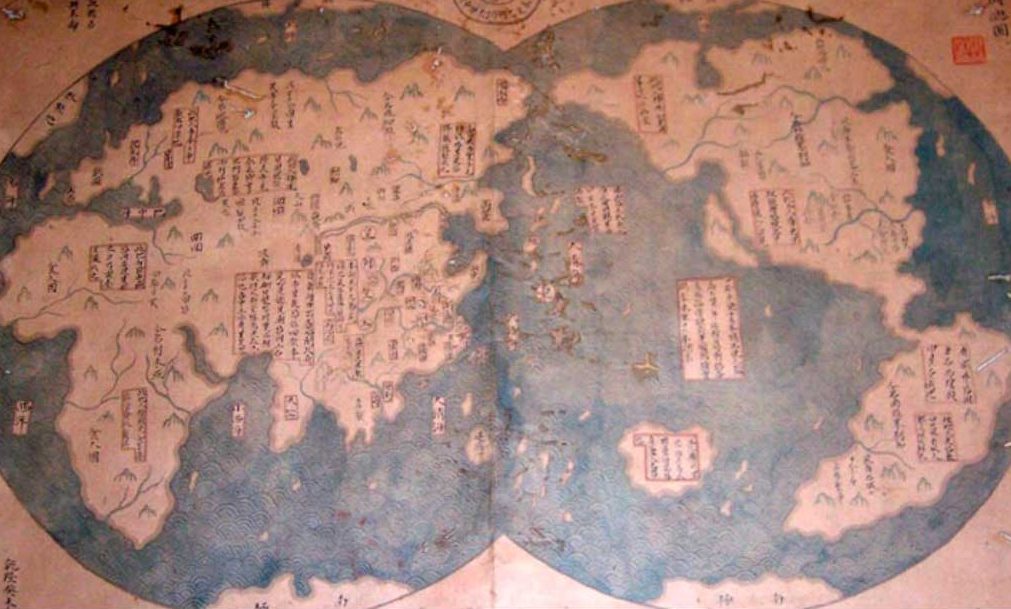

Top Image: The Fleet of Zheng He was said to include the largest wooden ships ever seen. Source: Kosov vladimir 09071967 / CC BY-SA 4.0.

By Bipin Dimri